COVER STORY

Shaping a Sustainable Sri Lanka

Tamara Rebeira explores Sri Lanka’s transition to a green-blue economy

An island that is blessed with an abundance of pristine beaches and rich biodiversity is at long last taking heed of the importance of the green-blue economy – and seemingly transitioning towards it.

This concept combines both principles and promotes sustainable economic development, by integrating the sustainable use of marine resources (blue) with the conservation and preservation of natural resources and ecosystems (green).

It seeks to integrate these two factors to create a more holistic approach to economic development.

By tapping into the potential of marine resources, adopting renewable energy, preserving biodiversity and encouraging sustainable agriculture, Sri Lanka may be able to forge a path towards a greener and more prosperous future.

Embracing a green-blue economy not only serves as an investment in the future but also a commitment to protect the natural beauty and resoures that Sri Lanka is blessed with.

The green economy encompasses the development and adoption of environmentally-friendly technologies, processes and practices. It drives eficiency improvements, reduces pollution and promotes the sustainable use of resources.

Meanwhile, the blue economy hinges on connecting the potential of the ocean and its resources in a sustainable manner. It includes activities such as sustainable fisheries, coastal tourism, renewable energy generation and marine biotechnology.

A central pillar of this concept is the promotion of renewable energy sources and innovation. Sri Lanka can reduce carbon emissions and help mitigate climate change through the use of solar, wind and hydropower generation, and by investing in clean energy infrastructure.

The agriculture sector is another pivotal pillar; it serves as a foundation for sustainable food production, prioritising practices that minimise environmental impacts and ensure long-term food security.

To put this concept into practice and achieve economic growth, the government, businesses, communities and the public must work together, to ensure that the principles of sustainability, equity and resilience are met.

Responsible waste management is another cornerstone of sustainability. Daniel Knapp introduced the concept of zero waste in the 1980s, paving the way for the widespread adoption of recycling as a common practice. Today, the simple act of segregating waste in our households has become familiar to us all.

Recycling is recognised as an essential component of sustainable living that’s integrated into waste management systems worldwide. By embracing responsible waste management practices, we can minimise waste generation, promote recycling and contribute to a circular economy model.

On a separate note, the government’s expectation of moving towards green finance was announced in Budget 2023. The vision was for funds gained through such bond issues to be used for renewable energy, energy efficiency, green buildings, clean transportation, sustainable water and wastewater management, and pollution prevention among others.

The country’s endeavours to transition to a blue economy are in strong alignment with global initiatives such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) and Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030).

Meanwhile, the minister of trade recently stated that a framework has been drawn up to sell green and blue bonds while the cabinet approved a decision to obtain a second party opinion on this move.

The minister noted that green bonds can be used to raise funds for renewable energy, green buildings, clean transport, sustainable water supply, tackle climate change, protect biodiversity and the environment while blue bonds would relate to marine environment improvement activities.

Moreover, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has announced that it’s considering further concessionary funding and support for green bond issues as part of helping Sri Lanka recover from one of the worst economic crises in decades.

Chen Chen – who was the ADB’s Sri Lanka Country Director until the end of June – said steps are underway to prepare the groundwork to sell green or blue bonds after economic stability is restored.

Furthermore, the EU and Expertise France signed an agreement to set up a Green Policy Dialogue Facility (GPDF) to support the country’s ambition of developing a green and circular economy.

Along these lines, President Ranil Wickremesinghe recently stated that Sri Lanka needs fresh legislation to establish itself as a green economy – and as such, several new laws will be introduced this year.

In another progressive step, the Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE) introduced the listing and trading of green bonds for the first time on the stock market in April.

Embracing a green-blue economy not only serves as an investment in the future but also a commitment to protect the natural beauty and resources that Sri Lanka is blessed with

Commenting on the move, the CSE’s CEO Rajeeva Bandaranaike said: “As of January 2023, green bonds have globally raised US$ 2.5 trillion to support green and sustainable projects. Sri Lanka can tap into these funds and capitalise on [them] by attracting foreign investments into green bonds.”

Sri Lanka’s commitment to global sustainability objectives not only underscores its dedication to preserving the planet but also positions the country as an active contributor to tackling urgent environmental challenges on a world scale.

The emphasis on transitioning to a green-blue economy exemplifies Sri Lanka’s proactive stance in harmonising economic growth with environmental sustainability.

LMD’s green-blue special 29th anniversary edition highlights the significance of a sustainable Sri Lanka and sheds some light on the transformative potential of practices that have sustainability at their core.

By embracing this holistic approach, we can pave the way for a greener and more prosperous future, while inspiring others to follow suit in building a sustainable and resilient world.

Nature to the Rescue

LMD’s panel discussion on World Environment Day – moderated by Ruwandi Perera – focussed on nature-based solutions that can enable Sri Lanka’s economy to prosper with purpose.

The programme featured the CEO and founder of Good Life X – Randhula de Silva; the Co-Founder and Director of the Centre for a Smart Future (CSF) – Anushka Wijesinghe; Senior Advisor to Biodiversity Sri Lanka, President of the Institute of Environmental Professionals Sri Lanka (IEPSL), former Country Representative of IUCN Sri Lanka and former Head of the Regional Business and Biodiversity programme of IUCN Asia – Shiranee Yasaratne; and the founder of RETRACE Hospitality – Chalana Perera.

