FISCAL STABILITY

MITIGATING THE RISKS POSED BY SOEs

Shiran Fernando examines the role played by local state owned entities in fiscal volatility

When one reviews the country’s budget deficit, the tendency is to consider factors such as VAT or roads built with public finances. While the former contributes to state revenue, the latter is a part of its expenditure. The balance between revenue and expenditure helps compute the budget deficit for a given year.

However, one item that may not make the headlines but plays a major role in the fiscal picture with an impact beyond a year is the performance of state owned enterprises (SOEs).

Sri Lanka has more than 200 such SOEs ranging from hospitals to hotels with the total asset base of these entities accounting for nearly 57 percent of GDP last year.

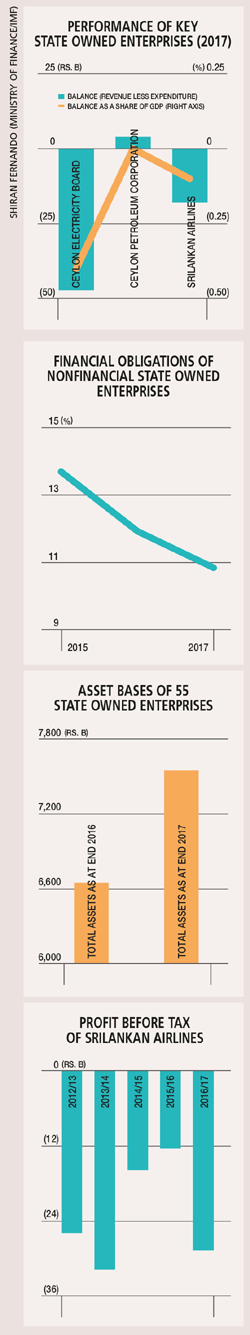

NATIONAL IMPORTANCE To illustrate the importance of SOEs in simple terms, the budget deficit for 2017 was 5.5 percent of GDP but for nonfinancial SOEs – not all but most critical entities such as the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) – the financial obligations amount to 10.8 percent of GDP.

This poses major economic and fiscal risks to the country.

These obligations consist of items such as short-term loans linked to subsidies and project loans. In some cases, SOEs have their debt absorbed or guaranteed by the government – and as such, they exert pressure on state banks to continue to guarantee such debt or roll it over.

Another example of this hefty burden is the level of profitability of these SOEs. Of the 55 entities monitored by the Public Enterprise Department, 39 recorded a net profit of Rs. 136 billion while 16 incurred net losses amounting to 87 billion rupees. The 16 loss making entities have proved to be a drag on the cumulative or overall profitability of SOEs.

TIME TO TURN AROUND SOE reform has been part of the dialogue of successive governments although most have not been able to carry out the key reforms that will likely reduce the debt burden of the state.

One of the pillars of the current IMF programme is focussed on SOE reform. As a first step, five major SOEs published their statements of corporate intent with related key performance indicators last year to bring about greater accountability and transparency.

There is also a positive trend in terms of a decline in the financial obligations of critical nonfinancial SOEs.

In 2015, this figure as a share of GDP was 13.7 percent and by 2017, it had dropped by 2.9 percent. This near three percent decline is owing to the CPC paying off some of its debt in 2016 (due to lower oil prices) and by lease proceeds from the Hambantota Port improving the Sri Lanka Ports Authority’s (SLPA) financial position.

AIRLINE RESTRUCTURE When considering the much talked about SriLankan Airlines, there is now a move to implement restructuring measures that will reduce the operational and financial costs of the national carrier.

On average, during the period from 2011 to 2017, the airline accounted for between 0.1 and 0.4 percent of GDP. If one were to consider this in terms of profit before taxes, it would point to a cumulative loss of around Rs. 114 billion in the last five years. One hopes that efforts to improve the commercial viability of the national airline will help it attract a strategic investor.

PUSH COMES TO SHOVE One part of ensuring that these entities are commercially viable – or at least that they generate operational profits – is to ensure that their services reflect the cost of providing them.

While this may not be politically popular (as it could increase the cost of providing services and therefore, the cost of living), providing services at subsidised rates has proved to be unsustainable.

This is observed in the profitability of the CPC, which benefitted from the low price of oil in 2016 with a profit of Rs. 69.6 billion compared to a loss of 5.1 billion rupees in 2017 amid rising oil prices. The change in profitability highlighted the unsustainability of subsidies and stagnant prices that were not reflective of global trends.

As for the market determined pricing formula for fuel, the government missed an opportunity to introduce it when global oil prices were much lower – than for instance, they were in May.

It was introduced at a time when oil prices were at a three year high and had increased by 55 percent since the previous fuel price change in January 2015. The government is now expected to introduce an automatic pricing mechanism for electricity by September in line with the IMF’s structural benchmark.

As already highlighted, SOEs are a crucial part of the fiscal and macro narrative. While steps have been taken – albeit at a slower pace than expected – political will, as well as public awareness and concern, will be needed to reduce the risks posed by SOEs.