COVER STORY|WOMEN IN BUSINESS|LOGISTICS SECTOR

EXCLUSIVE

NAVIGATING UNCHARTED WATERS

Kasturi Chellaraja Wilson

Zulfath Saheed gains valuable insights into the logistics sector and its role in the big picture scheme of things from one of contemporary Sri Lanka’s most prominent women in business

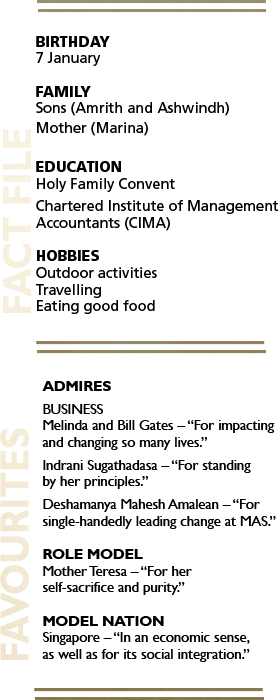

Counting over 26 years’ managerial experience in multiple sectors and functions spanning auditing, consulting, logistics, travel and leisure, Kasturi Chellaraja Wilson joined the diversified conglomerate Hemas in 2002 as the Finance Director of Hemtours (presently, Diethelm Travels).

Three years later, she was appointed Head of Shared Services for the group and subsequently, Chief Process Officer of the group, in 2007. In 2011, she took up the position of Managing Director of the Transportation Sector. And recently, Wilson was appointed Managing Director of Hemas Pharmaceuticals and Hemas Logistics and Maritime.

A Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) UK and presently serving as a Board Member of CIMA (Sri Lanka), Kasturi leads from the front, in a field that isn’t traditionally blessed with females in the upper echelons of senior management.

For her services to the logistics sector, she was recently honoured at the 3rd World Women Leadership Congress – held in Mumbai, in mid February – with an Outstanding Women Leadership Award.

The logistics sector holds a special place in Wilson’s corporate repertoire. She has championed the cause of enhancing Sri Lanka’s maritime logistics, drawing on expertise and know-how gained from exposure to innovative solutions embraced by global maritime hubs such as Singapore and Hong Kong.

In an exclusive interview with LMD, she emphasises that Sri Lanka is “in a position to become a logistics hub for the region, and act as a gateway,” but reiterates that “simply having an advantageous location doesn’t mean that investors would come to Sri Lanka, to set up operations. You have to provide a compelling story, and tell them why they should come and do business here.”

Meanwhile, on the topic of tapping into the island’s extensive finance and accounting talent, she recognises that the time is ripe for Sri Lanka to “choose its niche, and create its own value-addition space.”

Kasturi Chellaraja Wilson is equally unequivocal about her support for women in business, whilst also turning the spotlight on the need to promote female entrepreneurship at the grass-roots level.

While she acknowledges that “the organisational infrastructure is evolving, and has improved over the years,” Kasturi stresses that “organisational and HR policies cannot be too rigid, and have to accommodate women in the workforce.”

Q:How do you view the status of women in business, especially in the Sri Lankan context?

A There is an increased percentage of women working in the mid and entry levels of organisations, which is a direct result of the gender diversity you find among university graduates in the country, today. You don’t find gender discrimination to be an issue at the point of recruitment.

Within the junior ranks, among executives and non-executives, the percentage of women who want to be in the workforce ranges between 30 and 40 percent, depending on the industry. In the apparel industry, for example, this proportion could go up to 80 percent on the shop floor; but at corporate level, it tends to decline. So there is an issue.

Although corporates do a lot to encourage women to move up the ranks, practically from the middle management level upwards, career progression is less than ideal.

There’s a very low presence of women in senior management. The workplace tends to be a male-dominant environment; and unless one has grown with the organisation, women may find it tough to adjust. That’s not unique to Sri Lanka. In the global or regional context, too, the percentage of women in senior management is somewhat in line with the local reality.

Unless there’s a strong support system, you tend to grow your career at a huge personal cost. As a woman, you feel that sense of conflict in your mind. Generally, the middle management phase is also when you make major life choices.

