COVER STORY

ECOSYSTEM FOR GROWTH

Amena Arif emphasises that greater access to finance and greener practices will fast track national development

“Financial inclusion is a key strategic pillar for our work in Sri Lanka and a priority for the World Bank Group’s mission to achieve universal financial access by 2020,” said Amena Arif, IFC Country Manager for Sri Lanka and Maldives. As IFC partners with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka to develop a National Financial Inclusion Strategy, this “will improve access to and usage of financial services, and contribute to inclusive growth,” she asserted.

In this exclusive interview with LMD, she highlights the importance of supporting micro and small businesses across the island, and emphasises that training and development of human capital are crucial to boosting economic growth in Sri Lanka.

Arif also looks at other key aspects of IFC’s strategy for Sri Lanka including infrastructure development and helping businesses adopt more sustainable practices.

She outlines the major economic growth drivers in the region, suggests areas for improving the ease of doing business in Sri Lanka, and looks at how the private sector globally can be a “force in developing solutions to combat corruption”

– LMD

Q How important are micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) for Sri Lanka’s economy – and what must be done especially by the state to support their growth?

A MSMEs are critical for economic and social development across emerging markets such as Sri Lanka. There is clear evidence that such enterprises create the majority of jobs and thereby boost economic growth. Therefore, it is vital that conditions are made favourable to support their growth.

The major issues for MSME growth are largely the same around the world. These are centred on limited access to finance and credit, and a lack of diverse insurance schemes or risk mitigation tools.

Our research indicates that as of 2011, the SME financing gap in emerging markets was estimated at between US$ 900 billion and US$ 1.1 trillion. In Sri Lanka, 38 percent of all SMEs face constrained access to finance. That percentage jumps significantly when we include the micro sector. And this really stops them from being able to reach their full potential – MSMEs are more likely to generate jobs and at a faster pace when they have access to finance.

But access to finance is not the only limiting factor – overall, MSMEs need an ecosystem that helps them grow. This includes an enabling environment in the form of appropriate regulations and processes. Elements such as collateral registries or capacity building within banks to lend to SMEs, or adequate capital market tools will all ultimately unlock the potential of MSMEs.

Q What are the primary objectives of the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS)?

A To put it very simply, the NFIS aims to promote a more effective and efficient process to improve financial inclusion across the country.

Financial inclusion is achieved when households and businesses have access to and can effectively use a range of appropriate financial services, which are provided responsibly and suitably – and in a well-regulated environment. Financial inclusion is pretty much the need of the hour for sustainable and continued economic development.

Yet, we find that around 2.5 billion adults in the developing world don’t have access to financial services such as payments, credit and savings accounts. Over 600 million of them live in South Asia alone.

Locally, the scenario is very interesting. Sri Lanka has a wide range of financial services providers, high levels of physical access to branches and a large number of accounts. Yet, financial inclusion remains a key constraint for growth across many sectors, with persistent gaps including a limited range of products and services that effectively cater to the needs of the population.

There’s also a minimal focus on women. For instance, only 17 percent of women have been successful in borrowing from the formal sector and over 80 percent of borrowers in the informal microfinance sector are women.

Here, the question is less about the un-banked and more about the underbanked – whether people use their accounts and how they do so. Despite a high bank account penetration rate, over 31 percent of individuals reported no deposits or withdrawals in the past year.

These statistics indicate that there is great potential for better financial access and inclusion.

And that’s where we come in. At IFC, a rather large component of what we do is focussed on improving the regulatory side to make it more conducive for banks and institutions to expand their reach, narrow the financing gap, catalyse SME growth and boost financial inclusion.

IFC has an able and willing partner in the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). We have partnered with the CBSL to create the NFIS for a coordinated and systematic approach toward financial inclusion.

Of course, this is not something that IFC or CBSL will do by ourselves. This process will involve extensive consultations with members of the public sector, private sector, civil society organisations and academia. The NFIS has to be a homegrown solution that is specific, accessible and responsive to the needs of the population.

Q Do you believe that enough is being done to develop infrastructure in Sri Lanka? On the other hand, how do you view this country’s mounting debt?

