STOP CORRUPTION

EXORCISE THE DEVIL!

BY Charmaine Fernando

The scale of corruption engulfing our little island has clearly supported the contention that we are a nation of rogues! A small consolation, perhaps, is that Sri Lanka has improved on its ranking in the Corruption Perceptions Index compiled by Transparency International – we were ranked 85th out of 175 countries, in the 2014 index, compared to a rating of 91 (out of 177 countries) the year before.

Corruption poses a serious development challenge to any society or nation. It destabilises democracy and good governance. At the same time, it undermines the legitimacy of government, and democratic values such as trust and tolerance.

THE RULE OF LAW Such appalling dishonesty in its varied forms also compromises the Rule of Law. And bribery, sleaze and fraud in public administration results in public services being inefficient – or inaccessible, to those of us who don’t ‘give’!

Corruption violates the basic principle of civic virtue. More generally, it erodes the institutional capacity of government, as procedures are disregarded, resources are siphoned off for personal use or gain, and public officers are bought and sold.

It’s no secret that many state institutions and businesses in Sri Lanka are plagued by corruption, which includes instances of blatant fraud, financial misappropriation, underutilised assets, deficiencies in tender procedures, management and operational inefficiencies, and sinful wastage.

Political life and government institutions are also bedevilled by cronyism and nepotism. Sadly, such disorder – combined with graft and kickbacks – do not appear to be dirty words in our phrase book anymore. Corruption has become a rapacious sub-culture. It has overwhelmingly become part of our national heritage.

COPE EXPOSURES Over many years, the Committee On Public Enterprises (COPE) – the nation’s parliamentary watchdog – has consistently exposed the staggering extent of losses as a result of the mismanagement, plunder and waste in far too many state-owned entities. COPE reports have regularly uncovered cases of gross mismanagement by public servants every year, but they’re ignored after the initial outrage wears off.

There is an outlandish quality about such corrupt behaviour that has eluded understanding and seems to demand further inquiry, because of allegations and the grave nature of the premeditation of the acts themselves. Through all this rank assortment of inequality and obtrusive embezzlement emerges the sordid picture of the beneficence bestowed on low-achievers, and the shameful nepotism that benefits inept and unsuitable lackeys and relatives.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE Despite the widespread phenomenon of illegal gains by public officials, Sri Lanka has still not enacted effective financial disclosure laws. While a 1975 law obliges high-ranking officials to submit annual declarations of their assets, they’re not independently audited. In fact, as of 2003, less than five percent of MPs had complied with the law.

Although failure to make the declaration is considered a criminal offence, violators are rarely punished. The plunder of state assets is carried out with a sense of impunity. And it is worth noting that no high-ranking official or politician has been prosecuted for corruption or abuse of power while serving in office.

ROBBING OUR YOUTH Worse still is the reality that this widespread pervasiveness of corruption is robbing our youth of their rightful inheritance. Corruption is insidious and corrosive, and the damage that it wreaks today will be felt well into the future – by those who played no part in it; or at least, are relatively free from blame.

What a disgraceful example of dishonesty we’ve set for future generations. Not all Sri Lankans will relish that shameful prospect of being tarnished with the same questionable brush. But we must accept being part of the gigantic swindle, unless we rise in a concerted effort to exorcise its demonic spread.

CRACKDOWN ON CORRUPTION

BY Zulfath Saheed

Sri Lanka is evidently a nation in transition, with political and economic reforms slow to take off but very much required, in the context of overall development. Alas, we often find our lawmakers distracted by internal party squabbles and partisan agendas, unable to see the forest for the trees, as it were.

So when a new President and Administration were voted and brought into power on 8 January, underpinned by the premise of ensuring ‘good governance,’ the people – and by extension, the economy – received a semblance of hope that the many alleged evils of Sri Lankan politics would be rooted out – or at the very least, that an honest attempt would be made to do so.

