SRI LANKANS OVERSEAS

AT THE MERCY OF CHANGE

Nishanie Jayamaha says Sri Lanka cannot afford to regress

Q: How would you assess Sri Lanka’s progress in the postwar era?

A: I left Sri Lanka in 2012, four years after the war ended. Since then, I feel the country’s infrastructure has improved and foreign investments have come in.

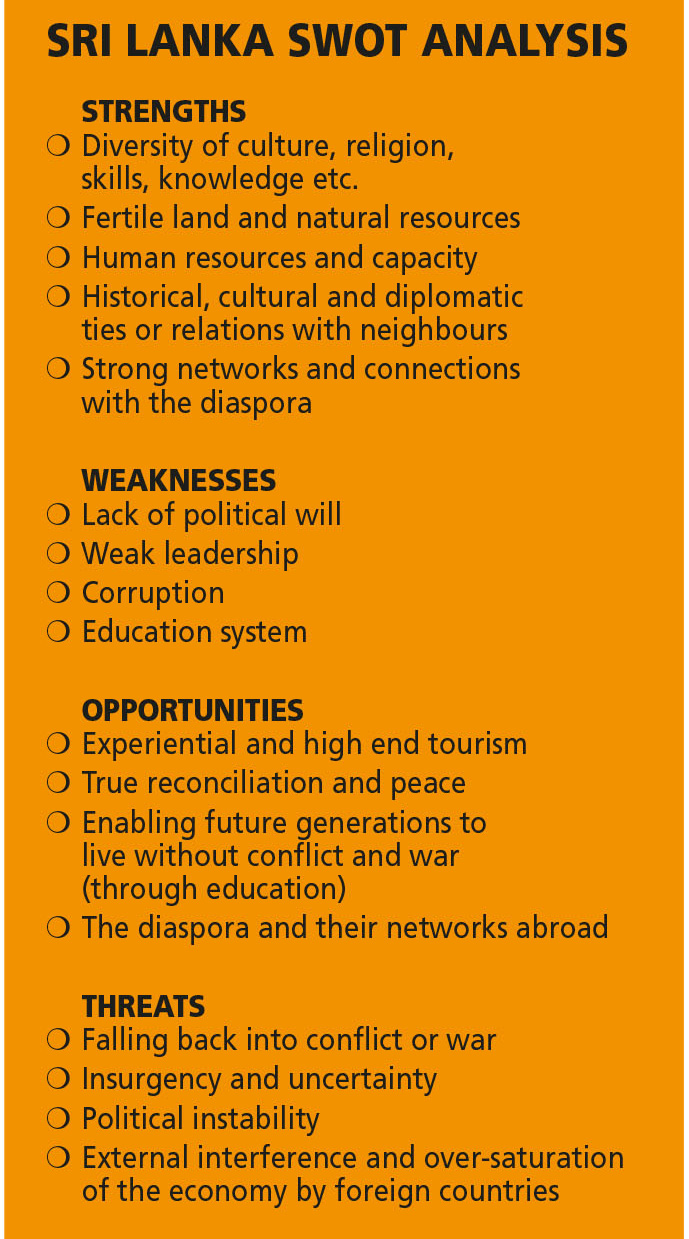

Sri Lanka has the potential to be a leading light in Asia and the world in many respects – e.g. tourism, value added trade or postwar reconciliation and rehabilitation. However, the political environment and people’s attitudes have to improve for this to eventuate.

While the war ended almost 10 years ago, recent clashes, racial discrimination and violent instigations – politically motivated or not – indicate cracks in our society. Changes in our mindset, attitude and perceptions of one another are required, if we’re to truly develop and grow as a society.

Without these fundamental building blocks, a nation will not blossom and reach its full potential.

Q: What were your impressions of Sri Lanka on your last visit here?

A: Since leaving Sri Lanka, I’ve returned every year. And each time, I see changes such as new hotels, roads, buildings and restaurants. It is also cleaner, which has amazed many of my foreign friends!