The organisational infrastructure is evolving, and has improved over the years. In addition to offering flexi hours, you find corporates extending maternity leave up to six months, as opposed to the standard four months. It’s a signal that they want the employee to return to work; and it offers them a chance to take time with the transition, upon coming back. You also have companies offering crèche facilities and part-time work schedules, post the maternity leave period.

Organisations recognise that if they don’t attract the best talent to the workforce, and understand what it takes for these individuals to give their best and retain their services, they will drop out.

Women are smart enough not to abuse the system. So organisational and HR policies cannot be too rigid; they have to accommodate women in the workforce, to make sure their transition is smooth.

It also requires a cultural adjustment and shift of mindset at the broader societal level, to enable the role of the breadwinner to be shared between men and women, leading to a fulfilled lifestyle for all concerned.

Q: In which ways can more women look to enter the workforce, and progress to senior management positions?

A In the Sri Lankan context, female graduates of local universities still tend to be more timid and unsure about what they can bring to the table. They’re very capable, but tend to question themselves and what they can achieve.

There are exceptions; but the graduates who return from overseas are more open to change, and they are bolder and willing to take risks.

Therefore, it is imperative that the local education system ensures that a practical aspect is brought in, which provides candidates with the tools and confidence to come into the corporate world. Organisations are willing to be open, but it is a competitive environment.

On progression to senior management positions, mentoring should be part of the corporate system, where women can access support systems to pursue their careers and also manage their personal responsibilities.

Here, the biggest challenge a female would face is how much time she’d be willing to compromise from being a mum, and still feel fulfilled. Regardless of the choice, women who juggle multiple roles and pursue career progression would inevitably feel guilty about certain choices they make.

To progress in their careers, women need to learn to accept that they can’t manage all their roles effectively, unless they reach out for support. This support could be in the form of domestic aides, parents, spouse, work colleagues, secretaries, etc.

Q: Is female entrepreneurship – especially at the grass-roots level – duly recognised and rewarded in Sri Lanka, in your opinion?

A As far as I’m aware, there is no gender-specific support for women entrepreneurs at the grass-roots level. Pockets of the private sector are trying to make a difference. For instance, the Academy of Design has done a wonderful job of taking design to the grass-roots level.

There’s no formal method of recognising such individuals, but I consider Women in Management to be an association which does recognise women at the grass-roots level. Micro banking has also begun to evolve, with the likes of the Grameen model. This would facilitate the development of women entrepreneurs.

Q: Do you think it is right that we continue to encourage our women to work as domestic aides overseas, to support the national economy – i.e. through migrant worker remittances? How can this be changed?

A Morally, I wouldn’t want to see Sri Lankan workers being sent out to work like that. But in a more practical sense, they do generate foreign remittances – and as a result, their families lead an uplifted lifestyle. If we, as a country, cannot afford the same earning capacities for them in Sri Lanka, we can’t discourage them from venturing overseas.

Especially given the frequent incidents of abuse overseas, the Government should create a framework to safeguard our citizens who venture abroad in search of such employment. The Foreign Ministry must have a process whereby Sri Lankan workers are guaranteed a decent minimum wage, and are protected and not exploited.

When economic activity increases, and there are more job opportunities, our women who work as domestic aides overseas would gladly return to the country. The sad reality is that they prop up the economy through their remittances, but the nation doesn’t do enough to protect them.

Q: What are the pros and cons of the logistics sector, at this point of time – and has Sri Lanka made the most of its potential to become a logistics hub for the region?

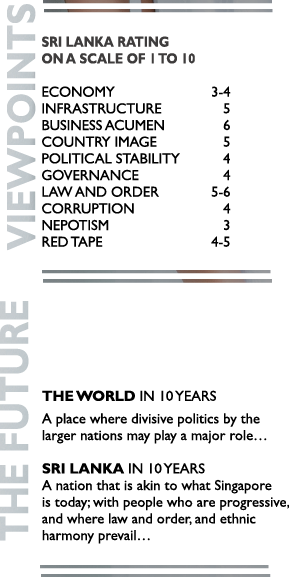

A We have not evolved; and we continue to be very traditional, in terms of logistics.

If you were to compare Sri Lanka with Singapore or Hong Kong, we have not evolved in terms of solutions and adapting technology, in the general sense of logistics.

