COVER STORY

Growth Overture

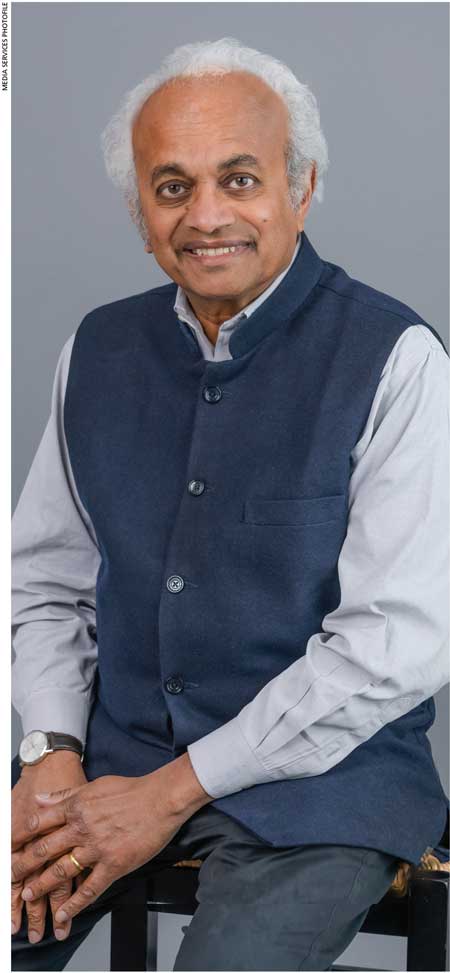

Prof. Shantayanan Devarajan is a distinguished figure in the fields of international development and economics. Born in Sri Lanka, he brings a unique perspective enriched by his cultural heritage and global academic exposure.

Devarajan’s multifaceted background coupled with academic excellence positions him as a leading figure in international development and economics.

He currently serves as a Professor of the Practice of International Development and the Chair of the International Development Concentration at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service.

In addition, Devarajan serves as a member of Sri Lanka’s presidential advisory group on debt restructuring and multilateral engagement.

Prior to his academic tenure at Georgetown, Devarajan dedicated 28 years to the World Bank, leaving an indelible mark as its Senior Director for Development Economics, and Chief Economist of the South Asia, Africa, and Middle East and North Africa regions, as well as the Human Development Network.

![Cut-2.mp4_snapshot_00.26_[2023.10.26_14.09.02]](https://lmd.lk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Cut-2.mp4_snapshot_00.26_2023.10.26_14.09.02.jpg)

Within the World Bank, he also served as Research Manager for Public Economics, harnessing his expertise in the intricacies of economic policy formulation.

Prior to his tenure at the World Bank, Devarajan was a faculty member at Harvard Kennedy School.

Devarajan’s scholarly endeavours include both authoring and co-authoring around 150 publications. His research spans diverse domains including public economics, trade policy, natural resources and environmental economics, political economy and general equilibrium modelling of developing countries.

In this exclusive interview, Devarajan emphasises the critical need for structural reforms aimed at addressing fiscal policy, corruption and public sector management issues.

– Compiled by Tamara Rebeira

The reason the tax hikes are hurting small businesses and the middle class is that large businesses and the upper class are not paying their share of taxes

Prof. Shantayanan Devarajan

Q: Sri Lanka’s economy has faced unprecedented setbacks in recent years. In your view, has there been progress in addressing the challenges we have faced?