REALITY CHECK Yet, here we are, at the end of the Interim Government’s 100-day programme, with little to show in the form of actual results. The term ‘corruption’ has been thrown around on multiple occasions, but how far have we come in bringing the alleged perpetrators of such crimes to book?

Granted, a thorough investigation needs to be conducted to ascertain the full facts of each and every case. And while countless politicians from the previous regime have made their way to the Bribery Commission and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), to record their statements, very little detail is available on the outcome of such interrogations.

The Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption was established in as far back as 1994, to direct the institution of prosecutions for offences under the Bribery Act and the Declaration of Assets and Liabilities Law, No. 1 of 1975.

More recently, following the presidential election, the Government sought to appoint an Anti-Corruption Committee to probe large-scale corruption that allegedly took place during the tenure of the previous Administration. Cabinet approval was also granted to set up an Urgent Response Committee, consisting of public officials, police officers, lawyers, finance specialists and officials of the CID.

The short-term actions of the committee were to include investigating alleged corruption and irregularities at the Employees’ Provident Fund and Colombo Stock Exchange, while long-term actions were to cover the introduction of a more powerful Bribery or Corruption Commission; the establishment of a National Procurement Commission and obtaining approval for all projects through this commission; the introduction of a National Audit Act and implementation of the UN Anti-Corruption Covenant, for which Sri Lanka is a signatory.

ONE-SIDED HUNT In March, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe reportedly offered assurances of punishing all corrupt politicians and officials, under the 100-day programme – even going so far as to caution that if the Bribery Commission failed to punish those charged with corruption and fraud, that the Commission’s building would be closed down!

Nevertheless, what we’ve witnessed thus far is a one-sided response to the spread of corruption. Moreover, fresh concerns have been raised regarding officials brought on board by the Interim Government, with the now-infamous ‘bond case’ of the Central Bank being a case in point.

This makes one wonder if any pre-emptive screening techniques were adopted by the new Administration, to ensure that such a situation wouldn’t arise.

And what of the allegedly massive corruption surrounding large-scale infrastructure development projects?

Apart from the many patently ad hoc deliberations on the temporarily suspended Colombo Port City project, we are yet to see conclusive evidence of how the talons of corruption were entrenched into the construction of highways, airports, sporting venues, etc.

This is not to say that bringing the issue of corruption to the fore is not appreciated. Indeed, what both the people of the country and valued foreign stakeholders look for is a climate of transparency, consistency and stability.

SINGAPOREAN MODEL One need only look at the First World nation of Singapore, to realise the benefits that accrue from adhering to a clean, clear and concentrated mandate for growth. That nation was able to transform itself into an economic powerhouse – despite the scarcity of natural resources – through a firm, corruption-free environment, enabling it to stand tall in the global landscape. All this, a mere half a century since the city state gained formal independence.

While the limited democracy of Singapore may not be the ideal model of governance in the eyes of many, Sri Lanka can certainly learn from the Asian Tiger’s success in cleaning up the system, to reap as many or even more economic rewards in the years to come.

Sri Lanka can and must make a concerted effort to deal with, and resolve, a legacy of corruption, nepotism and selective law enforcement… if it is to ever be seriously considered a developed nation in the 21st century.

One need only look at the First World nation of Singapore, to realise the benefits that accrue from adhering to a clean, clear and concentrated mandate for growth…

WHITE-COLLAR CRIME

C. Weliamuna provides an update on Sri Lanka’s anti-corruption drive

Compiled by Anya Weerasinghe

The election victory of presidential candidate Maithripala Sirisena resulted from a battle that was fought on the promise of good governance and an end to the culture of corruption that the island has been submerged in for too long.

These pledges were not mere campaign tactics; but rather, a response to the collective needs voiced by millions of voters who desired change. People started exercising their freedom of speech, and mainstream print and electronic media opened the floodgates of allegations that have accused high-ranking individuals and political figures of ‘grand corruption,’ on a scale which the island hadn’t witnessed before.

