SRI LANKA IN A NUTSHELL

LMD ARCHIVES (JULY 1996)

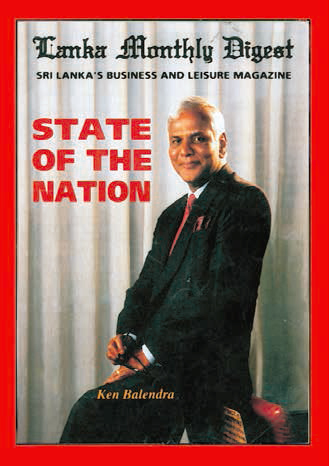

STATE OF THE NATION

According to Ken Balendra – Chairman of John Keells Holdings

The Sri Lankan economy is flagging and is obviously on a downturn. Much of the blame falls on myopic policy and political bungling, but there is also an intense war being fought in the north and east of the country. It is a war that has, over the past 13 years, taken its toll on the development of our nation. As the blood splattered shadow of terrorism shrouds the country, the dynamism infused by liberalised economic policies has been numbed by a lethargic wait-and-see attitude. Many investment decisions, Sri Lankan and foreign, are in abeyance – awaiting the dawn of a better tomorrow.

As clouds of gloom hang low over the corporate sphere, there are yet valiant companies who are willing to jump the hurdles and get ahead, when all about them are losing courage and focus. Ultimately, it is an issue of leadership and vision.

The LMD 50 – a ranking of the 50 leading listed companies in Sri Lanka, based on turnover – is a guide to leadership in Sri Lanka’s crisis-riddled corporate sector. John Keells Holdings (JKH) tops The LMD 50 for the second year.

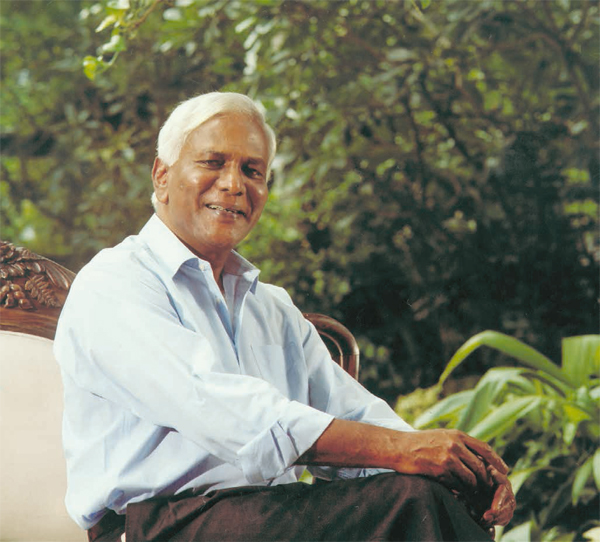

The Chairman of JKH, 55-year-old Ken Balendra, the first Sri Lankan chairman at John Keells, has steered the company’s fortunes over the past six years. Affable and courteous amidst the pressures of a hectic workday, Balendra, with a contemplative manner and reflective gaze, speaks his mind on the various issues that keep plaguing the Sri Lankan economy over and over again.

One of the economy’s greatest worries right now, he feels, is the billowing budget deficit with the government borrowing heavily from the public to fund the war. High interest rates are not helping the economy either, he says, for it is not profitable for investors to borrow at such unrealistic rates.

He feels that sometimes, we tend to labour under the misconception that investment means foreign investment only. “But the catalyst for foreign investment is local investment.” Therefore, it is necessary for local entrepreneurs to be given sufficient incentives to develop their various sectors.

As Balendra says, it is not that local entrepreneurs are unable to deliver the goods. The tourism industry, for instance, was developed almost entirely by local entrepreneurs.

Yet, the larger quantum of investment must necessarily come from outside the economy, as local investment is limited. Balendra notes: “Foreign investors diligently look to see what local investors are doing.” He says, if we hold back, then they too will hold back. And they can afford to do it. This is why John Keells is venturing ahead, in spite of the somewhat discouraging environment,as an equal partner with foreign collaborators.

Balendra feels that the private sector has been most successful in developing the port, which is the largest private sector venture undertaken in Sri Lanka. What is more, he says, all infrastructure projects should be handled by the private sector, “but the government must act as the facilitator.”

This view stems directly from Balendra’s opinion of a government’s place in business. He sees no need to split hairs on this issue: “Government, whichever party is in power, should not be in business.”

Furthermore, government should not interfere in an open market economy and should allow market forces to prevail.

He feels that when government begins to dabble in parochial issues, it loses track of the wood for the trees: “A government should focus on the overall macroeconomic situation.” Balendra emphasises the mixed signals sent out by the government, to the detriment of foreign investment. In his opinion, policy statements laid out by the present regime are heading in the right direction. The problem seems to be that the pace of implementation

has fallen below desired levels.

Another point that confuses the investor is the country’s approach to devaluation. Balendra feels that the central bank’s overconcern in curbing inflation, resulting in creeping devaluation, is self-defeating in the quest for foreign investment – in 1995, there was an eight percent depreciation of the rupee.

He believes that it is much better to have a steep devaluation, such as was imposed in India and Pakistan. South Korea went in for a massive devaluation and then kept its currency stable for some time. Otherwise, he asks, how can foreign investors judge the feasibility of projects?

This overemphasis on curbing inflation also has a negative impact on export oriented industries, for they are no longer competitive with the likes of India and Pakistan. Then again, to generate employment, one has to envisage investment. And as Balendra says, in a limited market like Sri Lanka – with a population of only 18 million – the majority of industries must necessarily be export oriented.