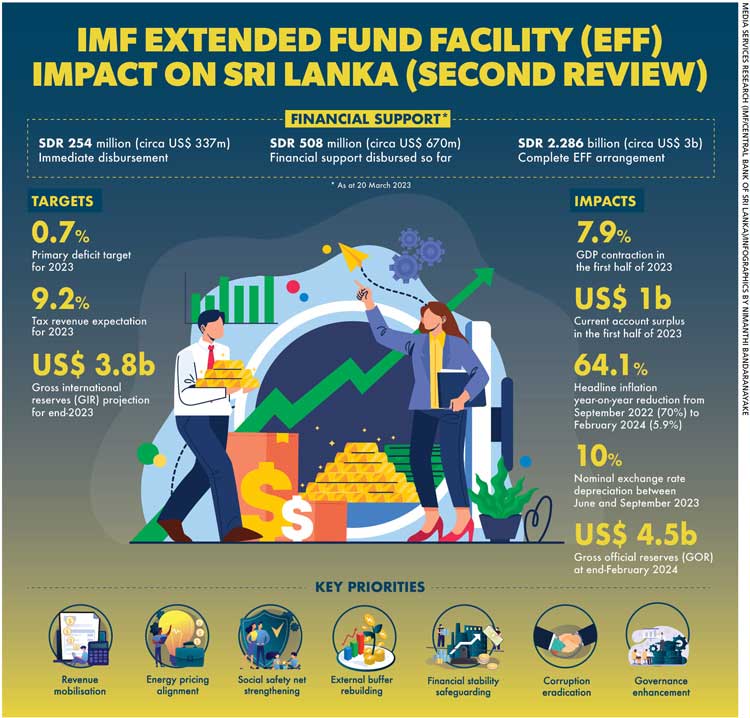

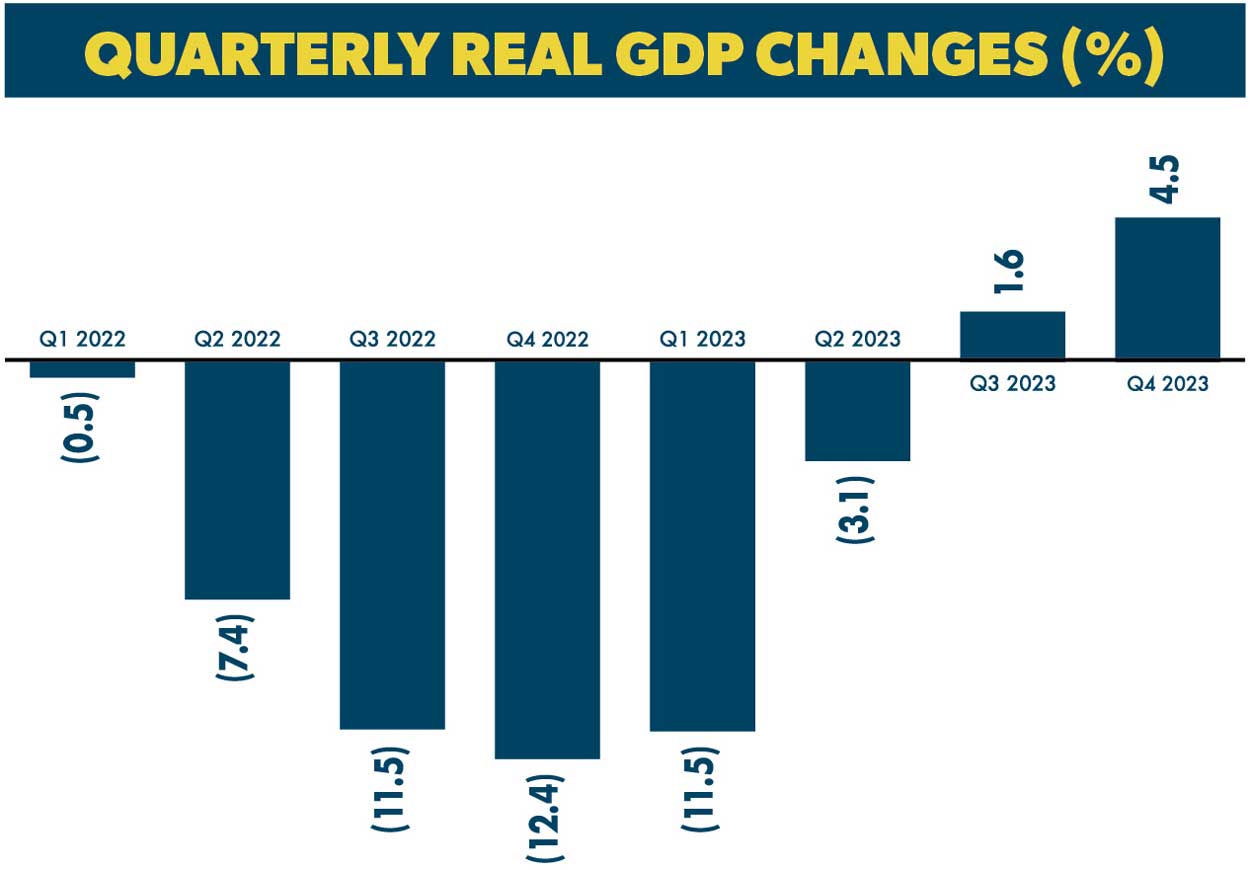

A: Certainly, there has been progress. Inflation has fallen from 70 percent to under six percent in around a year. Economic contraction, which was seven percent in 2022, improved to two percent last year and is expected to turn positive in 2024.