Following Sirisena’s victory, the Interim Government established the Anti-Corruption Committee, headed by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe. With some 2,000 charges of bribery and corruption, the committee has its work cut out.

J. C. Weliamuna, a member of the committee, has this to say: “There has been a huge discrepancy in the name of development and inquiries, and one would think that it is a five to 10 percent gap. But the sad reality is that it reaches 30-35 percent, some even up to 400 percent. Though it will take time to look into each of these allegations, we will not stop at looking into past occurrences. Present cases will be thoroughly investigated as well.”

CONTRASTING CRIMES However, white-collar crime is in stark contrast to traditional crimes, in terms of the profile of perpetrators, nature of the actus reus or criminal act, losses suffered by victims and, of course, the astronomical social cost. In fact, we’re told that it’s one of the most common crimes in this country.

It is generally known that white-collar crimes are committed by professionals. They are viewed as a deviation of the violator’s occupational role. According to analyses and reports, one of the main causes of the global economic downturn of not long ago was the large number of white-collar crimes that were rarely apprehended by criminal justice systems across the globe.

So where do we, as a nation, stand?

In Sri Lanka, several probes into large-scale financial misappropriation are being conducted, but the question remains as to how soon these investigations will be completed. Examples and allegations abound. The alleged US$ 122 million misappropriation during the construction of the Kerawalapitiya power plant is a case in point. Then, there’s the 400 million rupees expended on a team of international advisors, as well as the oil hedging deal that reportedly produced a loss of Rs. 7 billion.

A sum of 14.5 million dollars has apparently been misappropriated in purchasing four MiG aircraft for the Sri Lanka Air Force, from Ukraine. Fingers have also been pointed in the direction of the Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port, in Hambantota, which cost US$ 307 million and will need an additional one billion dollars to complete. The Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, which incurred an operational loss of Rs. 2.75 billion last year, is also under the investigative radar.

There are more allegations, with many more to follow, one feels. They include expenditure to construct hundreds of houses, provide medical assistance to the north, install electricity schemes in rural villages and grant enhanced educational facilities to countless schools.

ANSWERING TAXPAYERS The question is whether these initiatives, which absorbed billions of rupees from public funds, are credible and above board. And while the cost of living continues to spiral upwards, is it viable to dip into Treasury coffers to fund such investigations?

Taxpayers want answers…

True, people have the right to know why and where public funds are being expended, much like they have the right to expect the offenders to be brought to justice.

However, prosecution and conviction of white-collar crimes have proven to be a Herculean task, because the provisions in the Penal Code or criminal legislation are extremely technical and particularly difficult to prove.

As Weliamuna points out, white-collar crime investigations are exceptional, as they require a significant amount of time and because leads are often entrapped in legal technicalities – thanks to the complexities of legal provisions.

The criminal justice system, therefore, needs to invest in training and educating investigators, lawyers and judges.

And for this, the national budget must lead the way and walk the talk, by allocating substantial sums to promote the fight against corruption.

ZERO TOLERANCE At the end of the day, it boils down to each and every individual’s willingness to be the change they want to see – meaning, refuse to give or take, in the context of bribery and corruption.

But many are viewing this as the perfect opportunity for the new heads of state enterprises, the political fraternity and businesspeople to prove that ‘Yahapalanaya’ (good governance) comes with the promise of zero tolerance for bribery and corruption – including white-collar crime.

TALKING POINT

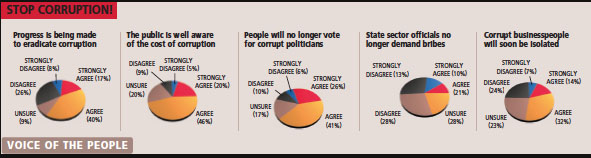

EXCLUSIVE NATIONWIDE OPINION POLL | CONDUCTED BY TNS LANKA | COMMISSIONED BY LMD

SAYING ‘NO’ TO CORRUPTION

Citizens detect a need for a better focus in wiping out corrupt practices

This comes as little surprise, given that Sri Lanka’s new rulers came into power on a platform of zero tolerance for infractions of the law.With everyone and everything, from supporters of the former regime to state corporations and their previous heads, hogging the media spotlight for alleged wrongdoings in the more recent past, purported acts of bribery and corruption have become a major topic of conversation in local circles.

