CURRENCY CRISIS

NO TURKISH DELIGHT FOR THE LIRA

Samantha Amerasinghe analyses the primary reasons for increasing concerns over Turkey’s currency crisis

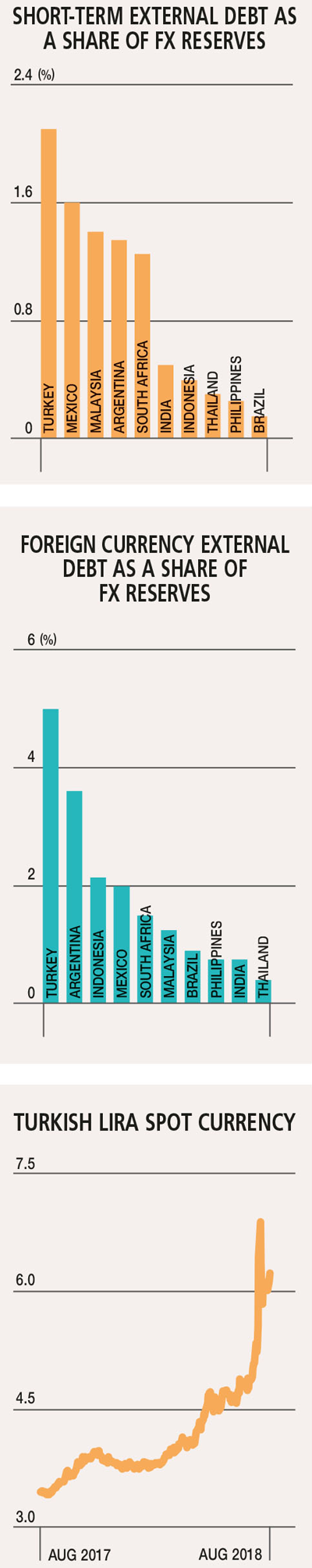

Turkey is grappling with a currency crisis and heightened tensions with the US, its NATO ally. The Turkish Lira has fallen by some 40 percent (that’s more than the Argentine Peso) against the US Dollar in recent months, driven by deteriorating relations with the United States and a current account deficit that has triggered a currency meltdown.

This has set off a wave of selling across emerging markets, reviving fears of contagion – and there’s a risk that this contagion will gain momentum. Economies afflicted by twin deficits (current account and fiscal) and large short-term foreign currency external debt are most exposed. And Turkey is the most vulnerable.

Turkey’s worst currency crisis since 2001 is being driven by fears of further US measures, as well as growing external vulnerabilities both at the sovereign and banking sector level. Turkey has proved to be the most vulnerable emerging market to changing global risk sentiment and its banking sector remains a key source of vulnerability. Strains in the sector seem to have eased but banks face large external debt repayments over the next few months, which could cause stress.

Much of Turkey’s weakness is compounded by its reliance on external funding. This is important as concerns spread beyond its borders to both emerging and developed markets.

Turkish banks’ dollar bond spreads remain high, suggesting that markets continue to be concerned that it might default on large external debt repayments falling due over the next 12 months. Even if banks avoid a worst case where they default on these debts, tighter external financing conditions mean that they won’t be able to expand their foreign borrowings, which has funded the recent credit boom.

Banks are more likely to repay their external debts, causing their balance sheets to shrink. As a consequence, credit growth is likely to slow sharply and painfully. If banks were to default on these debts, this may be the catalyst for the government to turn to the IMF to avoid an altogether more severe economic and financial crisis. Turkey will have to endure a painful period of adjustment if it decides to request a loan from the IMF.

A couple of mitigating factors might prevent such a severe outcome.

For one thing, banks appear to have hedged their on balance sheet FX mismatches through off balance sheet instruments, generally through the use of foreign currency swaps. They also have fairly large foreign currency assets of around US$ 80 billion deposited at the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT).

Markets are pricing in a substantially higher risk of default than they were some time ago. Spreads of Turkish banks’ five year dollar bond yields over US Treasuries now stand at a little over 1,000 basis points compared to 500 points prior to the lira’s latest plunge.

Inflation was accelerating even before the latest crisis, reaching 15.8 percent year on year in July – and it is likely to rise to around 25 percent year on year in the coming months. The central bank has raised its average cost of liquidity provision modestly (and hasn’t raised official interest rates) but local currency bond yields have risen sharply. Financial conditions have tightened dramatically as a result.

So far, US measures against Turkey have been limited to sanctions against Turkey’s justice and interior ministers, following the arrest and detention of a US pastor, with an announcement that the United States would seek to double tariffs on imported steel and aluminium from Turkey.

The US was Turkey’s fifth largest export market in 2017 after Germany, the UK, the UAE and Iraq with exports totalling 8.7 billion dollars (5% of total exports). Including imports, this puts bilateral trade at US$ 20.6 billion (5% of Turkey’s trade). However, markets are likely to remain nervous about the likelihood of further measures being imposed.

Capital controls are unlikely particularly in the context of Turkey’s external funding needs. Turkey’s first half 2018 current account deficit totalled 31 billion dollars. This was led by a US$ 34 billion trade deficit, half of which was financed through the financial account, and the remainder through net errors and omissions with a drawdown in reserves.

While CBRT’s gross reserves stood at slightly over US$ 107 billion in May, major contingent liabilities comprising commercial banks’ deposits with the central bank put Turkey’s net reserves closer to 30 billion dollars. It is imperative therefore, for Turkey to sustain capital inflows to avoid a balance of payments crisis.

Turkey’s fundamental macro weakness – viz. insufficient domestic savings to finance economic growth – is once again in focus. The economy’s prospects, a top priority for President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, remain contingent upon continued capital inflows.

Strategists blame Turkey for the weakness in many Asian emerging market currencies. But the combination of withdrawal of liquidity from developed market central banks, slowdown in demand from China and to a lesser extent, a surge in oil prices account for pressure on the most vulnerable of these economies.

The key to the current emerging markets’ turmoilis Fed tightening and a strong dollar – not Turkey’s macro idiosyncrasies.