We reproduce edited excerpts of this panel discussion…

Ruwandi Perera (RP): What is the definition of nature-based solutions in a Sri Lankan context?

Shiranee Yasaratne (SY): Nature-based solutions come from and are inspired by nature. This has come into focus more recently and Sri Lanka has living examples of them.

For example, going back to the Asian tsunami, wherever we had mangrove systems along the coastal belt, villagers and communities were reasonably safe from the waves. This was because the mangroves acted as a barrier. Coral reefs do the same.

Another example is reforestation. When you reforest, the trees sequester carbon.

These are the examples we have here in Sri Lanka, and should be replicated and taken forward in a systematic and sustainable manner.

Chalana Perera (CP): Nature-based solutions are all around us and they’re a large part of the global economy. Although the Sri Lankan economy has been built from nature, it’s been done so in an extractive manner.

When we talk about nature-based solutions today, we refer to those taken from and given back to nature. It means regenerating natural resources that we’ve been exploiting.

So in a modern sense, nature-based solutions are influencing or inspiring design. Look at biomimicry design or biophilic design where a lot of R&D across industries and sectors has been based on extracting from nature.

In the case of tourism, our product is our biodiversity. So if we’re concerned about harnessing our biodiversity effectively, we have to regenerate our ecosystems to ensure we attract the high value tourism we’re aiming for.

Every sector in the country is linked to nature-based solutions because they are powered by human capital. We’re a result of what we eat and how we spend our free time, and all of that is linked to biodiversity.

RP: Anushka, why do we need to invest in nature-based solutions?

Anushka Wijesinghe (AW): Economists, and those in charge of economic growth and development, have done a poor job of thinking about the role of nature in the economy.

The metric that we often talked about growth is GDP. It’s one of the most outdated measures of economic growth and prosperity because you can add to GDP by degrading the environment.

You pay the price by having plastic bottles in the ocean. The more you add, it adds to GDP.

We have a fundamental problem with how we value nature, how that value is captured, and the means used to consider and measure economic growth.

It’s well-established that we need to consider nature and natural capital to be key components of our economy. We have the more fundamental challenge of putting nature and perhaps nature-based solutions at the heart of how we grow the economy, how we think about economic growth, our conception of development and what our priorities are.

Currently, all countries – including developing nations – are doing it right to varying degrees. In some countries – particularly Scandinavian countries – they’ve gotten a lot better at truly integrating nature into the economy. They not only see built capital as a growth driver but also natural capital.

There are countries in the Global South such as Costa Rica that are standard examples.

In many instances, this is being driven by young people and folks with new ideas are being allowed to come to the fore. That’s the challenge in Sri Lanka. Our development paradigm tends to be dominated by traditional thinking and older people. But fortunately, that’s changing.

RP: Randhula, how can we take nature-based solutions to a new level especially when catering to global markets?

Randhula de Silva (RS): We need to change our perspective of how we see ourselves – and what we see when we look inwards.

What do we see in Sri Lanka when we look inward and talk about our natural resources that are in abundance… and what do they mean?

For some, it can simply mean that our resources are commodities that can be exported. This has been the case for many years and we need to change that perspective.

Even though Sri Lanka has been blessed with abundant resources and in spite of the continuous extraction, nature keeps replenishing our rich and fertile ecosystems. However, we can’t keep going like this.

We must course correct how we work with our nature-based resources and how we convert them to build solutions, and share them with the world. So we need to regenerate and replenish what we have because soon, consumers will reject every extractive

practice.

During some recent work at the Lost Ingredients Lab, a young tech-based entrepreneur asked why we were working on jackfruit and gotukola. The value of what we have in Sri Lanka and what it means to the world needs to be viewed and understood locally first, through a regenerative lens.

This will help nature-based resources and solutions derived from them to be holistic, and be useful to both local communities and global consumers.

Many young people are coming back to Sri Lanka; and several who are in Sri Lanka have fresh perspectives, and they’re helping to shift the narrative.

RP: Shiranee, in terms of high value tourism, how can we offer something great at a reasonable price without enduring negative repercussions?

SY: Sri Lanka has huge tourism potential where nature is concerned but we haven’t taken that very seriously. When we visit other countries, we see how they use their natural resources to their advantage.

Fortunately, some of our higher end tourism chains have realised this. I’ve been working with a biodiversity private sector oriented platform and the tourism industry works very closely with us.

The concept is nature-based, and these chains try to market Sri Lanka’s culture, beauty and society together in a package. That’s the kind of thing that we should be looking at.

SMEs are part of the value chain. Our larger chains have realised the selling potential of ethical tourism and we should focus on SMEs. They need to be brought on board and allowed to learn from the many examples that are available.

Meanwhile, the Sri Lankan government is also serious about the policies being established. For example, we have the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which aims to enhance the island’s biodiversity.

When we say that we’re a biodiversity hotspot, it means that our biodiversity is reducing drastically. So we need to bring it back to the glory days using the policy documentation and action plan that’s been developed.

