MONETARY POLICY

SPECTRE OF HIGHER INFLATION

Samantha Amerasinghe investigates a series of narratives behind the recent financial market volatility

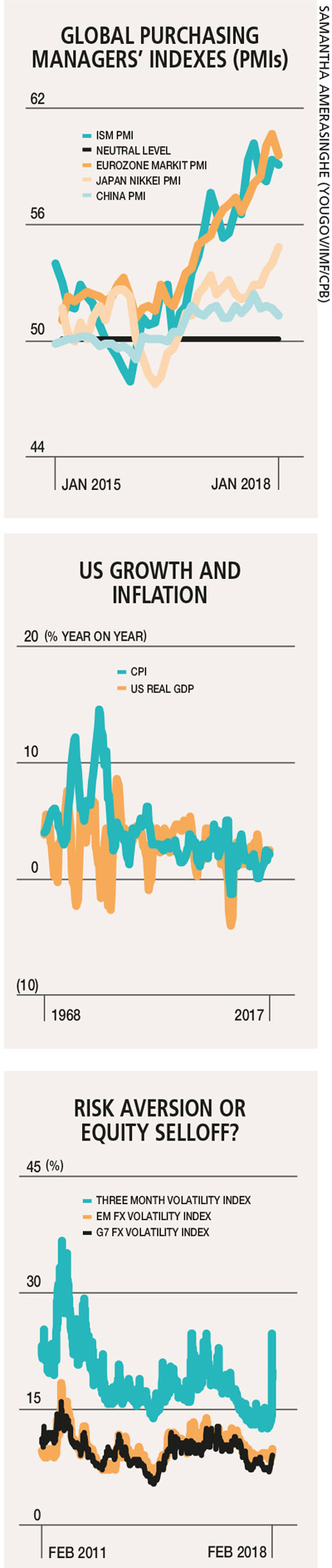

The turbulent period witnessed in the financial markets in February was driven in part by speculation that higher inflation would prompt the US Federal Reserve to increase interest rates more than the three hikes pencilled in by policy makers in December.

Inflation looms as a threat to global economic recovery. And the spectre of higher inflation has spooked markets as strong global growth raises concerns that price pressures will increase.

In attempting to explain the recent market volatility, there are two narratives. Was it merely a technical correction or the start of something more? Is inflation or the fear of it back to bite us?

Some experts argue that it could potentially be the beginning of a change in thinking for markets as all asset classes adjust for the likelihood of rising inflation.

A substantial rise in US inflation is one of the top risk scenarios to watch out for this year. After nearly a decade of being almost invisible, tentative signs have emerged that inflation could accelerate in the coming months, driven by jobs recovery and tighter conditions in the US labour market.

Both core and headline US inflation measures are increasing faster than investors had expected, leading to speculation in financial markets that the Fed is preparing to accelerate its programme of interest rate increases.

The US labour market is now near or a little beyond full employment, according to the Fed. This is apparent even in industries where hiring has slowed because workers are harder to find – e.g. in transportation and hospitality where wages growth has remained steady or slowed. If the Fed sees scope for further strengthening in the job market, it will remain reluctant to stand in the way by tightening policy too aggressively.

Untested new Fed Chairman Jerome Powell will face a major challenge if inflationary pressures continue to build. A key question is whether Powell, a hawk, is prepared to raise rates in the face of a stock market selloff.

Some analysts forecast that the Fed will raise rates four times in 2018 and twice more in 2019 with the Fed Funds Target Rate (FFTR) reaching three percent at the peak of the hiking cycle. Policy tightening in the United States will have an impact on other major central banks’ monetary policies. The outlook for monetary policy over the coming months for major central banks is as follows.

Despite quantitative easing, it remains puzzling that a number of advanced economies are experiencing low inflation. The Fed suggests that this could be due to “more persistent factors” restraining price growth. One possibility is that the natural rate of unemployment – i.e. at which the job market neither pushes up inflation nor holds it back – could be lower in some countries than many economists assume.

The ECB has acknowledged that strong cyclical momentum and reduced slack in the economy should lead inflation to converge on its two percent target. But domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to display convincing signs of a sustained upward trend.

Net asset purchases at the new monthly pace of EUR 30 billion are intended to run until the end of September or beyond if necessary. One observes upside risks to the outlook with rate hikes not expected before 2019. But the ECB cautions that volatility in the exchange rate – a source of uncertainty – could pose downside risks to price stability and growth, and must be closely monitored.

Inflation in the UK has edged higher in recent months, further strengthening expectations that the Bank of England’s (BoE) next rate hike will come within three to six months. The BoE will likely target 10 May when the next Inflation Report is released. But there is heightened risk that a Brexit shock (if differences on the transition agreement and Irish border issue cannot be resolved in a timely manner) could change the policy imperative.

In Japan, consumer confidence – which is stabilising at a moderate level from its recent high – hasn’t been sufficient to boost domestic demand. Despite the rise in inflation in recent months, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is unlikely to change its accommodative policy stance. Inflation remains well below BoJ’s two percent inflation target in spite of its aggressive approach under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda.

BoJ has hinted that an exit from ultra-easy monetary policy is some way off but seems more upbeat on the trajectory of inflation. Inflation expectations are expected to recover further with the continuity of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy.

China’s monetary policy stance is likely to remain neutral in 2018 despite rising inflation with policy makers expected to continue to balance growth and deleveraging. Stable growth at 6.8 percent year on year in the fourth quarter suggests that the People’s Bank of China will adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach to making further adjustments to monetary policy.

We maintain our view that inflation dynamics will not be a major driver of the monetary policy stance.