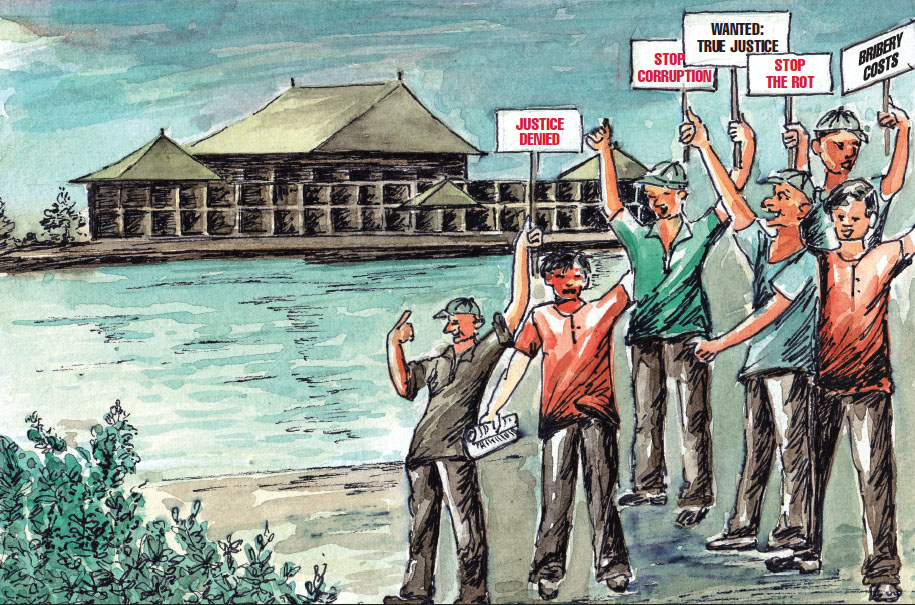

In a bid to check the pulse of the people, TNS Lanka’s exclusive nationwide poll for LMD reveals that 57 percent of the people do believe that progress is being made to stamp out corruption. However, at least a third (34%) of those polled state that not enough is being done to stem the tide, with some claiming that acts of corruption continue to take place while policymakers simply pay lip service to the spreading cancer.

Two-thirds of respondents agree that the general public is aware of the cost of corruption, with the media appearing to play a key role in this regard. But 14 percent of those consulted ‘disagree’ on the premise of public awareness, noting that the people are not privy to all the cost details pertaining to a given case of corruption.

Meanwhile, a sizable 20 percent remains ‘unsure’ about the level of public awareness on the monetary value of corruption.

On a more positive note, according to 67 percent of the survey sample, the citizens of Sri Lanka will no longer elect corrupt politicians into power, primarily as a result of the democratic framework that is in place. Nevertheless, the fact that a third of the people are not confident of this being the case is a cause for concern.

Equally troubling is the claim that state sector officials continue to demand bribes, as revealed by four-in-10 of poll respondents, with some going so far as to rather ominously declare that such instances of bribery ‘can’t be stopped.’ A case in point, as highlighted by a segment of respondents, pertains to bribes requested when parents attempt to admit their offspring into public schools, which effectively dilutes the very concept of free education.

As for the corporate sector, a near majority (46%) of the people are of the view that corrupt businesspeople will soon be isolated, asserting that this outcome simply ‘must happen’ (although rather perplexingly, stating that ‘it is temporary’).

