ONE BELT ONE ROAD

REVIVING THE SILK ROAD

Yasmin Helal tracks China’s trajectory as it fills the funding vacuums created by the West

In January, a freight train from China reached the UK carrying 34 containers packed with clothes, shoes, suitcases and other goods made in China. Is it possible that the freight train returning from London to China carrying British goods is the UK’s escape from under the economic cloud that threatens it following Brexit?

Brexit will bring about a new era – one that bears the potential loss of the now easily accessible European market. But according to Brexiteers and their arguments, reaching markets like China and other global hubs is a reason why the bond with the EU became perceived as a burden.

China’s growing economy certainly looks more promising than Europe’s stagnant markets but whether stronger bilateral relations with it is more profitable for the UK is yet to be seen.

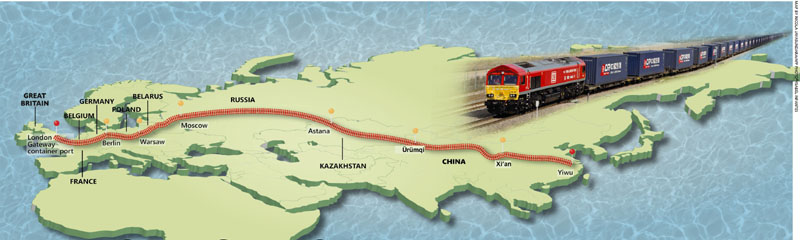

In the meantime, the 600-metre-long freight train that left London Gateway Terminal Port on 10 April returned to China some three weeks later with vitamins, baby products and other goods that the British seek to market abroad. The historic train journey covered 12,000 kilometres from eastern England to eastern China.

The train passed through the Channel Tunnel, France, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Belarus, Russia and Kazakhstan, to end in Yiwu in China. This is a Chinese initiative with the entire network being subsidised by the government.

In 2013, China announced its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), pledging over a trillion dollars to boost the development of transportation, energy and trade infrastructure from its western border to East Europe. President Xi Jinping unveiled it under the slogan ‘One Belt, One Road’ in an attempt to revive the ancient Silk Road.

Ambitions to bring back this ancient trade route began when the former Soviet Union countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus expressed a desire to enter international markets.

Today, the initiative to recreate the trade route covers 60 countries, 60 percent of the global population, 75 percent of energy resources and 60 percent of the world’s GDP – and it has become one of the largest infrastructure, economic and political developments across the globe.

Though freight by rail offers a more commercially viable option than air freighting goods – which is quicker and more expensive than shipping – trains aren’t suitable to transport fresh produce.

But there is a geopolitical angle to this new rail route that directly connects 16 cities in China with 15 in Europe. Here, China demonstrates yet another consistent move to fill a power vacuum as the UK cuts ties with Europe.

Indeed, China has repeatedly filled the gaps left by Western powers in the recent past.

When Russia was faced with sanctions by the US and EU in 2014 over the conflict in Ukraine and Crimea, China was the first to offer investment opportunities including a US$ 15 billion bid to build a high-speed rail line between Moscow and Kazan, as well as increased cooperation in various industries.

Similarly, when Sri Lanka was denied preferential trade concessions by the EU as a result of alleged war crimes charges in 2010, China stepped in and contributed to large-scale infrastructure projects that included a deep-sea port, a container terminal, an international airport, highways, a promising financial district and an industrial zone.

More recently, China also stood up for its neighbour when the US denied arms to the Philippines. President Rodrigo Duterte’s response to the US was: “I can always go to China.”

The West was previously accused of pushing these nations into building alliances with China and other anti-Western nations but the UK presents a slightly different case as it chose to exit the EU.

Its break from the EU provided the perfect platform for China to strengthen economic and political ties with a new ally, no less than any of the previous examples. And the UK is also in need of such an alliance as it prepares to face the post-Brexit world.

Major Chinese-led development projects are already underway in the UK, including the Hinkley Point C nuclear plant, a new US$ 2.12 billion Asian-focussed financial district in London and the Spire London project that aims to construct Europe’s tallest residential building. Recent studies also reveal that Chinese entities invested around five billion dollars in London properties last year alone. And a 2014 analysis noted that financial business in the Chinese currency grew six-fold in a mere four years while total deposits jumped by more than a third in only 12 months.

Together with these projects, the freight train will be yet another link aimed at strengthening ties between the two nations. The UK is the greater beneficiary in this case, leveraging from profitable trade with China and reducing its vulnerability following its decision to leave the EU.

Strategic moves like this will help China spread its wings over the West in the not-so-distant future.

Over the past 30 years, China has grown to be the world’s second largest economy with a population of over 1.3 billion, tipped to overtake the US within the next decade. China has been the largest contributor to world growth since the global financial crisis of 2008. It is predicted that China’s middle class will leap from around 100 million to 700 million people by 2020. China has lifted 439 million of approximate one billion people, out of extreme poverty since 1990. The Chinese consumer spending is expected to continuously grow.

Furthermore, China has embarked on a historic re-balancing from exports and investment to consumption, in order to boost the economy’s potential amid volatile global conditions. China’s fast-growing middle class has become a key driver of consumption growth as they seek more expensive and premium brands and spend more on high-quality goods and services.

The rise of the middle class in China is great for foreign business and the demand for imported goods in China is increasing year-on-year. The UK and other countries have the opportunity of tapping into this market.

China borders Afghanistan, Bhutan, Hong Kong, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, North Korea, Tajikistan, Vietnam and Russia by land; and Brunei, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and Taiwan by sea. And the Belt and Road Initiative aims to connect Asia, Europe and Africa along five routes.

The Silk Road Economic Belt focusses on:

01. Linking China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia;

02. Connecting China with the Middle East through Central Asia;

03. Bringing together China and Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean.

Meanwhile the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road focusses on using Chinese coastal ports to:

04. Link China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean;

05. Connect China with the South Pacific Ocean through the South China Sea.

Focussing on the above five routes, the Belt and Road initiative will take advantage of international transport routes, as well as core cities and key ports to further strengthen collaboration and build six international economic co-operation corridors.

These have been identified as,

01. The New Eurasia Land Bridge,

02. China-Mongolia-Russia,

03. China-Central Asia-West Asia,

04. China-Indochina Peninsula,

05. China-Pakistan,

06. Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar.

Therefore, maintaining bilateral trade relations with China will open up not only the Chinese market of the 1.3 population, but beyond that.