EU-UK TRADE

BORDER ISSUES CONFRONT BREXIT

Samantha Amerasinghe takes an in-depth look at the agenda for the months ahead in the lead up to Brexit

Brexit has been in the background in recent times but is back in the headlines following the House of Lords vote against the government and in favour of a customs union (CU). The British government remains firmly opposed to a customs union although it would help resolve the Irish border issue. The EU has always been sceptical about the UK’s proposals to avoid a hard border in Northern Ireland.

It is becoming increasingly difficult for the British government to avoid a head-on debate about the UK staying in a customs union with the EU after Brexit. This warrants an in-depth look at the agenda over the coming months in the lead up to Brexit and where potential problems may surface.

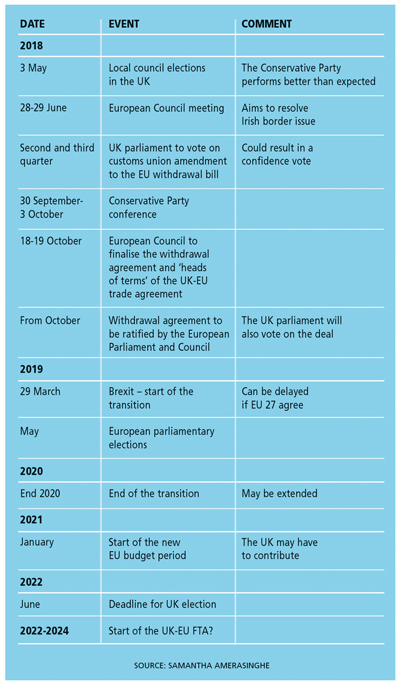

Britain has reached an agreement in principle for a transition arrangement whereby very little changes for 21 months once it leaves the EU on 29 March 2019. Most aspects of the withdrawal agreement have been settled but important outstanding issues such as the Irish border remain.

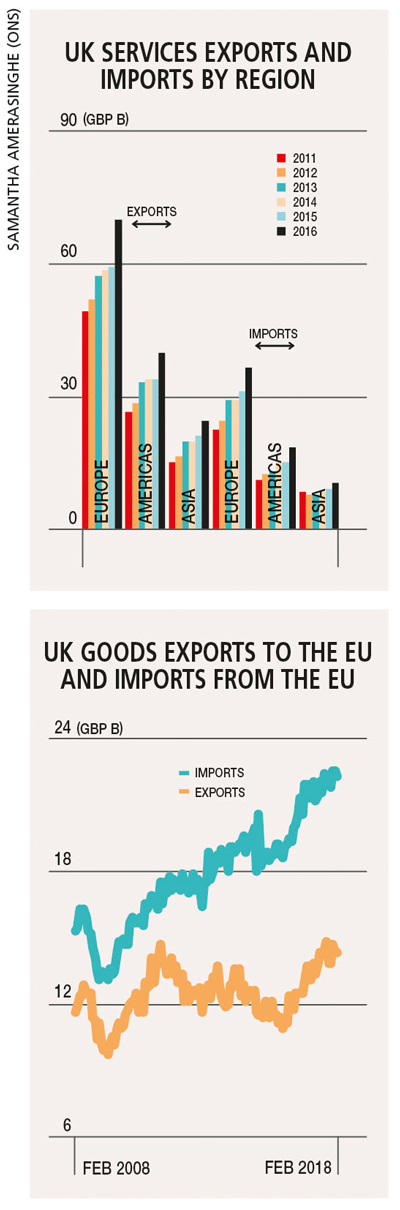

Furthermore, the UK has to agree on the outlines of a post-Brexit trade deal with the EU 27. Britain wants an enhanced FTA that would encompass a broad range of areas including financial services, fisheries, aviation, motor, transport and data movement. But the question is how far Brussels is willing to go beyond a bare bones Canada style FTA dealing mainly with goods.

By the time the European Council meets at the end of June, the two sides want to make progress on the ‘heads of terms’ of an FTA.

There is growing support in the British parliament for a form of CU; an arrangement where EU countries impose a common external tariff but allow goods to circulate freely within the union – tariff free and without complex rules of origin checks. A customs union would help resolve the Irish border issue as well as potentially ease the renegotiation of current EU FTAs with third countries.

‘Brexiters’ are opposed to CU membership as it could prevent the UK from striking new trade deals with other countries. For investors, a CU type agreement would likely be regarded positively.

If the Irish border issue is resolved to the satisfaction of all parties, the risk of a chaotic Brexit diminishes. But a cliff edge risk looms over January 2021 unless the transition can be extended. Negotiating an enhanced FTA would likely require longer than the 21 months of the transition period so businesses might have to plan accordingly.

Ahead of the 28-29 June European Council meeting, progress will need to be made on some important unresolved decisions carried over from the March agreement. Key issues yet to be resolved include the Irish border, governance, geographical indicators and various technical issues. Gibraltar – the subject of bilateral talks between the UK and Spain – is a potential stumbling block. Separately, the UK and EU are discussing a heads of terms agreement on a future UK-EU trade deal.

The British government has so far rejected a full CU arrangement following Brexit as it would constrain the UK’s ability to negotiate trade agreements with third countries. Its solution is to align certain sectors with the EU – either UK or Ireland wide. The EU however, is sceptical.

Ultimately, it is down to the Irish Republic (backed by the rest of the EU) to determine whether cross border issues are properly addressed by the UK. The republic is highly vulnerable to a ‘no deal’ outcome and the British government believes that a solution can be found that avoids formal CU membership.

The British government aims to have the withdrawal agreement finalised by around October although the process may take longer. This leaves little time for further talks or a change in direction. The agreement will need to be ratified by the British and European parliaments.

Following the consent of the European parliament, some 40 FTAs that the EU has with third countries will need to be rolled over so that they continue to apply during the transition period even though the UK will technically be outside the EU.

Moreover, the Withdrawal Agreement and Implementation Bill (WAIB) must receive royal assent and become law by the date of the UK’s exit from the EU. Experienced trade negotiators doubt that anything more than a basic FTA can be agreed on and ready to be implemented within 21 months – the time from Brexit in March 2019 to the end of the transition period in December 2020.

The transition period could be extended beyond December 2020 although pro-Brexit politicians oppose an extension. It would require changing the withdrawal treaty, which would need the support of the council as well as the European and British parliaments. An extension could come with a price attached, given that the EU’s new budget begins in 2021.

Meanwhile, the UK government would want to finalise negotiations ahead of the next general election, which is due by June 2022.