My greatest surprise was when visiting Kilinochchi and Mullaitivu in 2016. I barely recognised these areas, and it was heartening to see people slowly but surely rebuilding their lives and businesses.

However, some changes haven’t taken place. Much has to be improved in the context of attitude and behaviour. That is the most challenging change we need to achieve.

Q: How do your compatriots view Sri Lanka?

A: There was a lot of hope when the war ended but after a year or two, there was a downward trend.

There is a sense of frustration in Sri Lanka’s trajectory among my friends, family and former colleagues. Many cite the lack of a clear vision, unity and leadership, and continuing corruption and mismanagement as setbacks to real prosperity.

Many of my friends and family have thought about returning. Some returned but left again. Some who remained are contemplating leaving as they don’t see a future for their children. Some see and have tapped into the country’s immense potential but it’s a constant struggle – attitudes, bureaucracy and corruption impede development.

Q: What is your take on Sri Lanka’s brain drain?

A: This phenomenon has existed for a long time but the difference is that then, people wanted to return.

My father remembers the period from the 1950s to the late ’70s when those who educated themselves abroad longed to return home, and share knowledge and expertise for Sri Lanka’s betterment. After the 1980s, many left due to the conflict – for safety, better jobs, pay and positions overseas. It’s not only about money but also recognition, appreciating talent, innovation and valuing diversity.

I completed my education in Sri Lanka, worked until I was in my early 30s and then decided to leave as I did not see further growth in my field. We need to create space for all Sri Lankans to contribute meaningfully to the nation’s advancement.

Q: How can Sri Lankans living overseas be enticed to contribute or return to their country of birth?

A: Incentives and opportunities are needed to retain our most intelligent and innovative citizens before looking to attract those that have left the country for better jobs, pay and positions.

For those who are overseas, we need to tap into their expertise and vast network. Having lived in Geneva and New York, I note that Sri Lankans build networks, make friends easily, work hard and try to make a name for themselves.

For those who are overseas, we need to tap into their expertise and vast network. Having lived in Geneva and New York, I note that Sri Lankans build networks, make friends easily, work hard and try to make a name for themselves.

Sri Lankan missions overseas should engage the diaspora through a structured dialogue and look to invest in the country by way of expertise, knowledge, connections and networks. We do this through the Sri Lanka Association of Geneva, tapping into Swiss and Sri Lankan networks to support projects back home on preparedness, resilience and education among others.

Q: What should Sri Lanka focus on most in the coming decade?

A: We need to create a robust education system, which is key to addressing the root causes in any society. And we must start with younger generations to create harmony and build trust between ethnic communities.

Moreover, education should cater to the needs of the job market, community, country and foreign markets. From language to what we teach children, they play a part in incentivising citizens to shine, perform and contribute meaningfully.

Q: What are your hopes for the country in the post-conflict era?

A: My hopes are that we learn from the mistakes of regressing in development due to a nearly three decade war instigated by petty politicians and a narrow- minded few, and do not return to a state of chaos.

This goal might seem short term but in reality, it will take at least two generations to overcome pettiness, change mindsets and attitudes, and bring about harmony so that we can all work together to develop our country.

We need to acknowledge, appreciate and tap into our greatest assets – the diversity of our people, religions, cultures and resources. Once we start seeing the value of our collective and comparative advantages, we can truly soar. Indeed, the sky is the limit!

– LMD

As somebody with an avid appetite for this journal, I am a regular reader of this column and this has been the best answer to the question on the brain drain so far – honest and informative.

We certainly do need to create opportunities for everybody to contribute meaningfully for any development to happen. Replacing English as the official language, free education, universal franchise and nationalisation of the bus service were some bold attempts by governments of the past to create space for the vast majority if not everybody but even then, the brain drain did occur. To make matters worse, the brain drain has only intensified in recent years because the current situation is dire.

Yes, we cannot afford to go back to the past. There are some very important points in this interview.

I agree with Sam. It is too late.

I don’t think that this country has any hope.