One of our nationally determined contributions (NDC) under the Paris Agreement looks to increase the island’s forest cover to 32 percent. Therefore, we need to convert the policies into action and encourage all stakeholders to act accordingly.

It’s not only the state that has such a responsibility; all Sri Lankans must be responsible and work towards achieving these NDCs.

RP: How are we faring in terms of our climate targets?

SY: Many private sector organisations are trying to achieve net zero status. Since this is an important goal for them, they are implementing a host of actions to become more energy efficient. But not many are looking at activities that are unrelated to their work such as sequestering carbon or restoring forests.

Renewable energy is extremely important in today’s context and many businesses are trying to minimise their use of fuel-based energy.

I’m observing a positive trend. But Sri Lanka is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and this is evident even in changing monsoon patterns. We must be ready with mitigation activities and solutions.

This is where nature-based solutions can play a role because they will help communities build resilience against the impacts of climate change.

RP: Anushka, do you share this optimism?

AW: We have to be optimistic because otherwise, we won’t achieve anything.

We can’t separate climate targets from a country’s larger development goals and the ambitions of people for prosperity. That’s why it’s necessary to build a nexus between nature, society, business and government.

If we don’t do that, we’ll continue to have a compartmentalised approach to mitigating the impacts of climate change.

The environment underpins everything we do – including how we grow the economy and climate ambitions such as renewables, reforestation and so on. There are examples where reforestation or replanting around rainforest borders has been undertaken with communities so that projects are sustainable as opposed to simply dropping plants in a disorganised manner.

Meanwhile, other organisations have not involved neighbouring communities, and implemented mangrove projects by simply planting new plants and hoping for the best.

There’s also talk about electrical vehicles (EVs) and going electric in our transport system. These well-intentioned plans are designed to completely electrify our three-wheeler fleet… but without understanding where the power is going to come from. We’ll still have to use electricity.

Climate ambitions should tie up with social realities and development goals.

While I do share the optimism, I worry that we’ll continue to think in silos and not understand how climate ambitious projects link with one another. We shouldn’t imagine that we can implement various projects such as electric mobility, reforestation or ecotourism in isolation.

So while we move forward, it is necessary to integrate all our projects and ambitions with the overall development of the country.

RP: So what are your views on climate ambitions? And how can we break the cycle of ad hoc project implementation?

RS: It’s important when we go micro at an organisational level to not simply look at restoration, conservation or meeting net zero targets as ticking boxes because they appear impressive to stakeholders and consumers.

But if you can transform the way you work as an organisation, it will improve the wellbeing of your community and the environment since your business is a part of a larger ecosystem. This process doesn’t refer to charitable efforts but rather, working for profit while taking nature into account as yet another stakeholder.

It’s a shift in perspectives and companies need to internalise these issues without viewing them as external things that need a solution. Otherwise, you end up working alone and not treating the solutions as part of a holistic process in a connected system.

Working in silos is happening at both the micro and national levels. The way to change this situation is by transforming how an organisation operates – after understanding why it exists.

SY: The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) play a very important role in this process because they integrate the gamut of sustainability needed for Sri Lanka to become a sustainable nation.

Where biodiversity or the environment is concerned, our life on land, beneath the water and climate action require people and nations to work in partnership.

This is why we’re trying to encourage companies to report on SDGs because Sri Lanka as a nation is reporting its progress in achieving them.

It’s only when businesses realise that they also contribute to the national conservation agenda that they’ll understand the depth and value of their contributions. So ad hoc projects like planting trees in a mangrove or forest do not contribute significantly to the national contribution unless they’re part of a larger whole.

CP: Regardless of the sector or industry an organisation belongs to, it’s about recognising that nature is at the core of all businesses. When that happens, there will no longer be a need for a sustainability department.

We have the brains, know-how, talent and passion; it’s the recognition that’s missing. World Environment Day should not be one day of the year but every single day.

RP: Randhula, are there any stakeholders who need to play a bigger role in the effort to protect the environment?

RS: Our generation and those to come will have to take up the challenge of protecting the environment. Millennials and Gen Z are conscious about the need for sustainability, and unwilling to let the status quo of extraction from nature continue.

It’s tough for millennials because they’re caught in the transition without having been born into it. I decided to remain in Sri Lanka and work towards enabling this process by engaging with both old and new players.

Everyone must be involved; no one can be left behind. It’s about transitioning to a new green economy that we can all embrace soon. And it’s becoming evident that the old era is over and a new dawn is breaking.

For the birth of a new era, there needs to be a change of perspective in the economic, financial, ecological and business spheres, and those who can grasp that transition are the younger generation.

They are not necessarily sitting in boardrooms. But they’re already on the field and ground, and working with communities, and rolling up their sleeves and doing the work. Now these new ideas, fresh perspectives and boundless energy must enter the boardrooms and places where policy is made so that the necessary conversations can begin to take place.

It’s only then that the shift will begin to gather momentum and society will be able to witness the transition.

Corporates have a huge role to play in Sri Lanka and many of the changes that we have seen in the past were led by the private sector, which includes both large organisations and SMEs. These enterprises are trying to make that shift happen and the government is introducing policies that create an enabling environment.

SY: Most of the landmass in Sri Lanka belongs to the state. And if the private sector wanted to do something in areas protected by legislation, it was difficult to obtain permission because corporates were viewed with a great deal of suspicion.

