THE MEANING OF SUSTAIN+ABILITY

THE PENDULUM BETWEEN ‘ECO’LOGY AND ‘ECO’NOMY

BY Tameez Bohoran

Choosing our ‘eco’ has been quite the struggle lately especially in the local construction industry. It’s almost like going on a road trip to the hills.

Choosing our ‘eco’ has been quite the struggle lately especially in the local construction industry. It’s almost like going on a road trip to the hills.

Which route do you take? Do you take the faster, less congested route to get there? Or do you take a slower route where there’s possibly more of a blockage but you get to stop at your leisure for tea, top up your tank and wallet at the next town you drive by, and pause to take in the scenery – all while enjoying the journey you took to reach your destination?

As much as time efficiency is of utmost importance in reaching the target, in the grand scheme of things, we sometimes forget that the latter route gives us options, and the liberty to pause and choose how we want to experience the journey all while uplifting the lives of the simple roadside cashew cart or weaver.

Most often today, buildings are pitted in races against time and the construction world is in a constant battle between choosing to be economically versus ecologically conscious. And therein lies the most often overlooked aspect – being socially conscious.

Sustainability has been a more common term in the recent past, causing worldwide mayhem with governments, conglomerates and practices trying to find answers to how we can mitigate global resource depletion, make everything greener, offset the carbon footprints of projects, implement the three or five R process, how to harness renewable energy and so on.

But how did we all get here? Why are we asking these questions now? What is truly the meaning of sustainability?

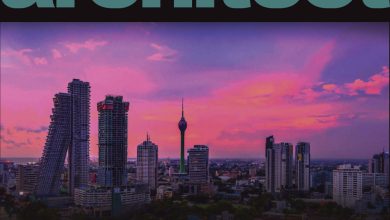

Many developed nations are starting to take action to fight the climate crisis, creating sustainable cities and implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out by the United Nations.

Larger practices in the world are making efforts to address the status quo as well by endorsing sustainability manifestos put forth by their governing bodies, and looking at alternative methods of construction, research and experimentation on material efficiency, and the need to reduce a project’s embodied and operational carbon.

What do you do after a building has reached its optimal lifespan? Do you demolish it? Do you retrofit it?

For example, MVRDV’s demountable office building – Matrix One – was designed to be deconstructed and used for parts after it reaches the end of its lifespan.

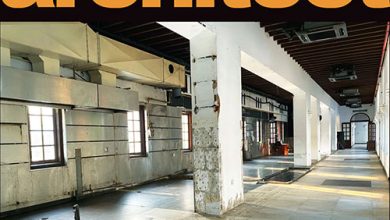

The argument against this would be why not try the alternate approach of adaptive reuse where a countless number of older buildings are being retrofitted for new purposes even in the local context? Or better yet, why not just make buildings that are timeless – such as century old buildings like Hagia Sophia with its functional versatility that has lasted the course of its lifespan over the past few centuries?

There is no linear solution to addressing the problem of sustainability but rather, it must be understood that every project has a specific need and context – whether it be the physical, social, ecological or even cultural context. It’s our responsibility to design a building that caters to and adds integrated value to that project specific context.

This holistic approach goes beyond merely adhering to local guidelines set in place for light and ventilation requirements, adding green terraces to reduce heat gain, increasing the use of renewable energy systems or choosing ecologically friendly building materials. It also needs to consider the social fabric and how buildings contribute to enhancing the quality of life.