The 31 percent of respondents who hold an entirely opposing view note that it will be business as usual even with instances of corruption, and – perhaps rationally – that ‘for money, anything can be swept under the carpet!’

In the eyes of the people, any hope of a corruption-free Sri Lanka will entail citizens calling for those who engage in corruption to be dealt with by the law, and that they inform the law enforcement authorities when incidents of bribery and corruption take place – all the while ensuring that they, themselves, do not engage in any form of corruption whatsoever.

Respondents also urge their fellow Sri Lankans to elect the right people into power, and get together to intercept those who break the law, amidst the appointment of official commissions to probe the corrupt practices that have allegedly spread their roots far and wide in the country.

METHODOLOGY Based on a random sample and face-to-face interviews with 400 respondents between 18 and 55 years of age, with an equal gender divide. The sample covers Colombo and the outstations in equal proportions.

ONLY A SOCIETY FREE FROM FEAR CAN TACKLE CORRUPTION

BY Dr. Jehan Perera

Public criticism of the Interim Government has been growing, even from amongst those who supported the new regime, following the election that brought it to power. One of the major issues at the presidential election was that of corruption and abuse of power. During the election campaign, there were photographs of allegedly ill-gotten properties, some of them being wheeled onto aircraft.

Allegations of infrastructure costs that had been inflated several times over were rife, too. And cases of political and even criminal killings were laid on the doorstep of the former government.

SLOW PROGRESS Since the election of President Maithripala Sirisena, revelations and allegations of corruption during the term of the previous government have mounted. There is concern that the new Government is proceeding too slowly on matters of past abuse of power and corruption. This is seen as a sign of weakness on the part of the Government; or even worse, as an indication that members of the new regime have been bought over by corruption themselves.

The bland denials of corruption by those accused also cause confusion among the general public, who are beginning to wonder whether allegations of corruption are true.

The Interim Government has pledged to establish effective systems to deal with the rot of corruption. Key to this endeavour would be to set up an independent public service, police and judiciary. They would underpin the workings of other institutions such as the Bribery Commission, to take those who are accused of corruption to task.

This new system will become a reality, along with the passage of the 19th Amendment. Those who head the institutions that must take action against corruption were appointed by the previous Administration, so their loyalties could well be divided.

INSIDER TRADING The issue of insider trading in the sale of government bonds has also damaged the new Administration’s credibility. The media has given widespread coverage and a detailed account of alleged irregularities regarding the bond auction. But the investigation panel appointed by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has been viewed with scepticism, as it is represented by members of his party.

However, Wickremesinghe provided a strong defence of his actions as being a major improvement on the pattern that had existed.

The argument, backed by examples, is that the very fact that an investigation is being carried out – and the person responsible being on leave, for its duration – is a laudable departure from the practices that existed in the past.

RENEWED OUTLOOK This is in contrast with the way in which issues of corruption and abuse of power were dealt with under the former government. It did not take any action against those within its ranks who were accused of corruption. During the 10-year term of the former government, and especially in its latter phase, corruption scandals were hinted and whispered about.

But there was no public outcry. According to those who are in the know, the lack of a public outcry was because critics of the then government were fearful of their safety. So officials and ministers continued doing what they did, because there was impunity. This situation has changed since the presidential election. The fear to speak out and protest against corruption, even at the highest levels, has seemingly disappeared.

Although the incumbent regime was unable to implement all the promises made in its 100-day programme, it succeeded in changing the threat perception in society. This is to its credit. The thrall of fear that silenced the public outcry against corruption and abuse of power no longer exists.

People are no longer in fear of government and white vans that abduct opponents. The protection of human rights needs to be institutionalised. This will happen, when the public service and judiciary become independent of political interference, as envisaged by the 19th Amendment.

TIME WILL TELL The freedom to live without fear, to meet without restrictions and to speak without being subject to retaliation are the most basic of human rights – and the foundations of good governance. If these foundational rights exist in society, good governance is bound to come sooner rather than later.