But in the apparel industry, due to competition, and pressure on the supply chain and margins, manufacturing companies have pushed logistics solution providers to come up with innovative solutions.

We lack the infrastructure; and we’re quite traditional, by nature. But certain aspects are changing. Domestic manufacturing has evolved, and there seems to be a preference to outsource logistics. This provides an opportunity for logistics companies to think differently, and come up with innovative solutions.

Sri Lanka is a relatively small nation, but is in a position to become a logistics hub for the region and act as a gateway. But sadly, every government – even whilst recognising the fact – has not succeeded in facilitating this, so that external customers understand what they can do and what the benefit is of coming here. Simply having an advantageous location doesn’t mean that investors would come to Sri Lanka, to set up operations.

You have to provide a compelling story, and tell them why they should do business here.

There are different regulatory bodies, ranging from the Board of Investment (BOI) to the Ministry of Finance, Inland Revenue Department, and Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development as well.

I hope that the Megapolis will have a single framework that permits foreign investors to come in and work seamlessly in Sri Lanka – and create value for themselves, without encountering too much red tape and complicated processes.

What the Government is trying to do now is to come up with a framework whereby people can submit proposals. It is receiving inputs from the sector, in terms of what we require. So something is happening… but it is not happening consistently.

If we’re a hub, there’s ample competition out there. With global trade slowing down, what is the unique value proposition Sri Lanka would offer, in terms of infrastructure and investment relief, to encourage investors to divert their attention from another hub?

Q: Is there scope for value addition, in our port and aviation services – and if so, what would this entail and who should the torchbearers be?

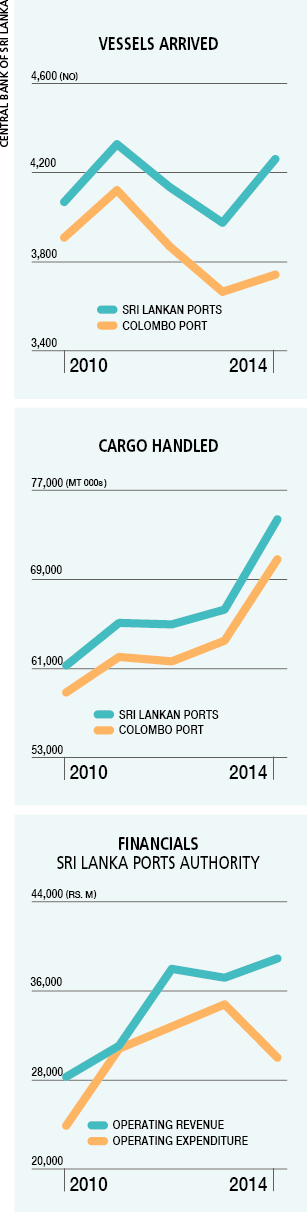

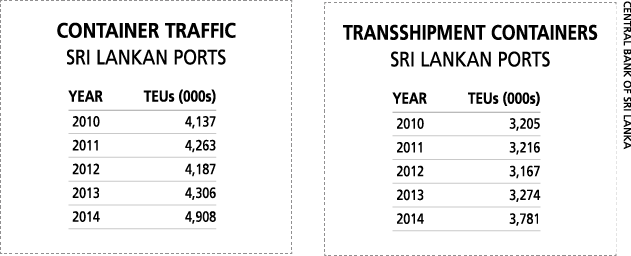

A At the Colombo port, thanks to the private terminals and other investments, we have three terminals – i.e. there are three independent terminals, with the Port of Colombo being the landlord. Ours is an import-dependent country, but the majority of traffic is in transhipment.

Having a deep-water port, in terms of CICT, you find even the mega vessels calling at Sri Lanka, since it has the only deep-water terminal in South Asia. This gives us a competitive advantage, for the time being.

However, as with any sector or industry, this would not remain a competitive advantage for too long, since the Government of India is looking at the development of Indian ports as a focus area.

To leverage on our current advantage, Sri Lanka needs to market itself as the Port of Colombo, and operate as the Port of Colombo. We need to move beyond individual terminals. And this would require strategic thinking and altering the present operating model.

Currently, the Government acts as both the landlord and a terminal operator, which lends itself to occasional dysfunction at the port.

