LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION

SRI LANKA’S GENDER GAP

There are gender disparities in the local labour market

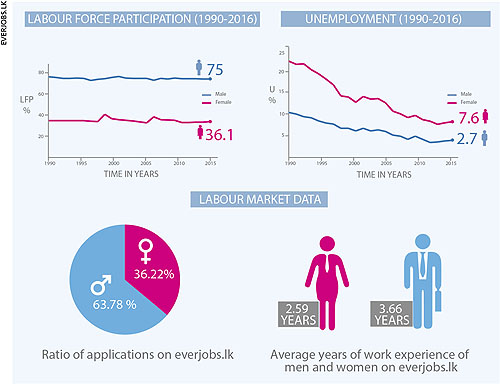

The female labour force participation (LFP) rate in Sri Lanka stood at 36 percent, according to the Sri Lanka Labour Force Survey for the third quarter of 2016. With a male LFP of 75 percent, Sri Lanka has the 17th-largest gender gap in the world.

In terms of unemployment, things do not necessarily look better. While a female unemployment rate of 7.6 percent may not seem particularly high, compared to the 2.7 percent unemployment rate among the male labour force it certainly is.

Why is this the case and what can be done to address it?

PRIMARY REASON There is ample evidence why women are discouraged or even prevented from (firstly) joining the labour force and (secondly) finding employment.

PRIMARY REASON There is ample evidence why women are discouraged or even prevented from (firstly) joining the labour force and (secondly) finding employment.

While one can easily point to the lack of access to vocational training or protectionist legislation applying to maternity leave with employers bearing the full cost and thus often discriminating during the hiring process, culture is the undisputed primary reason.

That women should run the household is unfortunately an all too common opinion. This additionally leads to women bearing a disproportionate share of unpaid work when caring for children.

Culturally, working women are seen as providing a supplementary income to the household rather than being equal or primary earners. And they’re discouraged from seeking employment if their male counterparts earn sufficiently high incomes.

THE STATUS QUO With a little less than two-thirds of women not actively participating in the labour market, Sri Lanka is unable to exploit their economic potential to the fullest. Therefore, it’s apparent that a higher female LFP is crucial for the economic development of the country.

A Sri Lanka-based career platform has gathered and analysed data on the national labour market, and found that 36.2 percent of applicants for employment opportunities online were females while 63.8 percent were males.

Another noteworthy fact is the discrepancy in average work experience – 2.6 and 3.7 years for women and men respectively. These numbers provide additional evidence of the problem vis-à-vis the status quo and highlight the need for change.

THE CHALLENGE The government clearly faces a major challenge. And only by gradually implementing targeted policies would the country be able to address the issue structurally and sustainably. In this regard, the most efficient strategy would be to motivate females to get started as early as possible – e.g. by actively encouraging them to work while studying for their A-Levels or following tertiary education.

Flexible work environments, affordable care services and assurances of a more even distribution of household responsibilities (introducing paternity benefits, for example) are among the measures for systemically improving female participation in the long term.

This will certainly take time but is imperative if Sri Lanka is to advance from being a lower-middle-income country.