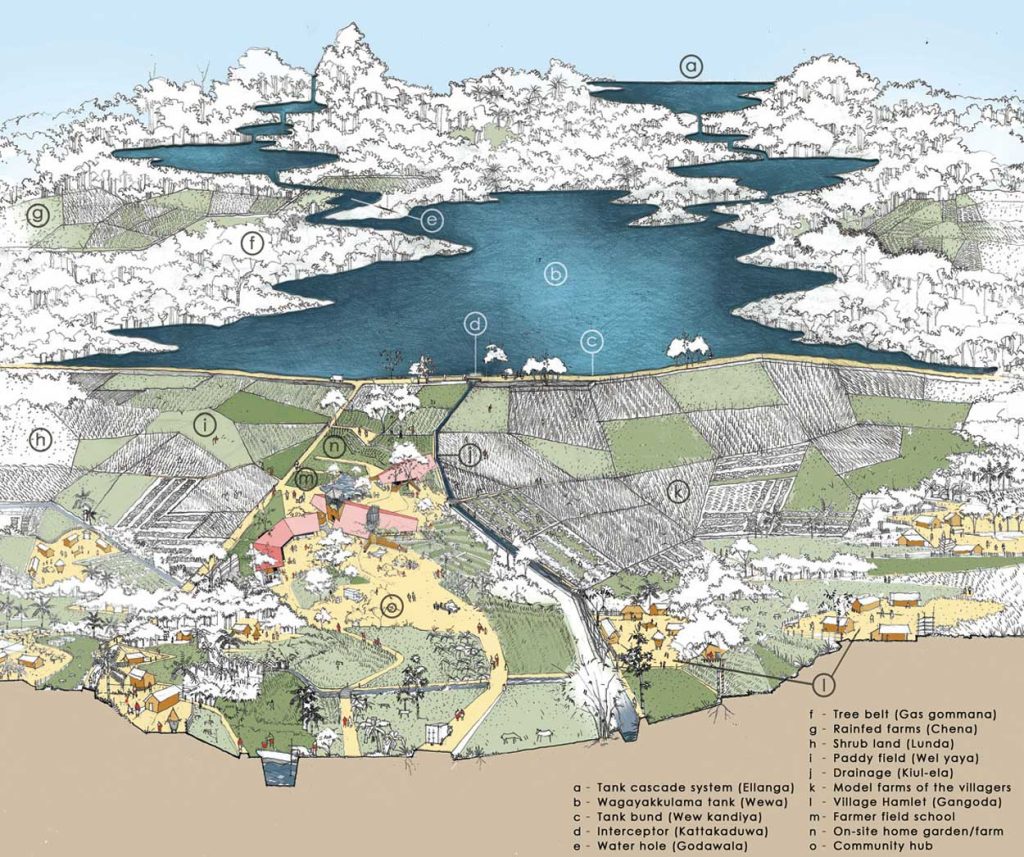

Looking back at Sri Lankan vernacular architecture, the fundamentals of this style were derived from climate responsive approaches such as harnessing and optimising the sun’s path for daylight, wind paths for air circulation to dictate openings within buildings and forms of roofs were based on rainfall. Materiality depended on resource availability and practicality, and spaces were positioned to complement the needs of everyday life.

These buildings were and are still identified as sustainable.

However, keeping up with the fast-paced world and technological advancements, we have somehow distanced ourselves from these principles. This does not mean that we have to go back to building houses using the vernacular method but merely requires us to adopt the fundamentals and implement them in a conscious way to suit present contextual demands.

In a conversation with Architect Malisha Kodituwakku about her perceptions of sustainability in an economically challenging fabric, she expresses her belief that if you’re truly passionate about something, you tend to make it a part of your design ethos, and be a more sensitive and empathetic designer.

“Sustainability does not need to be limited to smart systems and recycled materials; it can be as simple as conscious design. I feel that our focus needs to shift from merely creating beautiful pieces to creating those that also give back – to their users, the environment and the community. To me, that’s what real sustainability is: conscious and responsible design,” she explains.

