Cities Worldwide Are Reimagining Their Relationship With Cars

At a time when most of humanity lives in cities, where do cars belong — especially the old, polluting ones that make city air foul for people to breathe?

That question has vexed city officials across the world. Many are trying a variety of measures to reimagine the role of automobiles, the machines that forever changed how people move.

The immediate motivation is clear: City dwellers want cleaner, healthier air and less traffic. The long-term payoffs can be big: Curbing transportation emissions, which account for nearly a fourth of all greenhouse gases, is vital to staving off climate catastrophes.

And so, cities, which account for a large majority of global emissions, are dangling both carrots and sticks to persuade their residents to get out of their cars — or into cleaner ones.

Several have begun by making it expensive to bring older diesel cars and trucks into the city center. Some are aiming to keep out diesel vehicles altogether during rush hour (Bristol, by 2021, for example) and eventually all vehicles with internal combustion engines (Amsterdam, by 2030). Several offer incentives to switch out conventional cars for electric ones.

Some mayors have come under intense political pressure to address the health hazards of air pollution. “They see the growing concerns about the health effects of air pollution,” said Jane Burston, head of the Clean Air Fund, a London-based charity.

There are road bumps though.

Delhi, choking on toxic air, is struggling to staunch the flow of new cars and motorcycles on the roads, while in Madrid, where tens of thousands of delegates are to gather next month for international climate negotiations, the effort to restrict cars has turned into a political battle.

In London, Tightening Limits on Pollution

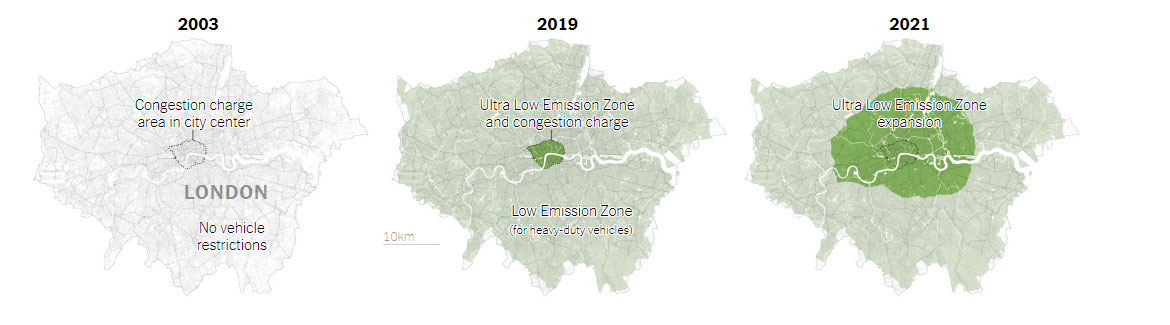

London’s effort to reimagine the role of cars began early. In 2003, the city started a congestion charge of 5 pounds, about $8 at the time, to drive a car or truck into the city center on weekdays between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. The charge has since risen to £11.50. (New York City, packed with cars and noisy, diesel-burning trucks in its city center on weekdays, will be the first American city to adopt a congestion price, but not until 2021.)

In April of this year came a new Ultra Low Emissions Zone levy on top of the congestion charge. It applies around the clock to the worst-polluting vehicles: older-model gas and diesel cars, trucks and motorcycles. Altogether, driving a car into central London can now cost up to £24 on weekdays.

By October 2019, nitrogen dioxide levels in the air had declined by 36 percent compared to February 2017, according to an assessment by the city. There were nearly 13,500 fewer of the most polluting vehicles in the city center on an average day, compared to the month before the new rules came into effect.

London has taken other measures to clean up its air. No new licenses are offered to black cabs that run on diesel. The city offers a roughly £3500 incentive to small business owners and charities to trade older polluting cars and vans for electric ones.

These programs were spurred in large part by concerns for public health: Exposure to the city’s polluted air resulted in more than 9,000 premature deaths in 2010, according to official figures.

In Beijing, a License Plate Lottery

The Chinese capital is a portrait of what cars can do to a city — and also what a city can do to its cars. The number of vehicles in Beijing nearly tripled to 5 million in 2011 from fewer than 2 million in 2000. Beijing became notorious for its bad air.

The city turned to some familiar measures: financial incentives to scrap older diesel-burning cars, congestion zones, stricter tailpipe emissions standards.

In 2011, began an unusual strategy. Officials instituted a lottery to issue new car license plates, essentially forcing car buyers to wait until they can actually take a new car out for a spin. There are more lottery slots for electric vehicles than for conventional ones, so the wait is longer for would-be buyers of the latest gas-powered S.U.V. Not least, every gas-powered vehicle must remain idle one day each week, as determined by the last digits of its license plate.

Those restrictions have inspired subversion. The wealthiest have bought more cars, sometimes registering them outside the capital, so the city has in turn has imposed new restrictions on how often out-of-town cars can park in the city.

Beijing’s air has improved, at least in part because of these restrictions. A United Nations report, relying on government data, found that between 1998 and 2018 levels of transportation-related pollution decreased markedly (nitrogen dioxide declined by 55 percent and the fine, lethal particulate matter known as PM 2.5 by 81 percent). But, the city’s air quality still fails to meet national standards for fine particulate pollution and far exceeds levels the World Health Organization deems safe to breathe.

In New Delhi, Little Progress and a Growing Crisis

New Delhi’s air quality is today as notorious as Beijing once was. It is among the most polluted cities in the world because of a year-round combination of vehicle, industrial and construction-related emissions, as well as seasonal crop burning.

Delhi has taken several steps to reduce tailpipe pollution: a vast Metro system, a peripheral highway designed to keep cargo trucks out of the city, restrictions on older and more polluting vehicles, and a requirement for all buses and taxis to switch from diesel to less-polluting natural gas.

That has made barely a dent against the new motorcycles, cars and trucks coming onto the roads. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of new cars registered in the capital grew by 11 percent to a total of nearly 9 million, according to an analysis of government data by the Center for Science and Environment. The report’s authors found that 49 percent of the miles traveled every day in the Indian capital are by bus and metro, while 51 percent are by private vehicles. “There is a real need to expand public transportation in the city,” said Anumita Roy Chowdhury, the center’s director of research and advocacy.

In November, when the city was blanketed by hazardous air, Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, campaigning for re-election, rolled out the third and strictest measure to curb the number of cars on the roads. License plates ending in even and odd numbers would have to take turns every other day for the first two weeks of November, which is peak pollution season. Mr. Kejriwal, facing a bitter re-election contest, extended the ban for the first time to vehicles used by federal government officials.

Will it work? The last two times an odd-even measure was tried, it improved the air a bit, according to a study by the University of Chicago. But it was a temporary gain, and the city’s air remains extremely hazardous for the approximately 20 million people who live there.

In Madrid, a Partisan Tug-of-War

The Spanish capital is in the throes of a heated debate about what kind of a city it wants to be, and cars are at the heart of it.

City officials last year rolled out one of the toughest auto restrictions in the world: A ban on most conventional cars in a portion of the city center, with fines for violators. The measure came after the European Commission said Madrid was falling short of its air-pollution reduction targets. After the ban, according to the city’s own air pollution sensors, there was measurable improvement.

Not everyone saw it as an improvement, though. Conservatives won a city election this year and they were keen to undo their liberal predecessors’ decrees. In July, the city announced it would scrap the fines, marshaling its own data showing that pollution had worsened around the no-car zone.

The reversal was short lived. Within a week, a judge stepped in, ordering the city to continue imposing fines for those who drive into the city center. The judge’s rationale: People need to breathe clean air.