But today, the trend is changing and the younger generation working in those offices understands that it is necessary to view environmental protection through a holistic lens. The government has very little resources to do anything constructive and environmental restoration requires financing by the private sector.

AW: Like the other panellists, I am a firm believer that private sector entrepreneurs, however small or large, have the capacity to make innovative changes happen. But we have to be mindful of the fundamental role that the state plays and shouldn’t allow it to abdicate its responsibility nor overstep it.

We need to re-prioritise and realign the role of the state in all this and do the same with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka since it is the regulator that ensures financial stability.

A main source of instability is environmental instability. We may have well-regulated financial systems and effective policies, but we’re going to have immense climate and environmental instability… and the result will be social unrest.

Sri Lanka has some excellent pieces of legislation and regulations on environmental protection, and they have been around for decades – far longer than in many other countries.

RP: Anushka, how will instruments such as green bonds be game changers?

AW: Green and sustainable finance is going to be a huge part of our financial landscape over the next few years.

At an institutional level, some banks are attracting finance from greener sources. The government is considering a green bond framework at a sovereign instrument level, and we have global capital and plenty of offers of new capital that’s looking to deploy in countries like ours – for conservation efforts and so on.

In Sri Lanka, we have an abundance of potential projects that are ready to tap into this capital but the intermediation is still a little weak. Furthermore, we have the private sector and institutions that are still coming out of the CSR mindset.

Organisations need to understand that green finance isn’t simply about reforestation or conservation. It has to be at the core of the business. These monies must be used in sectors such as agriculture or tourism, which embody regenerative practices.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka needs to tell its story to the world, and explain what kind of projects exist and the types of investments that are required. Banks must play a key role in securing green financing for use in the conservation and restoration effort.

We still don’t place enough value on projects that adopt regenerative practices.

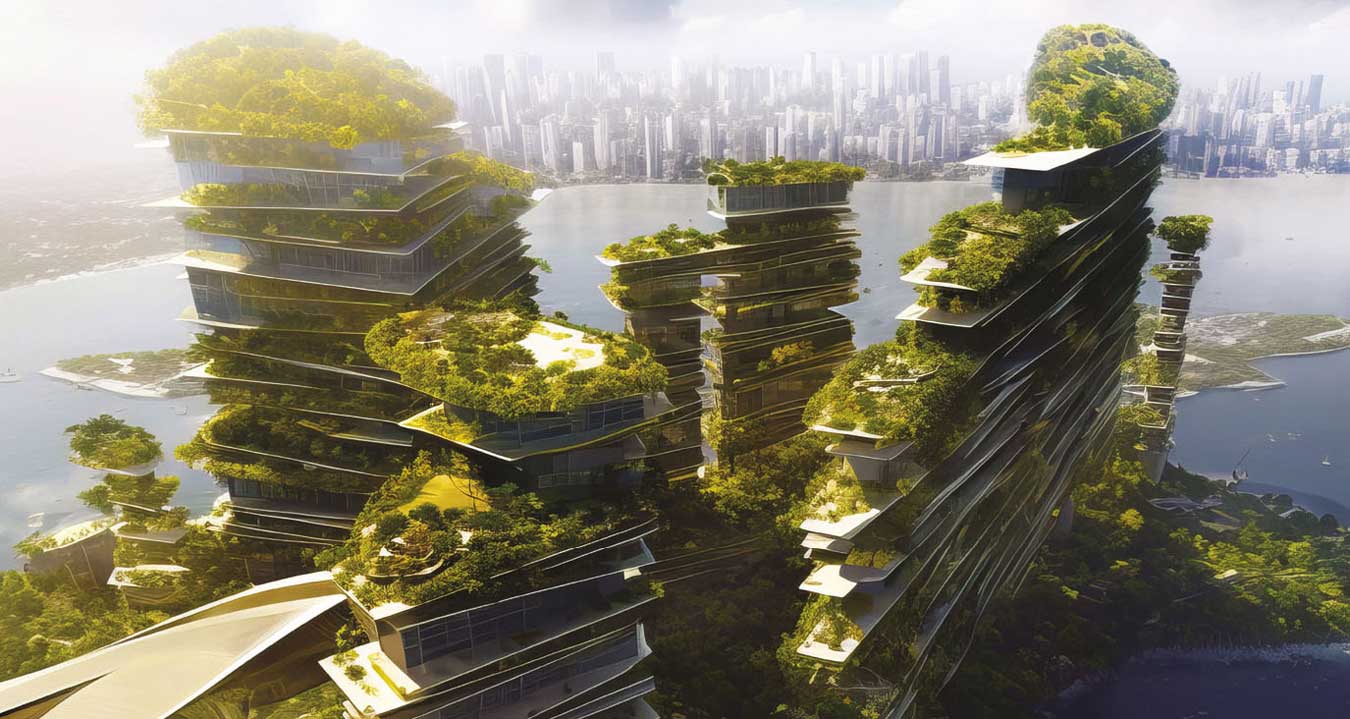

GREEN ARCHITECTURE

Building Sustainably

Murad Ismail unravels the workings of sustainable design and discusses the future of architecture

Q: Could you describe the concept of sustainable design? And what does it aim to accomplish?