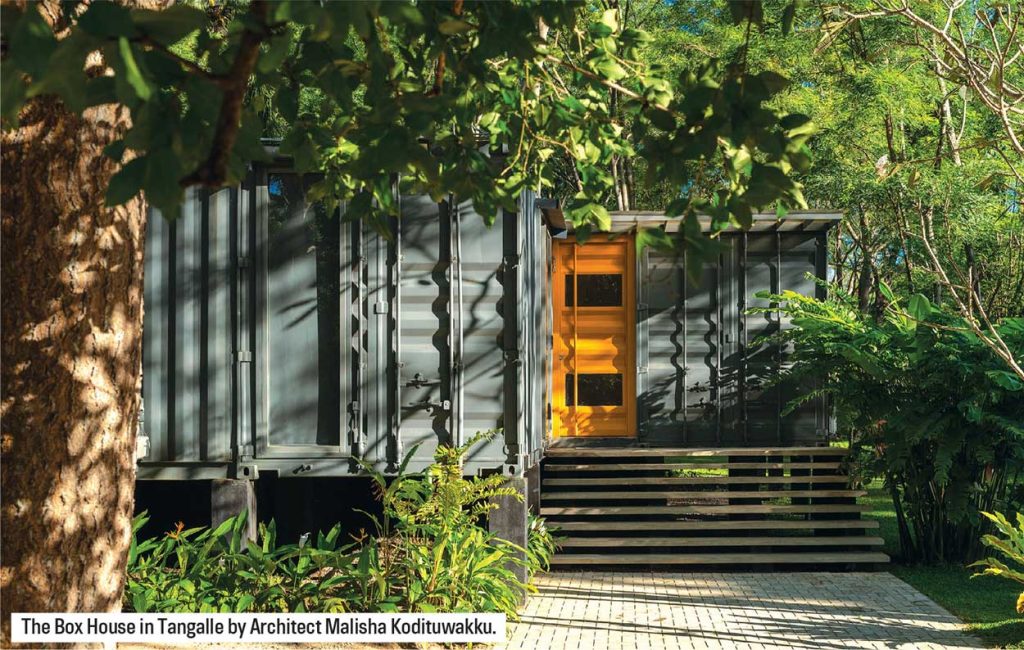

One of Kodituwakku’s most successful projects thus far, The Box House in Tangalle is a perfect example of adopting the concept of the traditional Sri Lankan courtyard house within a contemporary and unconventional construction setting.

The building is governed by nature, starting with its placement in the area with the largest natural clearing in order to preserve as many satinwood trees as possible.

“I let nature take that call, saving all but one tree,” Kodituwakku says.

The extensive brief that the client put forth was efficiently designed for a minimal footprint and new resources comprise less than 10 percent of the project, owing to the repurposing and retrofitting of discarded shipping containers in their raw forms with no external covering due to the abundant shade of the natural vegetation.

This building achieves the goal of minimising the carbon footprint of the project as a whole, and has minimal impacts on the surrounding environment with its simplicity in form and design.

As architects, it is essential that we utilise our creativity, and optimally use our training and expertise to work with the limited resources we have access to.

Bridging sustainability with the economy, and getting creative with material efficiency and systems is also another way forward.

How can we make current building materials more sustainable?

There are active measures to find alternatives to concrete. On the other hand, there is also research and development taking place on how to make concrete greener.

Given concrete’s versatility, it is by far the most common go-to material in the construction industry. There are methods to reduce the percentage of clinker, which can make up 95 percent in concrete, and replace it with alternatives such as Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3), developed by École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland, which has been widely looked at.

Architect Dr. Milinda Pathiraja is no stranger to making waves with his research and experimentation methods, and has an extensive portfolio of many sustainability ingrained projects that contribute a holistic approach to eco-conscious design.

