ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

SLOWDOWN ON THE CARDS

Shiran Fernando describes the factors that are contributing to the global slowdown

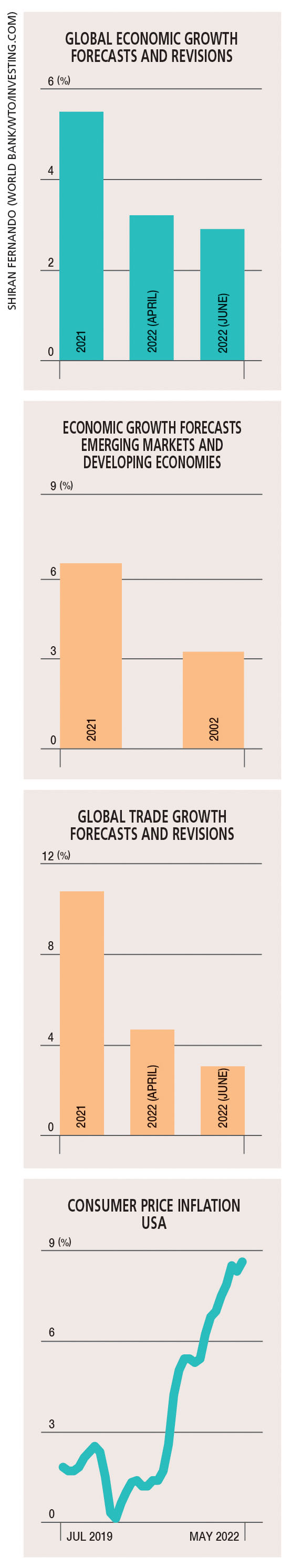

Concerns about a global recession are high with many forecasters now predicting that the world economy may slow down from its post-pandemic recovery. The World Bank – in its Global Economic Prospects published in June – expects growth in the year ahead to be 2.9 percent – down from 5.7 percent in 2021.

Three months ago, the bank’s forecast for 2022 stood at 3.2 percent. The key factor for the downgrade is the impact of the Ukraine-Russia conflict on economic activity.

Let’s explore the implications of the unfolding situation and what it will mean for Sri Lanka, which is in the throes its own economic turmoil.

KEY DRIVERS The chief driver has been the Russia-Ukraine war, which has accounted for 1.2 percent of the World Bank’s downward revision in growth. It has undermined investor confidence, disrupted food supplies from both countries and accelerated global inflation.

The Ukraine-Russia conflict and pandemic-related lockdowns in China during the first half of this year are dampening global trade. In April, the WTO forecast a three percent growth in merchandise trade volume for 2022 – down from the 4.7 percent that it was predicting in October last year.

With inflation rising, central banks across the world have reacted and more Group of Ten (G10) countries raised their policy rates in June. This kind of response hasn’t been seen in the past two decades or so and it reveals the concerns that these nations have with inflation reaching multi decade highs.

For instance, the US Federal Reserve raised its policy rates by 0.75 percent in June – the single largest hike since 1994. Expectations are now rising that US policy rates will be much higher than previously forecast for end-2022 with rising inflation.

IMPLICATIONS The growth in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) are also expected to slow down. The World Bank expects growth to drop to 3.4 percent this year, from 6.6 percent in 2021, due to the above reasons.

If these forecasts are to materialise, it will be the weakest year of EMDE growth since 2009 – barring the pandemic induced recession in 2020. Due to the slowdown, per capita income in developing economies is expected to fall this year and be nearly five percent below the pre-pandemic trend.

This has significant implications for social stability and more people will fall under the poverty line in their respective countries.

There are already signs of a slowdown – with manufacturing data from the US to Asia showing how factories are facing issues related to supplies, labour shortages and the rising cost of materials.

In June, American manufacturing activity weakened to a two-year low – with the Factory Purchasing Managers’ Index in South Korea, Thailand and India showing substantial declines.

While raising interest rates could cool demand pressures, it will certainly slow down economies with higher borrowing or lending costs. Consumers will also be more inclined to save rather than consume and this could have implications on exports out of emerging market countries such as Sri Lanka.

The island depends on the US and EU for a large share of its exports, and this slowdown would affect exports such as apparel and rubber.

Rising interest rates also increases borrowing costs for emerging markets with higher yields and interest rates. With Sri Lanka locked out of capital markets due to its downgrade and sovereign debt default, increased volatility in markets could make refinancing of debt, accessing trade credit and other transactions more difficult.

POSITIVES While there are major risks from a slowdown on our export growth potential and broader economic recovery, there remain some potential upsides too. A key benefit would be the slowdown or decrease in global commodity – particularly oil – prices.

For example, the price of oil fell nine percent in trading on 5 July – its largest fall since March – due to growing fears of a global recession and slowdown in demand because of lockdowns in China.

If the expectation is for a further fall in demand, mainly from key developed economies such as the US, then oil could potentially fall further and to under the US$ 100 a barrel mark. This will be positive for Sri Lanka, which is finding it difficult to finance fuel imports; it would also reduce our fuel bill, which has climbed primarily due to fuel imports.

If we continue to see similar slowdowns, other commodity prices including those of food may slow down and ease the pressure on Sri Lanka’s headline inflation, which surpassed 50 percent in June.

RECESSION While these dynamics could have short-term (i.e. six to 12 months) implications for Sri Lanka, the concerns expressed by most forecasters revolve around whether the global economy will be in recession for a brief period or the next few years.

The latter would not be beneficial for a country that’s trying to emerge from its own domestic economic crisis.

Leave a comment