Nevertheless, Balendra is very much aware of the need to protect local manufacturers. He speaks of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) and the South Asian Preferential Trade Arrangement (SAPTA), which are being considered at government level in SAARC countries. His concern for Sri Lanka is that when signing the agreements, we need to be aware of the danger of becoming an import oriented country and consciously prevent the closure of local manufacturers.

The labour unrest and violence that have plagued the Sri Lankan economy in present times have, according to Balendra, had a very negative impact on investors, both here and abroad. He feels that this has come about through unrealistic expectations, following the change of government in 1994, and the misdirected focus of the Labour Department, which seems to be totally enmeshed in fighting for the rights of those already employed.

Balendra feels that the need of the hour is to generate more employment: “Item number one on the list of priorities should be the creation of employment.” The unemployment rate is more than 12 percent annually, with a

much higher percentage in the 20-30 age group. “Unemployment is the second biggest problem the country is facing right now,” he adds.

And Balendra feels the necessity for a planned and effective programme to educate workers, and the need to win the cooperation of the workforce and trade unions. “With the unemployment situation we have, I feel those who have jobs should consider themselves in a very privileged position,” he adds.

JKH’s Chairman also feels that the individual should decide how he or she wants to be paid: “I can see Sri Lanka moving towards a piecerate wage.” He says that unions must cooperate so that their members stand to benefit by way of an improved quality of life. He cites Malaysia, which has a strong and stable economic policy, and which has improved the quality of life of all its people.

Balendra says that any legislation, vis-à-vis the Workers’ Charter, should include not only the responsibilities cast on employees but also provide for the rights of employers who are risking their money.

Myopic steps like the controversial Workers’ Charter are what negate the impact of the government’s stated policy of promoting the private sector as the primary catalyst for growth.

According to Balendra, another factor causing concern to the corporate sector is the new Environment Act, which is still in the draft stage. He says: “We all want sustainable development but certain proposals need to be discussed further with the private sector so that the Act promotes sustainable development.”

He echoes the view of business leaders in the country, by saying: “One has got to walk the tightrope between development and the environment.”

He feels that Sri Lanka made a big mistake in shifting attention away from agriculture and onto manufacturing: “We need to take one step up from garment factories and into a larger framework where agro-based industry will be the backbone of the economy.” He believes that Thailand is streets ahead of Sri Lanka, and they are in the agro industry – from growing in the fields, right up to canning and bottling. We should have a combination of agriculture and manufacturing, he insists.

In agriculture itself, he believes, we should make the changes thought necessary by time. For instance, the marginal tea lands were planted over 100 years ago. But we don’t have to continue with the status quo. One advantage of privatising the plantations, according to Balendra, is that the new ownership has the opportunity to both rationalise and diversify. Talking of opportunity, there is the pertinent issue of education and employment expectations.

Balendra stresses that graduates emerging from universities need to understand that there is a limit to executive jobs and that not every graduate can expect to be an executive. Like in India, they need to understand that with the large numbers of graduates entering the job market each year, many of them would have to work at a supervisory level first.

It is Balendra’s personal view that a student who enters a Sri Lankan university after such intense competition, and then gets through with a first or second class, shows more potential than a student who gets into Oxford or Harvard.

To him, it is very unfortunate that Sri Lanka made a bad political move in deciding to neglect English as a link language – a problem now compounded by the dearth of good teachers of English.

If people who had never seen a diamond in their life can cut the stones to meet international standards, if people who had never handled computers in their lives can be trained to be equal to computer operators around the

world, then they can also learn English to be second to nobody… given the chance.

And this is exactly what Balendra has done at John Keells. He advertised in the Sinhala newspapers for 12 graduates. Job applications poured in from various parts of the country: 12 people were finally chosen. Balendra told his employees: “These 12 people may not know English but they are cleverer than you; so teach them English and absorb them into the team.” This was over two years ago. Those graduates have all fitted well into the organisation, absorbed its culture and learned the English language. This is why, says Balendra, we should not take a defeatist attitude and say we cannot expand because middle- level managers cannot be found: “I think there is an abundance of quality employees. It is only a question of getting hold of them, and training and moulding them.”

He says employee turnover at John Keells is very low mainly because of a high level of motivation:“We are a large family of people working as a team.” John Keells also seems to be giving women the chance to rise to senior management level, which is more than can be said for most of Sri Lanka’s corporate sector. There are women directors on the boards of seven of the listed Keells companies, and one on the main board.

Sri Lankans can be as good planners as anybody else in the world but they need to be given the chance and the motivation, says Balendra. “The decision-making process is not filtering down adequately in many instances.”

His advice to the corporate sector is: “Full delegation and responsibility, coupled with full accountability and answerability, will enable the management system to get the necessary feedback in the shortest possible time.”

All in all, Balendra feels Sri Lanka has not reached its potential to develop. Located so strategically, Sri Lanka can well be the hub of this region for financial services, shipping and aviation.

He feels that while fighting terrorism in the north and east, the government should, on a parallel level, focus on the economy – so we could actually meet force with force.

“If, by some good fortune, we can solve the north-east problem, then the sky is the limit for us.” With so much in our favour – geographical location; a high rate of literacy; flexibility of the people with a warmth and friendliness hard to match in other parts of the world – we can “sprint towards a Malaysian situation.”If we would only try.

Perhaps, this would not seem so arduous, if only this vision – and the leadership that goes with it – was more generously spread across the Sri Lankan economy, which is in the stranglehold of bureaucracy.