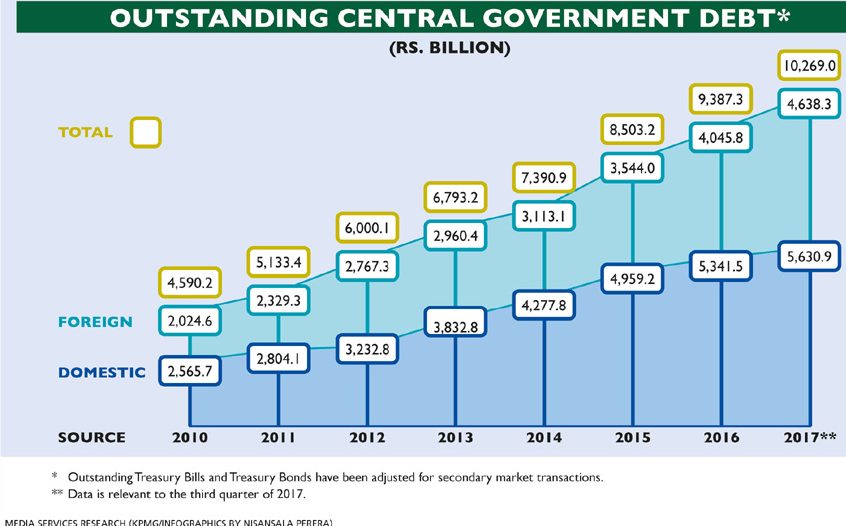

A For a middle income country, Sri Lanka is clearly struggling with an infrastructure gap, both in terms of quantity as well as quality and efficiency. Successive governments have pursued infrastructure growth on a priority basis. But a lot more needs to be done – and a lot that can be done differently.

So far, the bulk of the spending on infrastructure in the last several years has been by the public sector and this is clearly unsustainable. The World Bank Group (WBG) recognised that given the multiple demands on the public purse, it is not possible for governments alone to fulfil development needs. It is critical to mobilise the private sector for this. This is what IFC and the World Bank have embraced as the ‘cascade concept.’

Essentially, the cascade conversation is to ensure that scarce public funds are directed towards projects where there’s no ability or viability for the private sector to come in. For other needs, the private sector should be mobilised to invest. We call this Maximising Finance for Development (MFD). Infrastructure is an area that typically plays well for MFD.

The primary reason for bringing in the private sector is to introduce efficiencies that the public sector typically cannot provide. This can be done in a variety of ways like for instance well-structured public-private partnerships (PPPs). Increased private sector involvement in infrastructure investments required will also help ease the fiscal burden on the government.

IFC strongly believes that it is vital for the private sector to be an important partner to achieve the government’s infrastructure aspirations. We are supporting the government on a number of projects across various stages of development including Sri Lanka’s first water PPP.

Q Which key aspects must be considered with respect to human capital as well as training and development?

A When we talk to businesses locally, a key impediment to growth is the lack of a skilled workforce. We actually have a shortage of adequate vocational and technical skills in the workforce – skills that are increasingly in demand. One study found that only 16 percent of workers know how to use a computer and 24 percent have proficiency in English.

Importantly, the links between vocational training centres and industry are missing. In fact, 46 percent of employers indicate that job specific skills are the most important factor in deciding whether to retain a high skilled worker. When it comes to advanced skills and human capital, Sri Lanka has few highly skilled workers, and there are constraints on the quality and relevance of higher education and research.

More generally, there are poor linkages between where the private sector needs to innovate and R&D institutions that could meet these needs. Within the SME sector, small businesses find it difficult to grow and reach their potential, due to a lack of basic management and business skills.

To narrow this gap, it will be important to invest in education and training, and enhance the dialogue between the private sector and the education system to ensure that people gain the skills demanded by high productivity enterprises.

Creating a better skilled labour force will really help Sri Lanka become more competitive, including within global value chains, as well as a more attractive destination for foreign direct investment (FDI).

Q How would you characterise the ease of doing business in Sri Lanka – what are the pros and cons?

A With Sri Lanka’s current ranking of 111th of 190 economies on the Ease of Doing Business index 2018, clearly this is an area where there are several challenges.