The long lines for fuel and food have disappeared. To be sure, a lot more needs to be done to resume growth, and make it inclusive and sustainable; but the progress since 2022 has been significant.

Q: In December last year, you stated that Sri Lanka will turn towards economic growth in 2024. Will we be able to stay on course given that there’s been growth in the third and fourth quarters of last year (1.6% and 4.5% respectively, following six consecutive quarters of contraction) – despite this being an election year?

A: The fact that growth was not only positive but accelerating during the last two quarters of 2023 bodes well for positive economic growth this year.

Of course, there are risks to this forecast but these are mainly due to global market conditions – e.g. high commodity and food prices, a slowdown in tourism and so on.

Elections by themselves are not a risk. But in some countries, governments resort to populist policies prior to an election, which may undermine growth in subsequent years.

In Ghana for instance, prior to all elections, the government increases civil servants’ salaries, widening the fiscal deficit and promptly leading to an IMF programme (this is less likely to happen this year as the country is already in an International Monetary Fund programme).

BACKGROUND

BIRTHDAY

27 April

FAMILY

Wife – Nancy Benjamin

Daughters – Sonali and Kumari

EDUCATION

S. Thomas’ Preparatory School

United Nations International School

International School of Geneva

QUALIFICATIONS

AB in mathematics – Princeton University

PhD in economics – University of California (Berkeley)

HOBBIES

Chess

Calligraphy

Cooking

Q: The IMF programme requires structural reforms in areas such as fiscal policy, corruption vulnerability and public sector management. How can we ensure that these reforms are implemented since not all of them have seen the light of day so far?

A: These reforms are necessary to put Sri Lanka on a path of sustained, inclusive growth.

For example, reforms of state owned enterprises are needed as they run huge deficits that deplete the Treasury and threaten the stability of the financial system – SriLankan Airlines’ debt alone is one percent of GDP.

The IMF’s governance diagnostic assessment identified the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) and Sri Lanka Customs as the most corrupt state institutions. This may explain why Sri Lanka’s tax collections are so low (around 9% of GDP).

It’s not surprising that there is resistance to these reforms as they constrain the discretionary power of government.

To ensure that these reforms are implemented, the public who stand to gain the most from them should raise their voice in support of such reforms – just as they did in support of good governance during the aragalaya in 2022.

Q: How do you view recent pronouncements by opposition parties implying that should they win at the polls, they’d review the conditions laid out in the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF) framework? And likewise, how would prospective investors view these statements?

A: The IMF supported economic reform programme has the potential to unite rather than divide the various parties contesting elections.

While the ruling party supports the reform programme, it is somewhat silent on governance reforms.

Opposition parties – especially the National People’s Power (NPP) – seem opposed to the economic reforms but strongly advocate for good governance.

However, the economic and governance reforms are two sides of the same coin.

For example, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act, which constrains the monetary authority’s financing of the fiscal deficit, could be seen as a standard prescription for prudent macroeconomic policy and low inflation. But it is also a step towards good governance.

By tying the hands of the financial regulator, the act makes it difficult for the Ministry of Finance to force the Central Bank of Sri Lanka to finance the fiscal deficit, reducing the incentive to run high fiscal deficits.

The reform of fuel and electricity subsidies to reflect costs – accompanied by targeted cash transfers to the poor to help pay for the higher cost of electricity and fuel – not only saves money but also makes the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) accountable to consumers – rather than the government. This will reduce the use of these subsidies for political patronage.

Meanwhile, the requirement that large procurement contracts be published will not only keep the size of these contracts down, which will help contain the fiscal deficit, but also diminish incentives for kickbacks and other side payments associated with procurement.