A: Sustainable design aims to minimise adverse impacts on the Earth. As much as we talk about the environment, we must first recognise that there are eight billion people to accommodate. This is where environmental economics is factored in, weighing the pros and cons to provide for the population of the world with minimal damage to the planet.

There is a misconception that all environmentally-friendly materials are biodegradable. In reality, for a design to be eco-friendly, the materials must be able to withstand the test of time over the course of the lifetime of a product – i.e. if a building is made to last 100 years, the materials should be able to sustain itself for that period without requiring much maintenance.

We as an island nation need to obtain materials from diverse regions without depleting the surrounding resources to find suitable products

Principal Architect

MICD Associates

Environmentally responsible economics should involve considering the resources taken from the environment and the energy required to prpare them for building whilst comparing this to the amount of energy that they will provide in the form of durability.

If a building must last for 100 years, it’s pointless using materials that do so for only five years and need to be replaced or actively maintained to ensure longevity. Most products used to maintain materials contain chemicals that are harmful to the environment. In my opinion therefore, the only criteria for determining whether a substance is environmentally friendly should be the energy used to create it and that it will provide.

Energy utilised to operate a structure – be it electricity or water – is another part of sustainable design. Sustainable energy in this context would be nontraditional energy sources like solar and wind.

Even in this instance however, while enabling alternative energy sources, the scale of the structure (such as solar panels) needs to be taken into account. If a project is to be equipped with solar power, the solar farm would necessitate the destruction of a corresponding area of vegetation. Designs must take into account different strategies for using alternative sources of energy to power buildings without obliterating the environment’s chlorophyll count.

It’s important to factor actual vegetation and chlorophyll levels in sustainable design. To preserve the amount of chlorophyll in terms of carbon utilisation related to land use when a structure is developed on an acre of land, we must ensure that the greenery destroyed in this area is represented in its edifice.

Q: What role do you believe green building standards will serve in the future?

A: Green building standards go beyond materials and energy. In Sri Lanka, brick (considered to be an environmentally-friendly material) is made from clay collected from riverbanks, which leads to erosion. As such, to create environmentally-friendly materials, the environment is destroyed.

We need to be very careful in what we consider to be environment friendly. However, to achieve a carbon zero footprint, we must use materials that will last the lifespan of the building rather than expending resources to maintain short-lived products.

Looking at green certification – which mentions using materials within 1,000 kilometres of the site in addition to other requirements – it must be noted that while it’s nice to build using such materials, we as an island nation need to obtain materials from diverse regions without depleting the surrounding resources to find suitable products. Recycled materials such as plastic are truly acceptable as they are not discarded after serving their initial purpose.

On that note, the definition of ‘green building’ should be one that prevents long-term environmental damage. Green construction can use energy, chlorophyll and material choices to your advantage by wisely utilising the natural world.

Q: And what green technologies and eco-innovations are most likely to be used in the future?

A: In my opinion, the majority of commercial aspects will revolve around more modern and sustainable materials, energy sources and energy efficient machinery. But we must not deplete our greenery.

The ability to house eight billion people will result in the destruction of a substantial percentage of the Earth’s vegetation, notwithstanding the focus of the future on newer materials. This loss must be made up for on the constructed edifices.

It’s time for us as an island to actively work to replace chlorophyll on edifices since many East Asian nations are gradually implementing this idea in their architecture.