It is encouraging to note that the government recognises this as a key area for it to focus on. Several initiatives from Customs and the Board of Investment (BOI) to land registration have been launched already.

Over the years, Sri Lanka has developed a rather complex regulatory environment in almost all sectors. Multiple agencies with sometimes overlapping areas of responsibility make it challenging for local and foreign investors to operate. This again is a particularly tough challenge for MSMEs that have limited management bandwidth.

Land acquisition is a good example of an issue that businesses face when 80 percent of the land is owned by the state. Again, the state is also a major player in several key industries and a large user of domestic credit (37% of loans went to state owned enterprises last year).

The taxation regime has been simplified considerably with the new Internal Revenue Act. But Sri Lanka’s import regime remains one of the most protectionist and complex in the world.

These are all issues that the government is trying to tackle. In our capacity as partners to the government, we are engaged – both through IFC and the World Bank – to assist in the necessary investment reforms.

Q What is your take of the present-day concept of ‘sustainable business’ (including green finance)? And are there any barriers to progressing along this path?

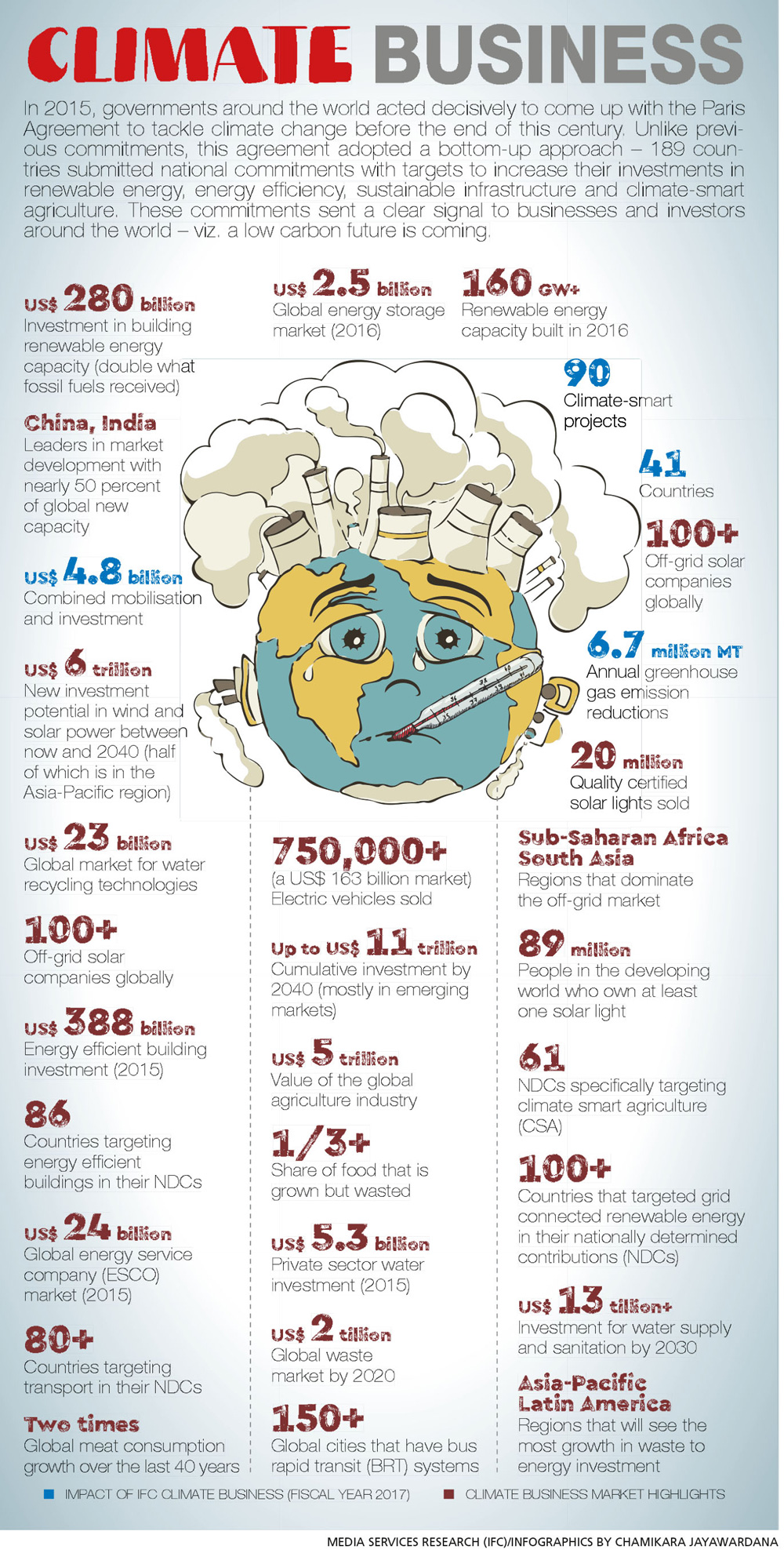

A Global growth is placing an unprecedented demand on our finite resources.

Three billion people will join the global middle class by 2030 – and therefore, come out of poverty – and there will be billions more trying to get themselves out of poverty. If they follow the path of developed economies by clearing forests, burning coal and oil, and engaging in liberal usage of fertilisers and pesticides, they’ll put further pressure on our natural resources.