Finally, the structural condition that assets of public officials be disclosed will go a long way towards reducing corruption.

In summary, the components of the economic reform programme and efforts to strengthen governance in Sri Lanka are mutually reinforcing.

Elections by themselves are not a risk. But in some countries, governments resort to populist policies prior to an election, which may undermine growth in subsequent years

Q: Are there any particular policies or reforms that you believe should be prioritised to stabilise the economy and foster sustainable growth?

A: Since this is an election year, I would prioritise policies that are difficult to reverse and constrain government from reckless behaviour in the future.

With these criteria, my top four reforms are firstly, the Central Bank’s independence – tie the institution’s hands so that the finance ministry cannot demand that the fiscal deficit be financed by borrowing from the Central Bank.

Secondly is targeted cash transfers – reforming the Samurdhi programme and implementing Aswesuma in a manner that it cannot be manipulated by politicians trying to curry favour with their constituents, some of whom are not poor.

Thirdly, tax foreign investment. Most foreign investments come in free of tax – including future investments in Port City Colombo, for instance. There is no evidence that zero taxes encourage investment since most investors look for stability and not low taxes.

Moreover, given that middle class Sri Lankans are paying substantial taxes to finance public spending, it is time that these investors – who are not poor by any standards – also pay their fair share.

Ireland for example, has a single flat rate tax on all foreign investments and collects more tax revenue than any other country in the EU.

And finally, transparency – the publication of large procurement contracts and politicians’ public assets are a necessary part of the governance reforms in the country. As former US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said: “Sunlight is the best disinfectant.”

SRI LANKA TODAY

STRENGTHS

Educated and healthy population

Natural beauty

Strategic location

WEAKNESSES

Weak governance

Excessive government interference

in the economy

Macroeconomic instability

OPPORTUNITIES

High-tech sector

Tourism

Open trade

THREATS

Ethnic conflict

Political polarisation

Geopolitics (China vs India or the US)

Reforms of state owned enterprises are needed as they run huge deficits that deplete the Treasury and threaten the stability of the financial system – SriLankan Airlines’ debt alone is one percent of GDP

Q: President Ranil Wickremesinghe recently stated that Sri Lanka will finalise a debt restructuring framework within the first six months of this year. And he expressed confidence that the nation is recovering from its worst financial crisis in decades. Do you agree and is such an aspiration practical – and why or why not?

A: I would agree. There has already been an agreement in principle (AIP) with official creditors (China, India, Japan and so on).

In March, negotiations were ongoing between the Sri Lankan government and private creditors, which should result in a similar AIP in the weeks ahead. It usually takes around two months after these agreements for lawyers to work out the details so a target of June seems realistic.

The IMF’s governance diagnostic assessment identified the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) and Sri Lanka Customs as the most corrupt state institutions. This may explain why Sri Lanka’s tax collections are so low (around 9% of GDP)

Q: On a separate note, with elections approaching and given the multiple uncertainties that are bound to follow, how do you assess the sensitivities in the light of possible outcomes – and their impact on businesses and marginalised communities?

A: I assume you mean the uncertainty about the outcome of elections. But I don’t think this uncertainty is likely to affect economic outcomes.

First, as I said above, the various parties are fundamentally in agreement with the reform programme.

They may have differences in details but the main thrust of the programme – fiscal consolidation, greater openness, targeted cash transfers to the poor and transparency – is widely shared. I have determined this during discussions with opposition parliamentarians as well as and more recently, with the youth wings of various parties.

If the reform programme is sustained, its impact on businesses and marginalised communities will be favourable.

Q: Critics of the government say that populist measures are likely to be announced ahead of the forthcoming elections and they will derail the progress made in the last year or so. In your view, is it realistic to expect the government to stop short of offering relief to the people at such a time?

A: Yes, it is realistic. I think that the people of Sri Lanka have seen what happens when the government offers what seems like relief – such as the Rajapaksa tax cuts of 2019 – but eventually bankrupts the country and causes unprecedented hardship.

I don’t think they will allow the government to try something like that again.

The structural condition that assets of public officials be disclosed will go a long way towards reducing corruption

Q: The recent tax hikes were necessary but they’re hurting small businesses and the middle class as disposable incomes shrink. What choices, if any, do we have in this regard?