CONSERVATION ENDEAVOURS

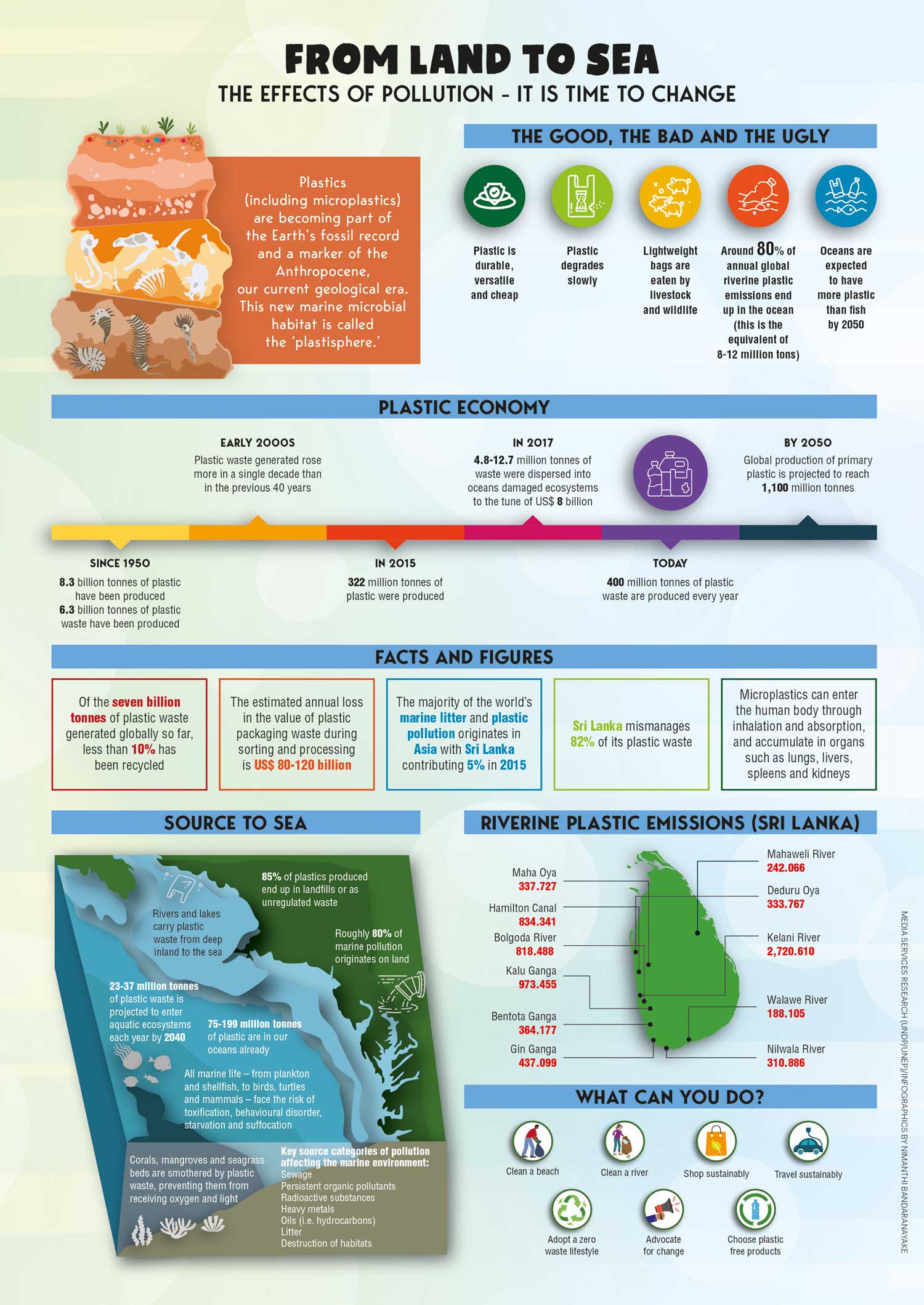

Ocean Watch

Lenin De Silva highlights the significance of the world’s marine ecosystems and our duty to preserve them

“Marine recreational fishing is known as a global leisure activity, and recognised for its cultural connectivity and economic importance,” notes Lenin De Silva, the President of the Marine Environment Conservation Society of Sri Lanka. However, he explains that the activity has both positive and negative impacts on marine ecosystems.

He points out that it can promote appreciation for the marine environment and encourage conservation efforts. Additionally, recreational fishing can contribute to local economies and provide livelihoods for many people.

As individuals, we can protect eco-systems by adopting sustainable practices as they collectively help maintain the health and balance of ecosystems

“But overfishing – particularly when vulnerable or slow growing species are targeted – can disrupt the balance of marine populations and ecosystems. It can lead to targeted fish stocks being depleted, in turn affecting species that depend on them for food or habitats,” De Silva maintains.

He notes: “Several activities are essential to reducing habitat damage, ranging from basic modifications such as increasing mesh eye size and size sorting grids to incorporating non-target species excluder devices and more importantly, monitoring, incorporating recreational fishing into fisheries policy management, planned stock assessments, data collection through collaborative actions and using the best scientific information available.”

Approximately 2.7 million people in Sri Lanka’s coastal communities depend on the fisheries sector for their livelihood, and 25 percent of the population are settled along the coastal belt while nearly 70 percent depend on fish as their primary protein intake.

But weather patterns affect fishing methods and fish availability, while factors such as illegal fishing, inequalities, user conflicts, outdated policies, overexploitation and insufficient governance jeopardise the food security of small island nations like Sri Lanka.

“Though it is not emphasised, our oceans hold most of the world’s biodiversity – especially coral reefs. They are directly connected to the global equilibrium of natural resources. Climate change disrupts ecosystems and alters habitats, leading to species distribution and abundance shifts. Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns can result in habitat loss and reduced resource availability for many species,” De Silva states.

He stresses that this can lead to declining populations, extinct species and disruptions in ecological interactions such that damage to tropical coral reefs, which support 25 percent of all marine species, could significantly limit the ocean’s diversity.

“As individuals, we can protect ecosystems by adopting sustainable practices as they collectively help maintain the health and balance of ecosystems, preserve biodiversity and mitigate the impacts of human activities on the environment,” De Silva concludes.