In Sri Lanka, the effects of climate change in terms of altered and severe weather patterns are painfully obvious. Less obvious may be our growing vulnerability to increasing temperatures and rising carbon dioxide levels. The results of climate change can and will impact key economic sectors such as agriculture, tourism, energy, water and infrastructure – we face an estimated 1.2 percent loss of annual GDP by 2050 if measures are not taken to address climate change.

Sustainable growth – through more responsible and inclusive business practices – is therefore, critical. And governments and businesses across the world are taking important steps towards a fundamental transformation of the global economy to build a more sustainable future.

A dramatic drop in the price of clean technologies and the rise of smart policies are driving businesses to climate-smart investments. Governments and business are investing more than 300 billion dollars annually, to improve the efficiency of power grids, transport, industry and buildings.

The global green building market continues to double in size every three years. Climate smart agriculture is also a growing private sector opportunity as companies seek to increase crop resilience and food productivity, as well as their profits.

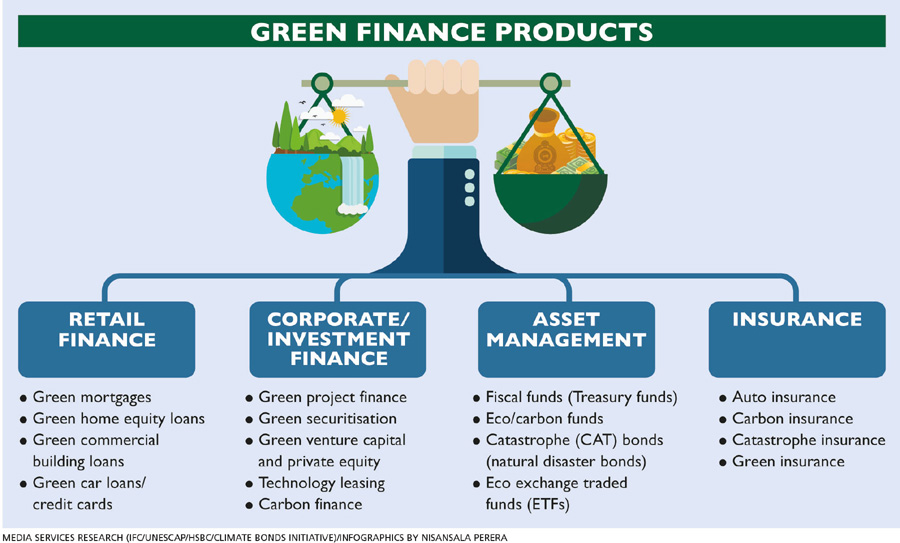

Moreover, the financial sector is a key partner in this transformation. Less than 10 percent of the 50 trillion dollars in banking assets across emerging markets is in green finance. We must drastically increase the amount of financing directed to green projects that have positive environmental impacts.

At IFC, we believe that sustainable finance is one of the most powerful tools at our disposal to achieve the objectives of the Paris Climate Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals. In fact, we are one of the world’s largest financiers of climate smart projects. In Sri Lanka, we are working with the Central Bank to develop a sustainable finance road map and I’m quite excited about the impacts that this can have. Sri Lanka has the potential to become a regional and global leader in sustainable finance.