There will not be a need to give whistleblowers immunity to make complaints. People are already making complaints. The criticism of the new Government – for permitting corruption and abuse of power within itself, so early in its term – is a sign that civil society has been empowered.

Corruption and abuse of power is deep-rooted in society and in governmental structures. It will take time to root out.

UTTERLY BROKEN

BY Saro Thiruppathy

Over time, many people have defined corruption. But the definition I find most appropriate is Leslie Palmier’s – the use of public office for private advantage. As an adjective, the word ‘corrupt’ means utterly broken, and the term was said to have been first used by Aristotle. To which Cicero added the terms ‘bribe’ and ‘abandonment of good habits.’

SHAPES AND FORMS Corruption takes many shapes and forms. It ranges from petty to grand corruption. In developing countries, it is one of the most destructive factors, both socially and economically, as it exacerbates poverty, retards development and drains the economy, while creating a mountain of debt for generations to bear.

Petty corruption is generally seen in developing countries, where public servants are underpaid and are prone to delivering state service for a small consideration; or perhaps, overlooking a misdemeanour for a favour or a greased palm. In a worst case scenario, the consideration could even be sexual.

But grand scale corruption which occurs at the highest levels of government often subverts the political, economic and legal systems, in its effort to secure large financial and other benefits. This form of corruption is possible in countries where the separation of powers between the executive, legislature and judiciary is elastic, allowing for the Rule of Law to fall between the cracks. Grand scale corruption is often systemic, as a result.

Politicians are beholden to their supporters. They’re often called upon to honour promises made during the hustings. And these pledges are often fulfilled by corrupt means. In neopatrimonial regimes, where state resources are used by the ruling elite to secure the loyalty of their political followers, the state becomes an extension of the ruler’s domain – and bribes and other illegal tender become the norm. Like many developing democratic countries which have suffered autocratic regimes, Sri Lanka also has its fair share of corrupt practices and practitioners.

INSIDIOUS PROCESS Corruption is an insidious process, and it often infiltrates all sectors. But it is mostly found in public services, and evidenced through political, judicial and police corruption.

So what’s the big deal, if someone wants a little something to perform his or her duty, or not – if that’s what is required? Does it really impact on the country as a whole, if a policeman who is going off duty needs 500 bucks to buy milk and eggs for his kids, and seeks a bribe from an offending motorist, in order to spare him a traffic ticket?

Every act of bribery and corruption, like those tiny drops of water making a mighty ocean, contribute to the spread of the cancer, with a determination to break down the social fabric of a country and the Rule of Law.

As Carl Friedrich notes, corruption is deviant behaviour associated with a particular motivation – namely, that of private gain, at public expense.

WEARY WATCHDOGS In countries where protracted internal conflicts have zapped the nation, society’s watchdogs are also often weary. Wars provide a plethora of opportunities for the accumulation of wealth, and corruption pervades many aspects of state operations ranging from procurement kickbacks, to ‘the best price’ for tenders.

While the public service is thus engaged in feathering its own nest, governance is generally relegated to the back burner, from the lowest to the highest in the land.

People-centred priorities are shaky or absent, and this is clearly demonstrated by the state of Sri Lanka’s health care and education sectors. When personal gain overrides good governance, then governments and their lackeys start dabbling in dubious development projects and schemes, which can be easily ‘sold’ to a war-weary populace, so that officials can rake in the filthy lucre by truck or planeloads.

Furthermore, as society’s morals decay, the dark underbelly of the criminal world (such as human and drug trafficking, and money laundering) begin to surface, as the environment is conducive for such activities to thrive.

Robert Klitgaard, in his book Controlling Corruption, notes that corruption will occur if the corrupt gain is greater than the penalty, multiplied by the likelihood of being caught and prosecuted: Corrupt gain > Penalty x Likelihood of being caught and prosecuted.

