FUTURE INVENTORS

SRI LANKA AT THE ROBOTICS OLYMPICS

BY Angelo Fernando

A short walk from the White House, the steps leading up to a neoclassical building where Robin Williams once performed spill over with teenagers in bright yellow and blue T-shirts. Using screwdrivers and wire, they are feverishly fixing their robots. It’s only 15 minutes before Round 1 of the two-day competition held in July – a global event drawing 163 teams from 157 countries.

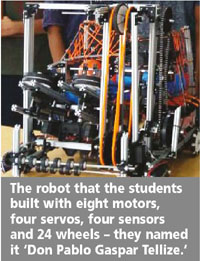

The humidity in Washington D.C. hovers around 90 percent and Team Sri Lanka’s four students are sweating bullets. Huddled in a basement, and parked between Senegal and Sudan, their 20-wheel steel robot needs some repair work.

Why?

The bot they had built in a classroom (so secretive was the project, they called the room ‘Area 52’) arrived with a warped axle and damaged omni wheels. The motor failed too, which is not an uncommon problem among teams here. In a few minutes, they must have their 23-kilogramme robot working.

It is the ‘Olympics,’ after all…

GRAND VISION If all this sounds daunting and super annoying, it is really part of the experience anticipated by FIRST Global, which organised this event – the ‘Robotics Olympics.’

Its vision is to promote science and technology, leadership and innovation by motivating students from across the world to increase their understanding of the subjects and address pressing global issues. The event is the brainchild of Dean Kamen, the renowned inventor with more than 400 patents to his name (including devices for dialysis, diabetes and the iconic Segway).

“The future of the planet depends on this generation working not as competitors but ‘alliances’ to solve our most challenging problems,” he emphasises.

And he checks them off rapidly: water, medicine, education, food insecurity, energy and global conflict. Quite a lofty goal for what might seem a pretty geeky event. Speaking to LMD in June after sending invitations to Sri Lanka, the President of FIRST Global Admiral Joe Sestak claimed that “more valuable than the competition is the collaborative piece.”

A former congressman who served as ex-president Bill Clinton’s director for defense policy in the White House, Sestak notes that “the big payback when we allow young people convene would come when they go on to address the common problems facing their country.”

In other words, the fate of the world rests in the hands of these A-Level (or high school) students. “The robot is only an excuse,” says Kamen, adding: “It allows these young people to learn together and design a future about which quite frankly we grownups have done a poor job.”

THE COMPETITION This is a robot game designed around the theme of access to clean water and is played over five rounds. Teams are organised into two ‘alliances’ – three country teams in each alliance are randomly selected on the morning of the competition.

The game begins in an ‘arena’ roughly the size of two Ping-Pong tables with six bots trying to identify and store contaminated water (represented by orange balls) while collecting as many blue balls, which represent clean water.

As the coloured balls continue flowing down the river, team members must drive the robots using an app and a Bluetooth-tethered game controller in two and a half minutes. By the end of the round, each alliance also scores extra points if their robot leaves the path of the flowing river and lifts itself up on to a metal bar using another manoeuvre!

Team Sri Lanka – which worked with France and Romania in Round 1, and Spain and Panama in Round 2 – were excellent at strategy. They were coached by Dilum Rathnasinghe, the ICT teacher at Elizabeth Moir School. “Planning was important but in reality, things don’t always go exactly to plan,” he concedes, adding that “our team learned how critical it is to act quickly, and discuss and find common ground.”

In a high stakes ‘Olympic’ event like this, language and culture can be an issue but I watched in amazement at how each alliance worked through these constraints, often helping each other out of technical glitches.

In the educational technology space, this is called ‘gamification’ – using game design to enhance learning outcomes. Kamen places much weight on the ‘just do it’ principle of problem solving. “Why wait for someone in authority to come up with the perfect plan when we could make progress by just doing it?” he asks.

Some in the press misread this event and asked: “What is the value of all these kids building robots?”

“You don’t understand. All these robots are building kids!” he tells them.

No wonder they’re sweating bullets.

THE ROBOTICS ERA Robotics is no longer something that exists on the fringes when you consider the giant strides being made by drones, remote sensing and artificial intelligence (AI).

No less than the four tech giants – viz. Google, Amazon, IBM and Facebook – as well as many other organisations have invested heavily in robotics.

Between 2010 and 2015, approximately 80,000 industrial robots were installed across the US, Europe and Asia. It is already impacting sectors that range from medicine and farming, to manufacturing and environmental monitoring… and even news – think ‘drone journalism’!

In the near future, biologically inspired robots could be working in close proximity with humans. As a robotics coach, I collaborate with Arizona State University where researchers are developing such things as a ‘swarm’ of robots that could soon carry out tasks that are too dangerous for humans.

Autonomous cars and surgical robots are the new normal. By 2019, 2.6 million units of industrial robots will be deployed worldwide. Some of these jobs that are related to robotics haven’t even been invented. Indeed, a few predicted personal bots like Alexa from Amazon or Cortana from Microsoft would take off.

Is Sri Lanka ready for this? And more importantly, are schools geared to motivate a new cadre of young people for these careers?

The Information and Communication Technology Agency of Sri Lanka (ICTA) plans “to build an ecosystem for digital education technology.” Robotics is the perfect ‘on-ramp’ for this.

Rajan Anandan – who had his primary education in Sri Lanka – is the Vice President of Google for South East Asia and India. He views the challenge very clearly: “Computing needs to be taught from Grade 4 but for this, we need to invest in computer labs.”

Anandan also stresses the need to invest in good teachers, acknowledging that his career was impacted by great mentors in schools. He believes that Sri Lanka should be introducing students to fields such as machine learning and AI.

The Director of Corporate Strategy at Dell Technologies Hisham Mabrook agrees:

“In the 1990s, I had to wait till I was in college to understand biometrics and surgical robots. It’s about time we began exposing Sri Lankan students to the big trends early.”

Indeed, some schools like D. S. Senanayake College and Devi Balika Vidyalaya are investing in this future with robotics clubs. Others are hiring industry practitioners to introduce STEM – science, technology, engineering and math – domains. Moreover, the University of Moratuwa holds an annual ‘Sri Lanka Robotics Challenge.’

Students at Elizabeth Moir School are introduced to Information Communication Technology (ICT) in the early grades while Kids Ignite holds robotics workshops for young students between the ages of eight and 14. But at a policy level, things are moving at a much slower pace.

The National Institute of Education (NIE) plans to introduce a STEM approach to schoolwide curricula. The Director of the Department of Science at NIE Premalal Uduporuwa is convinced that robotics could provide students with the skills that are necessary for the 21st century. He states: “Robotics involves problem solving and transforms learners from consumers to makers.”

But there is more work to be done.

In the meantime, the Chairman and CEO of Virtusa Corporation Kris Canekeratne notes: “In Sri Lanka, every student should be exposed to technology, design and problem solving; not lectures. Think about it. The upcoming generation or Gen Z began ‘swiping’ before they were crawling! They intuitively learn from being hands-on in activities and gamification.”

The challenge is not to change what we teach but how we teach. As Kamen said, the robot is merely the excuse – a ‘hook’ to make learning more hands-on. Robotics and STEM provide a new template that the next generation will need as they face tomorrow’s challenges head-on.