Q How is regulation playing a part in accelerating the uptake of sustainable finance by the banking sector?

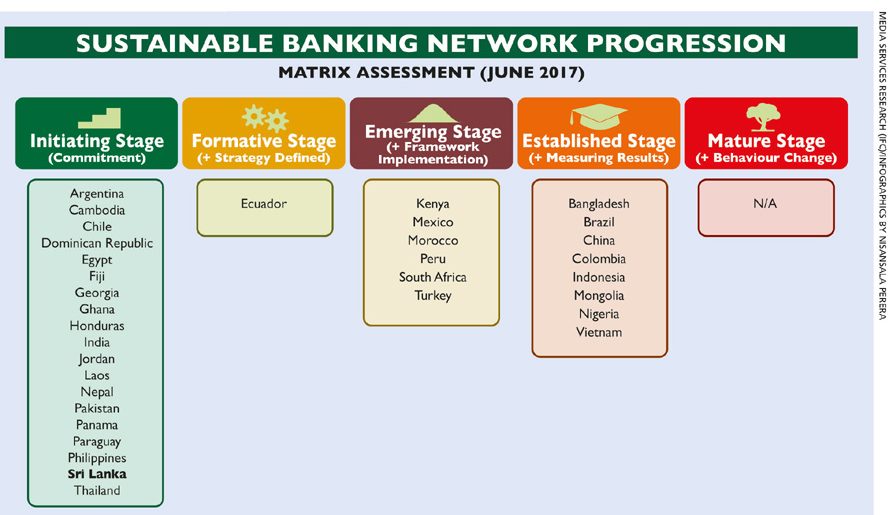

A Sustainable finance is a critical component of the international development agenda to ensure a prosperous future for the next few generations. And Sri Lanka is already well placed in its journey towards sustainable finance.

Just last year, CBSL joined IFC’s Sustainable Banking Network (SBN) to enhance and develop environmental and social risk management, and sustainable financing practices, for Sri Lanka’s financial sector.

Under this partnership, the Central Bank is collaborating with the SBN to develop a sustainable finance road map to guide the local banking and finance sector, strengthen the capacity of the banking sector, facilitate knowledge sharing with other SBN members and promote green investment.

Sri Lanka is in fact quite unique. There are 18 banks that have already adopted 11 voluntary principles under the leadership of the Sri Lanka Banks’ Association. Through our partnership with the Central Bank, we hope to provide a clear vision for Sri Lanka’s sustainable finance journey.

Q What role do partnerships play in moving the sustainability agenda forward?

A Partnerships are vital. They’re the only way we can collectively work towards a more sustainable economy. Partnerships enable the exchange of global best practices, knowledge and experiences – and as such, are critical to help us move forward on the sustainability agenda.

As mentioned earlier, the Central Bank recently joined the Sustainable Banking Network – a unique community of financial sector regulatory agencies and banking associations from emerging markets committed to advancing sustainable finance in line with international good practices.

The network facilitates the collective learning of members, and supports them in policy development and related initiatives to create drivers for sustainable finance in their home countries. As a member of this network, the Central Bank will benefit from the experience and knowledge of other members while receiving technical support in green finance from IFC.

Partnerships of this nature are the best way to learn, understand and make any form of significant change.

Q In your opinion, what are the chief economic growth drivers in the region?

A South Asia is a diverse region and the key sectors driving growth vary. However, increased consumer demand from the region’s growing middle class has boosted GDP across the board.

Today, India is one of the fastest growing economies in the world on the back of public investment and private consumption. Bangladesh’s recent robust growth performance – driven by both robust export performance and strong consumer demand – has propelled it to lower middle income status. Sri Lanka has registered positive results despite climate disasters and increased external volatility.

Q Has there been adequate progress in poverty reduction – in Sri Lanka, South Asia and the world?

A Overall, Sri Lanka’s record of poverty reduction since 2002 has been quite encouraging by regional standards. When compared with international standards, the poverty level is low – at less than seven percent of the population.