Later, Constantin Stephan amended this formula slightly: Degree of corruption = Monopoly + Discretion – Transparency – Morality.

CONSTRUCTION OR CORRUPTION?

BY Anya Weerasinghe

Recently, a T-shirt worn by a man riding his bicycle caught my eye. It read: ‘I must change, for my country to change.’ Isn’t that food for thought, Sri Lanka? After years of drowning in an ocean of ‘nepotism,’ as some call it, voters across the nation voted for change.

Amal Kumarage (a Senior Professor at the Department of Transport & Logistics Management, University of Moratuwa) labels the scenario as “attempted highway robbery.” He sheds light on how political leaders and reputed contractors have planned to “wilfully” forego standard procedures and inflate the cost of highway projects.

He applauds the people of Sri Lanka, for speaking up and demanding a change, which “prevented the country from spending Rs. 504 billion, for what should have cost 217 billion rupees on the Northern Expressway project alone.”

NATIONAL ROBBERY In a report published in a Sunday newspaper, Kumarage notes how the 197-kilometre expressway project, which was to be the “crown jewel” in the robbery, was really an act of corruption that was prevented merely due to the buzz of an election. The attempted ‘national robbery’ was channelled through negotiations with international highway engineering consultants evading vital procedures, he maintains.

Originally estimated at Rs. 35.7 billion, the projected cost of the 42-kilometre section of the proposed four-lane expressway from Mirigama to Mudalpolla reportedly reached a staggering 98.4 billion rupees. The feasibility report for this mega project was accepted by the Road Development Authority’s Planning Division, we’re told, although Kumarage points out that “these feasibility reports are yet to be made public.”

And there’s more! Studies reveal that benefits have been overestimated by about 150 percent, and Kumarage adds that “this casts serious doubts about the accuracy of the calculations.” The feeling out there is that there’s an obvious reason for these feasibility reports not to have been made public; but fortunately, the project has been suspended.

CURBING CORRUPTION But that does not mean that the people are satisfied. They want the alleged perpetrators to be identified. They need to know that retributive action will be taken against them. And they want to know whether the new Government will allow this sort of secrecy and underlying corruption to continue. How does the new regime plan on curbing such corruption?

Kumarage suggests a number of feasible methods through which the Government can tighten its grip on development projects like the extension of the Southern Expressway. Tighter procedures for project approvals; more government agencies to conduct annual financial, technical and management audits; and of course, a transformation of legislation to ensure that the majority of the board members of state institutions are not appointed by one minister, but by many different hands.

GREED AND PILFERAGE He explores ways in which our national highway development should be pursued, without the hands of greed and pilferage. Urging the country to fight against such corrupt practices, Kumarage stresses the need to “clear the stables of the many players that aided and abetted this attempted national plunder, so that the restored highway programmes can be protected and made productive.”

And he asserts: “It would be the collective responsibility not only of the Government, but of civil society, professional bodies and even international financial institutions that have stepped forward to finance these highways, to ensure that good governance is applied to these highway projects – by ensuring that costs are minimised and the benefits maximised, by restoring and adhering to time tested technical, administrative and procurement procedures that have been wilfully dismantled in recent years. Failure to do that would only ensure a return to highway robbery, at some point in the future.”

The Government has a duty to oversee all infrastructure developments. Good governance interventions will surely bring about change.

DILIGENCE FACTOR Planning strategies must be made more efficient, and the Government plays the vital role of reviewing and examining past and future feasibility reports. Relevant RDA divisions and engineers should review and approve structural designs. And government agencies that handle these projects, on behalf of the public, need to “be diligent in exercising their professional judgement to safeguard expenditure,” says Kumarage.

At the end of the day, it boils down to each and every individual’s willingness to stay away from corrupt habits, and to be the change they want to see.

Kumarage concludes by reminding us that “we could have built all our highways for the price of one!”

So come on, Sri Lanka! Isn’t it about time we fought against corruption disguised as construction?