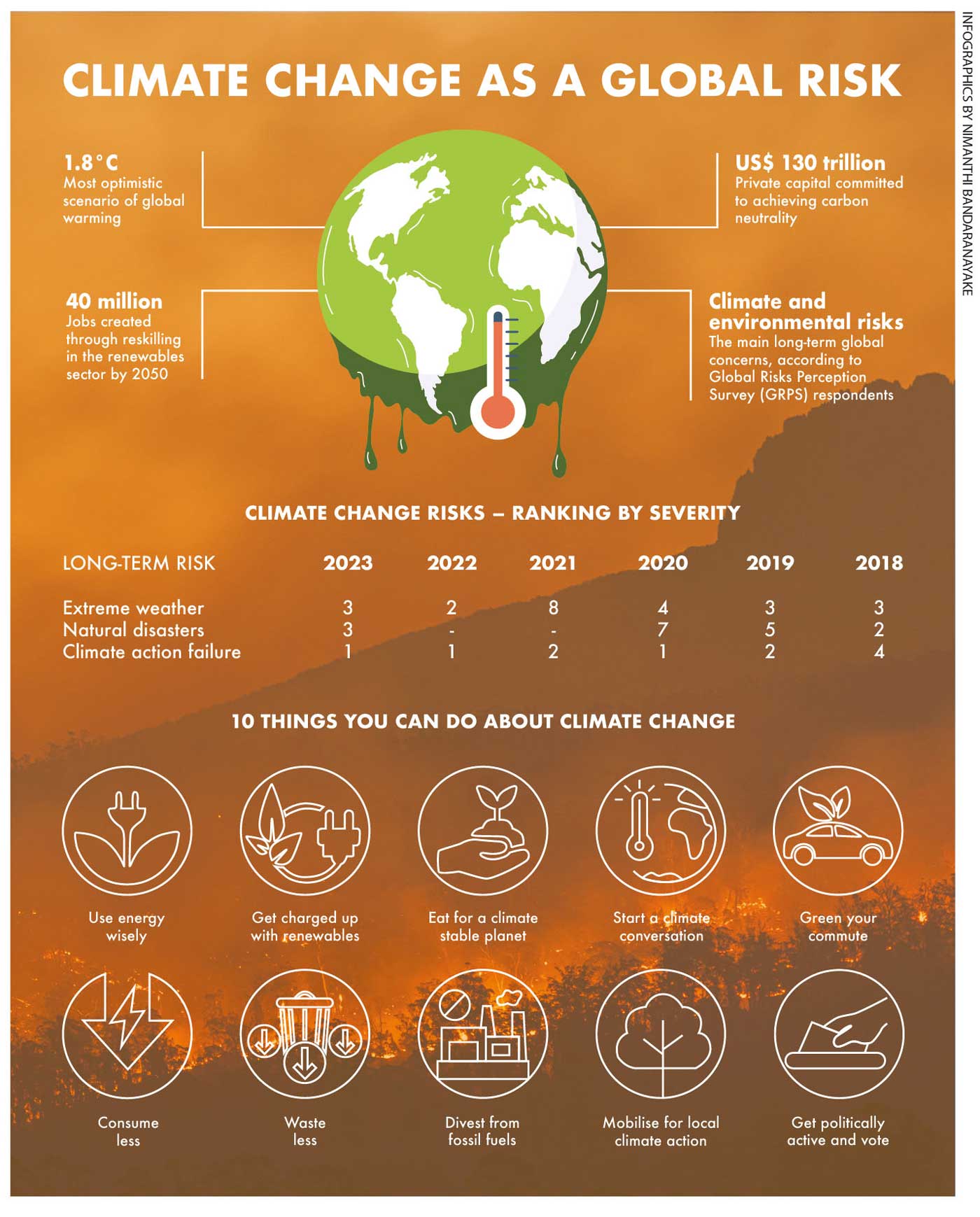

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climatic Catastrophe

Dona Senara and Nimanthi Bandaranayake analyse the impacts of climate change – and ways to mitigate them

Today’s rising global temperatures have evolved into a massive climate catastrophe that now threatens the survival of humankind. Climate change refers to the fluctuations in long-term patterns of weather conditions including temperature, humidity and rainfall.

Average weather conditions that were consistent over a period of at least 30 years have begun drastically shifting due to human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation. These have led to an increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and ultimately to the warming of the Earth’s climate.

Here’s an overview of today’s climate change status.

RISING TEMPERATURES The planet’s average temperature has already risen by about 1.1 °C since preindustrial times. If current emissions continue, this could rise to more than 1.5 °C in the next few decades.

MELTING ICE Each year, 750 billion tonnes of ice melt, contributing to the 24,000 tonnes of melted water being added to the world’s oceans every second. The main sources of melting ice are the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, and other glaciers.

RISING SEA LEVELS Since the beginning of the 20th century, sea levels have risen by about 20 cm and are projected to rise by another 30-110 cm by the end of the 21st century, depending on future greenhouse gas emissions.

WEATHER EVENTS Climate change is causing more frequent and intense extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, floods and hurricanes.

OCEAN ACIDIFICATION There is an ongoing decrease in pH levels in the Earth’s oceans as a result of increased absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Since the Industrial Revolution, the pH of the world’s oceans has decreased by about 0.1 units, representing a 30 percent increase in acidity that has a significant impact on marine life.

BIODIVERSITY LOSS Climate change is affecting ecosystems and causing a decline in biodiversity as species struggle to adapt to changing conditions.

IMPACTS ON HUMANS Climate change is affecting human health, livelihoods and food security. It disproportionately affects vulnerable communities including low income populations and indigenous peoples.

According to the UN, if Planet Earth is to preserve a habitable climate, emissions of greenhouse gases must be cut by half by 2030 and to net zero by 2050. Therefore, wide-ranging actions that are fast and effective need to be taken by governments, businesses and citizens. Activities focussed on climate change mitigation aim to reduce and prevent greenhouse gas emissions.