To look at cross-country comparisons, the World Bank Group currently uses an extreme poverty line of 1.25 dollars a person a day. Using this measure, extreme poverty in Sri Lanka has decreased from 13 percent in 2002 to less than three percent in 2012/13. This is lower than many of Sri Lanka’s neighbours, and other post-conflict countries and comparable nations. However, while the decline in poverty was strong, progress in reducing poverty has not been universal. It was below what one could have expected given the sustained high growth rates over the last decade.

In many other regional and developing countries, an increase in per capita GDP would reduce the poverty rate at a higher rate than we observe in Sri Lanka. The goal of shared prosperity in Sri Lanka is particularly important for us given the country’s history.

Q What is your estimation of the cost of corruption in nations such as Sri Lanka, what must be done to reduce or eradicate its incidence and who is to blame for it becoming endemic in so many parts of the world?

A Corruption is easily one of the biggest obstacles to economic and social development globally, and impacts those who are hardest hit by economic decline, most reliant on the provision of public services and least capable of paying the additional costs associated with corruption.

One thing is clear; in dealing with corruption across the world, there are no simple answers; it is a drain on public trust, and on the legitimacy of public and private sector institutions.

The effects of corruption can also be devastating for an economy particularly at a time when open global markets can rapidly reverse investment and capital flows. Personally, I believe that the private sector can be a force in developing solutions to combat corruption – and we’ve seen companies around the world taking charge in a number of ways. These private sector solutions to corruption however, are not only external in nature and so many companies are also beginning to look inwards.

One way of addressing the issues that businesses face is through the establishment of strong corporate governance. This is probably even more important for public sector companies. Good governance requires transparency and accountability. This makes the environment far less conducive to corruption.

Q In the context of corporate governance, what are the main concerns in this day and age?

A Good corporate governance helps companies operate more efficiently, improve access to capital, mitigate risk and safeguard against mismanagement. It makes companies more accountable and transparent to investors, and provides them with the tools to respond to stakeholder concerns.

Corporate governance also contributes to development. Increased access to capital encourages new investments, boosts economic growth and provides employment opportunities.

IFC’s Corporate Governance Program in South Asia helps strengthen markets and stabilise businesses across the region by providing advice to companies, SMEs, private equity funds and banks on improving their corporate governance practices.

This is based on international standards with a focus on board practices, shareholder rights, internal and external controls, risk management, transparency, family business governance and reporting, regulatory enforcement and dispute resolution.

Our efforts also include building local capacity and working with multiple market stakeholders to promote broader acceptance of good corporate governance practices that sustainably improve financial performance, operational efficiency and access to capital. To do this, we work with regulators, stakeholders, corporate governance institutes and the media, to raise awareness and share knowledge.

Q In what ways can women contribute to private sector growth through corporate leadership?

A There is so much compelling evidence on the importance of board diversity and equality in the workplace – not merely because this is the right thing to do but because it also makes good business sense.

Women CEOs in the Fortune 1000 Companies drive three times the returns as S&P enterprises run predominantly by men. Globally, companies that had strong female leadership generated a return on equity of 10.1 percent a year versus 7.4 percent for those without.

Additionally, multiple studies reveal conclusively that the more gender equal companies are, the better it is for employees. And the happier their employees are, the better the companies perform.

Diverse and professional boards lead to well-run companies. Board diversity can have positive impacts on financial performance, shareholder value, investor confidence and reputation. Recognising this, companies globally are improving their hiring and promotion practices to ensure that more women rise to the top.

Corporate leadership is an area where women are making a vital contribution to private sector driven growth throughout the emerging markets world.

Our research indicates that women on boards in Sri Lanka make up more than eight percent, positioning Sri Lanka slightly ahead of the Asian average of 7.8 percent.

In fact, a part of IFC’s new DFAT-funded Women in Work Program revolves around raising awareness, building capacity, and expanding the discussion on board diversity to ensure that more companies can retain and attract senior women to serve on their boards.

We want to promote diversity on boards through research on the business case by working directly with companies on good corporate governance practices, by helping support the supply side or pipeline and by supporting training for women executives and boards.

– Interviewed by Zulfath Saheed

Leave a comment