CHINA IN AFRICA

DEBT TRAP DIPLOMACY?

Saro Thiruppathy assesses the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on impoverished nations

A ‘string of pearls’ was how the US referred to China’s geopolitical ambitions in the Indian Ocean back in 2005 – an exotic reference to Chinese plans to reestablish its ancient Silk Road. Two thousand years before then, China’s imperial envoy Zhang Qian helped establish the Silk Road, which comprised a network of trade routes that linked the Asian mainland to Central Asia and Arabia.

The reference to silk was because it was China’s most important export at the time and the Silk Road contributed to the development of the entire region for centuries.

MODERN SILK ROAD Two millennia later, China’s President Xi Jinping began the arduous process of establishing a modern version of the ancient Silk Road. This network would consist of railways, roads, utility grids and pipelines, which would link Central, West and parts of South Asia with China. This uber ambitious plan was known as the One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR).

By 2015, Xi’s plan was approved by China’s State Council and the OBOR (comprising the Silk Road Economic Belt as well as the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road) was intended to link regional waterways at an expected cost of US$ 1 trillion.

This network of overland corridors and shipping lanes is now known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), stretching from Southeast Asia all the way to Eastern Europe and Africa. It includes 71 countries (of which nine are in Africa), half the global population and a quarter of the world’s GDP. Twenty more African nations are currently discussing BRI cooperation.

HARD TO PORT Sri Lanka has been the recipient of massive loans from China, many at commercial interest rates. But the country has been left with a burgeoning debt portfolio and little or no income from unproductive projects funded with China’s money. Eventually, the Sri Lankan government leased its port in Hambantota and the Port City (CIFC), which is being constructed on reclaimed land in Colombo to the Chinese for 99 years to help manage its debt crisis.

The government of Tajikistan handed over disputed land stretching more than 1,000 square kilometres to China in lieu of debts being written off. Analysts speculate that the Wakhan corridor – which sits between Tajikistan, China’s Xinjiang province and Pakistani occupied Kashmir – is of geostrategic importance to the Chinese.

In August, Malaysia cancelled BRI projects worth US$ 22 billion because the newly elected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is concerned about the spectre of rising debt and the risk of neocolonialism.

In 2016, China accounted for 82 percent of Djibouti’s external debt and there’s speculation that the latter will hand over its Doraleh Container Terminal to the Chinese in lieu of monies owed.

ENERGY POWER China has enjoyed a long and friendly relationship with Africa, and now needs its support if the BRI is to be a success.

In the space of a year (2016/17), Chinese loans to African energy and infrastructure projects rose from US$ 3 billion to 8.8 billion dollars. Nigeria and Kenya are the main beneficiaries, having received nearly 40 percent of the funds since 2014. Other African beneficiaries include Djibouti, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia.

The failing energy sector is a major obstacle to development, and China is filling this void with funds, labour and technology. Some examples of BRI largesse include the energy sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, which benefitted from a cash injection of US$ 17.5 billion. Oil and gas received 3.2 billion dollars, and transport enjoyed US$ 5.5 billion in investments.

China also provided about half of the funding for Nigeria’s Mambilla hydropower plant, Kenya’s Lamu coal-fired power plant, South Africa’s Medupi coal-fired power plant and Zambia’s Kafue Gorge lower hydropower plant.

THE FAST TRACK Under the BRI, the Chinese built Kenya’s 466 kilometre railway from Nairobi to Mombasa with plans to extend the network to South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. They also constructed a 750 kilometre electric railway from Addis Ababa to neighbouring Djibouti. And in exchange for major investments, preferential loans, a pipeline and two airports, Djibouti is the location of the first Chinese military base overseas.

Beijing is not limiting its interventions to East Africa; it is planning infrastructure projects from Angola to Nigeria with ports, to dot the coast from Dakar to Libreville and Lagos. China has also given the nod to supporting a pan-African high-speed rail network at the request of the African Union.

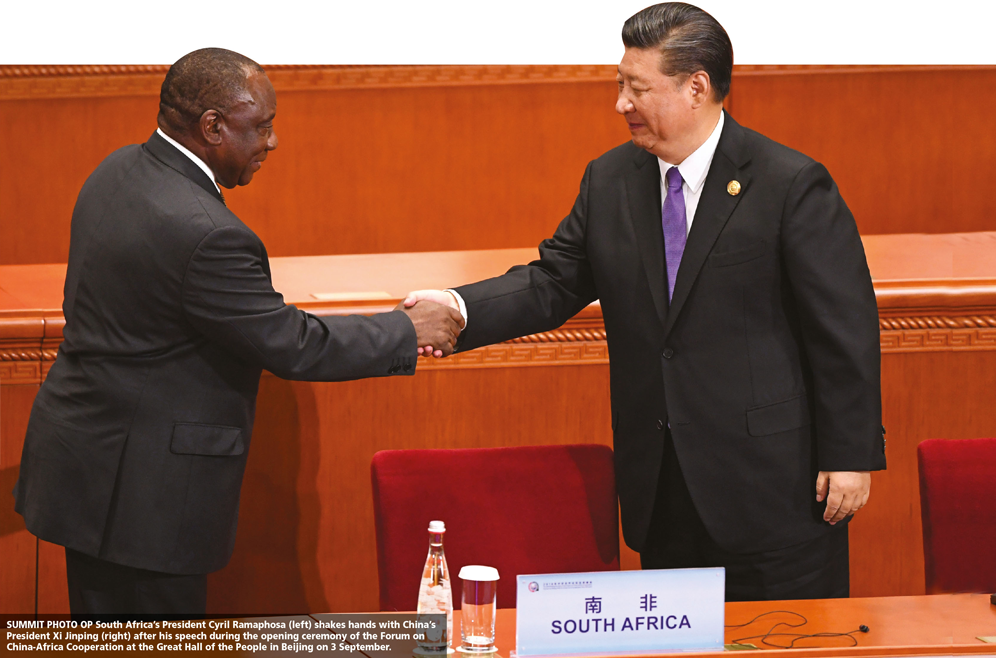

DEBT DISTRESS Borrowing is easy but the burden of spiralling debt experienced by BRI beneficiaries along the way is a cause for concern and Beijing used the China Africa Summit in September to allay the fears of stakeholder nations, as well as address what is being referred to as ‘debt trap diplomacy.’

But analysts wonder whether as in the case of Sri Lanka and Tajikistan, some of Africa’s enormous natural resources will eventually belong to China if African beneficiaries continue to remain in the red. Or could it be that since Africa’s strategic global position provides ample access for China to the Middle East and Europe, its location alone serves as a satisfactory payment for the massive investments of the Chinese on the continent?

Either way, it is yet to be seen whether the benefits will eventually be skewed in China’s favour alone or whether a win-win situation will emerge for Africa and others along the famous Silk Road.

Leave a comment