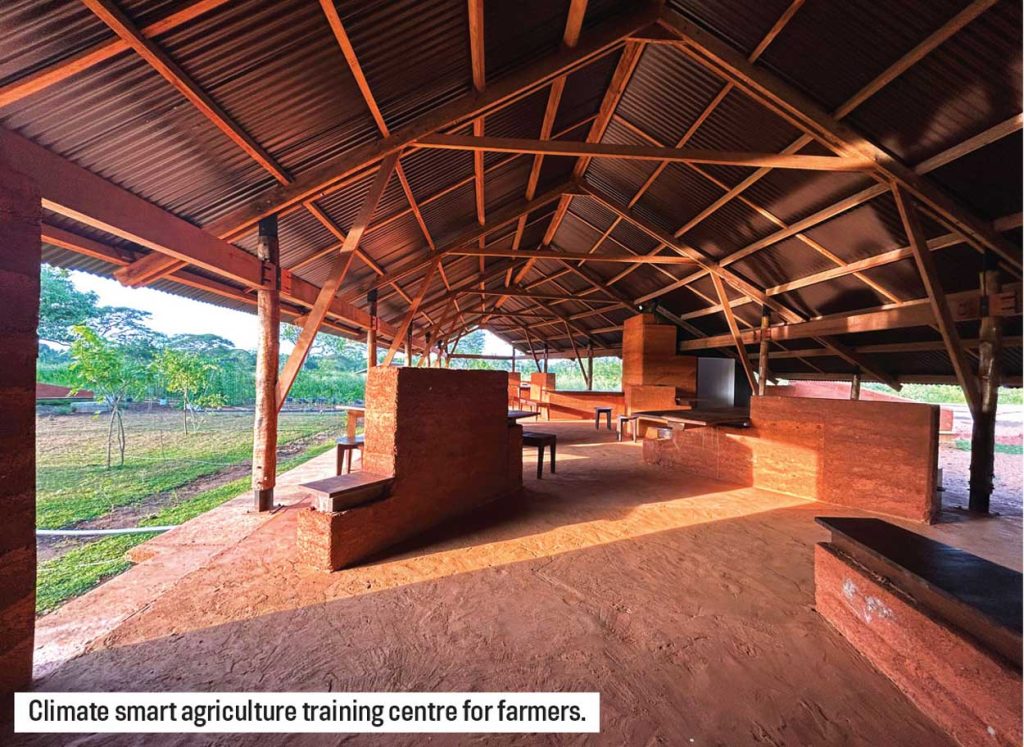

The climate smart agriculture training centre for farmers in Thirappane that was designed by his studio has successfully achieved the mutual integration of social, economic and ecological sustainability.

Designed against the backdrop of the economic crisis, this project centered on social sustainability where the functional aspect of the building catered to educating and training farmers in the locality on climate smart agricultural practices, and uplifting livelihoods.

The project was designed with minimal site intervention and resources, with raw materials such as earth and timber being sourced from local areas and spaces that relied on low embodied carbon. The agricultural spaces were also designed to be climate smart and efficient.

Pathiraja believes that it’s essential for architects to find solutions that are specific to the surrounding context, and each and every project is an opportunity to take a step towards inculcating a value system, and practising a style that allows your design philosophy to gravitate towards suitability and make better progress.

So where are we as a nation in this race to save the world?

We are currently caught in one of the worst financial crises since independence with the construction industry being severely affected and a climate crisis on the horizon. Practices are racing to hold on to their projects and complete them in the most efficient way they know while clients are looking to maximise revenue per square foot. Most often, the aspect of sustainability as a whole is lost in translation.

“Good consultants are the best investment you can make – and it is imperative that projects employ experienced and sensitive architects who will put in the required thought and detailing to make a project both climate sensitive and sustainable along its life cycle,” Kodituwakku says.

One of the issues faced in the local context is the mindset stemming from the point of view of the economic struggle where people are hesitant to build by engaging professional consultants’ inputs due to the added expense this may incur.

However, this has led to a large surplus of buildings that have no adequate light and ventilation, unregulated structures, and accessways and operational methods that may not only end up being health hazards to inhabitants but also threats to the environment as a whole.

Looking at various approaches to being sustainable in a tight economic backdrop, Pathiraja discusses finding alternatives to support this value system in a more efficient way: “There is currently a large stock of underutilised buildings across the city that could be optimally used rather than haphazardly constructing new buildings that won’t be utilised efficiently.”

He goes on to suggest that authorities could implement a system where incentives would be given for the adaptive reuse of projects that create a more circular construction system, which in turn would lessen the embodied carbon generated by new construction.

But how can we use the convincing power we once had as architecture students while being hounded by a panel of critics to ensure that our buildings worked in every aspect? Is that not what we were trained to do in reality? Should we look at developing and customising an education system that is more relevant to our context rather than borrowed syllabuses from developed nations?

Pathiraja stresses that “finding a way to develop the right dialogue with clients to make them see how we can give them incentives through sustainable design practices is so important. If you can make them understand that there is long-term gain, then that’s a huge step forward in creating a successful project.”

Architecture is a field that’s based on sustaining people, the environment and the way of life. How can we contribute to this while trying to sustain our profession as well?

We as a profession could look at these challenges through an optimistic lens that gives us room to create more opportunities to grow rather than crumble and continue to make sustainability a part of practice values.

Furthermore, we could consider breaking away from the linear mentality and structure of our education systems and workplaces, and adopt an approach that is intentional and integrated in our design ethos. Could we begin by looking at the fundamentals and reflecting on what architecture really is?

Kodituwakku notes: “The road to recovery – for both our economy and planet – is a long one. And while we can’t control how our country is governed, we can control how we design.”

“This needs to happen at the educational level. Architecture schools need to focus more on giving students the tools and techniques needed to design more sensitively – it should be so much more than one subject you study. We need to start there,” she emphasises.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Daria Scagliola (ArchDaily)

Malaka Mp

Kolitha Perera

RESOURCES

Architect Dr. Pathiraja, M. (2023).

Affordability Vs. Sustainability.

CPD June 2023, conducted by

the Professional Affairs Board.

Architect Malisha Kodituwakku, Studio Hexar.