INTERPRETATIVE SKILLS

UNDERVALUED EXCELLENCE

Dr. Devika Brendon underscores the value of the arts and humanities

Broadly speaking, if we want to organise and prioritise the issues that concern us today into a ‘to do’ list, there are survival and fulfilment issues to consider. When it comes to fulfilment, the systematic dismantling of the arts and humanities as school and university subjects is an issue that is of paramount importance in how our culture navigates the challenges ahead of us.

My view is that certain essential skills are only accessible through the valuing of arts subjects, which teach us problem solving in a sequential, illuminating and context driven way.

We have been increasingly told recently – by government ministers all over the Western world – that arts subjects such as history and literature are now often classified as nonessential.

Of course, this is a subjective and false statement, masquerading as an official objective and authoritative announcement, which reeks of political agendas and selective misinformation. This attitude directly contributes to the problems these nations face in effectively managing the new globally connected world in which we live.

There’s a systematic process involved in discrediting anything whether it’s a person, an organisation or a subject of study. You begin by undervaluing and questioning its relevance, you discredit its practitioners, you measure its productivity in solely fiscal terms without factoring in its social and cultural impact, and you start to underfund its institutions.

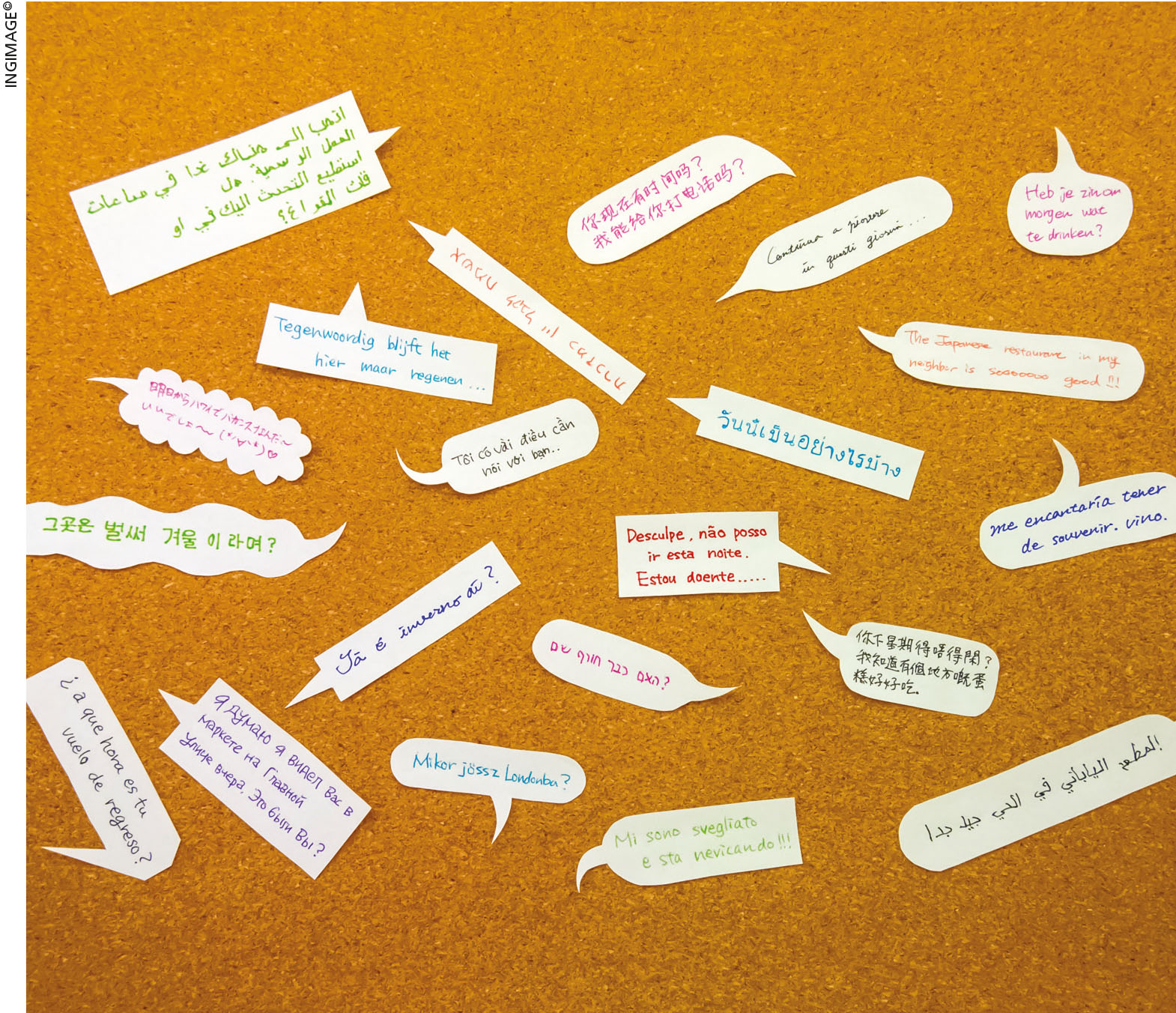

What skills can language and literature teach us?

They teach us intellectual and discernment skills to analyse the written and spoken word, as well as how to accurately interpret what we read. We become able to filter out sensationalisation, exaggeration, understatement, euphemism, selective omission, obfuscation and distortion.

Moreover, we’re able to identify the triggering adjectives used by writers and speechmakers to detonate our emotions. We learn to feel the impact of cumulation and structural devices in text. And we can understand not only what is being said to us but the intention of the person presenting it.

These skills of analysis and interpretation are crucial to enable us to comprehend and process the huge amount of information, sensation and misinformation that comes our way.

We also learn to communicate our own ideas most effectively.

If we don’t develop these essential skill sets, we become passive consumers of information and susceptible to manipulation; and as a result, we may become overdependent on preprocessed information, susceptible, fearful, and confused participants in the societal spread of misinformation and fake news.

All of us have witnessed what damage this can cause in our personal experience, society and online communities.

Fifty years ago, school curricula were not so specialised. There was a much broader emphasis on liberal humanities as a foundation of education. Scientists studied history, geography and literature, while medical doctors and economists also studied fiction and poetry. These were not viewed as luxury or niche subjects, and the professionally trained minds that resulted were respected worldwide.

Today, with Sri Lanka’s emphasis on science, technology, engineering and mathematics, (STEM) subjects to build the economy, we may overlook the fact that how we enjoy and comprehend our lives is as important as our material wellbeing.

In my opinion, we’re even more vulnerable to the erosion of the skills of critical thinking relative to other countries because we currently offer language and literature as an option at secondary school level rather than as the building blocks of information literacy that they should be.

It should not be difficult to incorporate analytical and interpretative skills into any online course that students can access. And the benefit would be manifold: a citizenry that is empowered, articulate and information literate.

Skills of analysis and interpretation are crucial

Leave a comment