A: The reason the tax hikes are hurting small businesses and the middle class is that large businesses and the upper class are not paying their share of taxes.

Sri Lanka does not have a wealth tax even though we know there’s a lot of wealth in the country (wealth is typically much more unequally distributed than income).

If we can tax wealth, then the middle class would not have to pay as much in taxes. The fact that the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce seems opposed to returning to a Pay As You Earn (PAYE) system, which creates incentives for people to file tax returns, indicates the resistance among the upper class to paying their fair share of taxes.

As mentioned already, since most foreign investment comes in tax free, the working people of Sri Lanka have to pick up the slack.

GOVERNANCE

Q: How important are governance, transparency and accountability to the country’s development and economic performance?

A: It is the most important factor in the country’s development and economic performance. Not only does corruption lead to the misallocation of resources but it also leads to poor policies that undermine the performance of the entire economy.

REFORMS

Q: In your view, in which areas are policy reforms urgently needed to stimulate growth?

A: Tax reform (both in tax rates and collection); trade reform towards greater openness; and agricultural reform (e.g. reforming the Paddy

Lands Act to allow farmers to grow

the most lucrative crops).

Not only does corruption lead to the misallocation of resources but it also leads to poor policies that undermine the performance of the entire economy

Q: In the context of foreign direct investments (FDI), Sri Lanka is working towards attracting offshore investors for the likes of the Port City Colombo and renewable energy projects. What strategies do you recommend for improving the investment climate and attracting more foreign capital – and attracting quality investments?

A: Firstly, I would not recommend tax holidays.

Secondly and most importantly, is providing a stable macroeconomic environment – i.e. low fiscal deficits, current account deficits, inflation and debt, all of which are part of the IMF supported programme and debt restructuring programme.

Finally, I would recommend low (but positive) taxes at a flat rate with no exceptions – this minimises the opportunity for corruption and provides investors an assurance of the future business climate.

Q: As for the global economic environment, which has been under a cloud amid multiple wars and the impacts of climate change, where do you think we’re heading and what are the main sensitivities?

A: The global environment is highly uncertain with risks tilted to the downside. The Israel-Hamas war in Gaza could intensify and disrupt global value chains (as is already happening in the Red Sea); tensions between China and Taiwan could grow; the Russia-Ukraine war continues with its disruptions to world trade; Europe is in recession with higher than desirable inflation; the Chinese economy is slowing; and the US and China are engaged in a cold war.

Then there’s the increasing impact of climate change – droughts, floods and rising sea levels that affect large swaths of the planet.

GEOPOLITICS

Q: How do you assess the impact of geopolitical tensions and global economic uncertainties

on Sri Lanka’s economy?

A: They have an important effect.

For instance, geopolitical tensions between the US and China have delayed progress on debt restructuring. Global economic uncertainties affect Sri Lanka mainly through world interest rates and demand for Sri Lanka’s exports (including tourism), and disruptions in global supply chains.

There is no evidence that zero taxes encourage investment since most investors look for stability and not low taxes

Q: Sri Lanka is in the midst of a debilitating brain drain with many skilled professionals leaving the country in search of better prospects. How can the government play a part in talent retention?

A: I oppose the use of the term ‘brain drain,’ much more calling it debilitating. What is wrong with Sri Lankans finding better prospects in other countries? People have been doing this in all countries since time immemorial.

In the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankans secured jobs in the Middle East and improved their earnings.

In the Philippines, there is evidence that the possibility of finding better jobs overseas stimulates training of nurses, increasing the number of trained nurses in the country – a ‘brain gain.’ The fact that the government paid for the migrating workers’ education is neither here nor there.

A study of Nigerian doctors in the US and Canada showed that they send more money in remittances back to Nigeria than the cost of their education.

The reason why some are concerned with the recent migration of Sri Lankan doctors and engineers is that there seems to be a shortage of these professionals in the country. If so, there is a solution: allow doctors and engineers from other countries to work in Sri Lanka.

Many countries rely on migrant workers for their skilled labour (the Gulf States are a prime example). There is no reason why Sri Lanka, especially with its shrinking labour force (even without migration), should not do the same.

Geopolitical tensions between the US and China have delayed progress on debt restructuring

Leave a comment