If you were to consider how Singapore or Hong Kong works, the terminals are privatised and the landlord acts as an operator, where it encourages ships to call at the port. But in the Sri Lankan scenario, we find liners going to multiple terminals in Colombo, just to pick up boxes. This leads to practical inefficiencies.

To be a logistics hub, a country must have an aviation sector that complements its maritime trade. In the case of Sri Lanka, the volumes are not on the same scale as Singapore or Dubai, so there needs to be more investment in capacity, in addition to the terminal on the passenger and air cargo side.

Q: How would you assess human resources in the local logistics sector – viz. skills, talent, productivity, staying power, etc.?

A Locally, educational institutions such as the Moratuwa University have recognised logistics degrees. In addition, CINEC (Colombo International Nautical & Engineering College) has also introduced a supply chain and logistics degree.

As the private sector, we should support educational institutions and open our doors for undergraduates to intern from their second year onwards. This would equip them to add more value to their eventual employers.

Logistics has been a very traditional trade, and the people who have been in it for a long time are those who moved up the ranks. Where the middle and senior management is concerned, they might find it difficult to reinvent themselves.

Hence, we’re trying to find young, talented graduates who find adapting to technology much easier, and have the ability to create solutions and encourage us to change.

The dilemma is this: How do these young professionals become leaders for the future of logistics? That’s the crossroads that logistics companies are now encountering.

Q: Likewise, in your chosen field of accountancy, how capable are we (collectively); and is enough being done to unleash our potential in the BPO and KPO sectors?

A I don’t think we’re doing enough. We have a large pool of accounting talent; but it is limited, in terms of having a huge BPO play.

We should better position ourselves in the KPO field. Our professional accountancy qualifications are very aligned with UK and global accounting standards. But we don’t seem to be adequately leveraging on this strength.

SLASSCOM (Sri Lanka Association for Software and Services Companies) is doing a lot to promote outsourcing; but in the accounting, medical and legal fields, we could do much more, especially to position ourselves for KPO.

Sri Lanka needs to choose its niche, and create its own value-addition space.

We should aim for the low-volume, high-pay category of outsourcing work.

Q: Would you agree that there continues to be a lack of consistency in policymaking, and that allegations of ongoing corruption and nepotism in many sectors in our land are discouraging investors?

A The main deterrent is the lack of policy consistency, in general. For example, the retrospective taxes announced last year were a huge ‘no,’ in terms of attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Foreign companies wouldn’t be comfortable investing large sums of money, if they are not sure of the long-term prospects of doing business in Sri Lanka. That uncertainty, in itself, is a huge deterrent. So the biggest issue is the lack of consistency in policy.

Q: Could you describe the impact that large-scale infrastructure development projects (e.g. Colombo Port City, the planned Megapolis) are likely to have on the logistics sector – and indeed, the nation – going forward?

A These will impact the economy in the larger sense. It is necessary to invest in infrastructure to witness economic activity and progressive development in the future.

In any infrastructure development, there would initially be a logistics play, in movement, sourcing and the traditional logistics space. Financial services and industrials should grow, lending themselves to innovative logistics.

The Port City would be more of an economic hub, and lend itself to economic and industrial activity. Colombo could be viewed as a commercial and economic hub for the region. With that, the second aspect of logistics would kick in, in terms of solutions, upskilling staff, and the use of technology and innovation.

Q: What measures are needed to groom talent for the logistics sector’s future development? And where does Generation Y fit into the scheme of things, from a talent and HR point of view?

A Gen Y would come with a clean slate into the business, with no preconceived ideas of how logistics should be. They should adapt to technology, make it more open and come up with very innovative solutions.

Today, logistics is seamless. So how do you make it cheaper and faster for the consumer, and increase margins for the manufacturer? On the aspect of grooming talent for this space, there needs to be greater exposure to best practices.

Q: Looking ahead, what is your vision for Sri Lanka’s logistics trade?

A I wish we could become a trading hub, where the world would say we have competent people and no shortage of technology.

We should evolve into a technology solutions-driven logistics sector, where people are also empowered to think, and operations are seamless and efficient.

But it won’t be easy, as there’s a lot of change involved.