Moreover, they are designed to promote climate resilience and low emission strategies in countries.

Utilising new technologies and renewable energies, modifying equipment to be more energy efficient, and changing management practices and consumer behaviours, are some examples of mitigation activities.

Mitigating climate change offers those spearheading such initiatives new opportunities – particularly since strong sustainability strategies can help drive companies to new markets. Businesses are in a strong position to be the driving force against climate change.

Today’s rising global temperatures have evolved into a massive climate catastrophe that now threatens the survival of humankind

Working towards carbon neutrality is a meaningful way for businesses to mitigate climate change, and fostering innovation to develop sustainability strategies using renewable energy and waste management will enhance the process. And given the consumer demand for environmentally sustainable goods, businesses are in an ideal position to demand that their supply chains become carbon neutral.

Individual activities are another important aspect of helping this initiative. Reportedly, nearly two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions are linked to private households where a person’s power usage, food consumption, transportation modes and purchases add to his or her carbon footprint.

Shifting to eco-transport modes, minimising energy consumption, reducing food waste and adopting the 3R initiative (reduce, reuse and recycle) are a few actions that can reduce the individual carbon footprint, for a greener and safer planet.

The green-blue economy – if harnessed well – would greatly support Sri Lanka’s growth. However, this would need to be transparent and digitalised with long-term policies, for real benefits to translate into economic and social growth.

Anoka Abeyratne

Climate policy expert

Co-founder

Anticlimatic

As an island nation, Sri Lanka possesses tremendous potential for the development of both the green and blue economies. With its abundant resources, the country has the potential to become a global example in sustainable practices.

The green economy focusses on the sustainable use of natural resources to boost economic growth; the blue economy entails the responsible utilisation of ocean resources. With these opportunities – including sustainable tourism – Sri Lanka can foster economic development in an environmentally conscious manner.

Nishshanka De Silva

Founder

ZeroPlastic Movement

The green economy is a macroeconomic approach based on the principles of sustainability, resource efficiency and low carbon emissions. This is significant to Sri Lanka in the context of environmental conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, economic opportunities and job creation, energy security, resilience and risk reduction, and international cooperation and funding.

Dr. Chethika Gunasiri

Environmental Scientist

Sri Lanka Land Development Corporation (SLLDC)

At a time when the country is reeling from the aftereffects of unsustainable economic practices that were in noncompliance with the core characters of the nation, sustainable green and blue economic strategies will provide healthy and long-term growth to Sri Lanka.

Being an island nation where natural resources are not adequate for the ever increasing population, well planned blue and green economic strategies will provide security for these depleting resources, while enhancing the nation’s GDP growth through the protection and conservation of our environment and ecosystem.

Sri Lanka has the potential to expand its blue economy as its sea comprises a much larger space than the land area. Similar to many small island nations in the world excelling in blue economy strategies, Sri Lanka too can harness its ocean resources while conserving the increasingly threatened marine ecosystem.

This island has some of the largest seagrass areas in the world along with many varieties of mangroves. These serve to increase carbon sequestration in a world where growing carbon emissions are serving as a rapid avenue towards climate change.

Muditha Katuwawala

Coordinator

The Pearl Protectors

The green-blue economy revolves around promoting sustainable development by focussing on reducing carbon emissions, improving resource efficiency and fostering social inclusiveness.

This recognition of natural capital as an economic asset benefits not only the environment but also marginalised communities reliant on natural resources. It’s a vision that combines economic growth, environmental stewardship and social justice to transform our world for the better.

As an island nation, Sri Lanka has a valuable opportunity to embrace the blue economy, which complements the green economy by emphasising the sustainable utilisation and management of ocean resources.

The country’s diverse natural resources and expansive coastal waters make it a perfect candidate for embracing the green economy and achieving sustainable development.

Sri Lanka finds itself at a crucial point, aiming to achieve sustainable development and establish a responsible global presence. In this endeavour, sustainable finance and private capital have emerged as catalysts for change, presenting a distinct opportunity to tackle urgent environmental and social issues while fostering economic growth.

By incorporating sustainability principles into its financial systems and attracting private funds, Sri Lanka can explore fresh channels of investment, draw international capital, and cultivate a resilient and inclusive economy.

Such economies provide opportunities for economic growth, job creation and social development in local communities.

M. M. Hanan

Public Relations and Communications Coordinator

Biodiversity Sri Lanka

Given Sri Lanka’s historically abundant yet rapidly depleting natural resources, the adoption of a green economy could help strengthen our island’s position in the face of challenges that lie before us.

A green economy prioritises low carbon emissions, uses natural resources efficiently, is socially inclusive and prevents the loss of biodiversity. All these factors would contribute positively towards our country and its development.

Blessed with a wildlife rich protected area network, Sri Lanka’s terrestrial landscapes are capable of generating income exponentially if managed efficiently. For this to happen however, the relevant stakeholders need to unlock the true potential of the natural capital that we’re blessed with – rather than plundering it for short-term gains.

The time to adopt progressive strategies that prioritise the planet over profit is now!

Vinod Malwatte

Co-founder

The Parrotfish Collective

Leave a comment