BREAKING NEW GROUND

LMD ARCHIVES (JANUARY 1996)

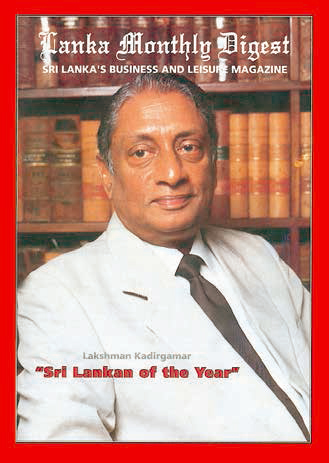

Lakshman Kadirgamar

LMD’s FIRST SRI LANKAN OF THE YEAR

That Prabhakaran and the LTTE are losing the goodwill and support of the world is not due to sheer luck, nor is it a chance achievement. Focussed, strategic thinking and intense behind the-scenes activity have parted the dark clouds of despondence, and the light has begun to shine through, albeit faintly.

Silently diligent, Sri Lanka’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Lakshman Kadirgamar has laboured hard to bring about the present favourable outlook for Sri Lanka. What makes the whole effort stand out is the single fact that Kadirgamar, while being Tamil, has thought and worked as a Sri Lankan. As he himself says: “I don’t represent Tamils.” In fact, he persists: “I don’t really represent anybody.” Indeed so, for he is a nominated member of parliament

and therefore, has no electorate.

He has no voters to please; and thus, can stand aside and be objective.

Talking to the Foreign Minister within the sanctuary of his library, surrounded by his legal tomes, it was easy to see that he is no run-of-the-mill politician. There is no doubt he speaks his mind. Worthy of mention is a purple patch from his speech to the UK-Sri Lanka Friendship Society, in 1993: “In England, members of parliament are not called honourable members but some of them are. In Sri Lanka, they are called honourable members but some aren’t.”

Distinguished, and with a dignified demeanour, salt-and pepper-hair, eloquent eyes mellowed with the years and a finesse acquired through years of exposure to global intellectual forces, Lakshman Kadirgamar is undeniably one of Sri Lanka’s success stories. Following a successful legal career, ending as President’s Counsel, and 14 eventful years at the UN, Kadirgamar says his foray into politics was very sudden – in fact, “a complete surprise.”

“I have had a very privileged existence,” he says. He has done things in his life which most others merely dream about. He feels it is time now to give something back to this country so dear to his heart: “I did not negotiate. I could have done some service even as a backbencher.”

Yet, that was not to be. Kadirgamar was given the portfolio of Foreign Affairs, which was right up his street. “I hit the road running,” he says. Part of his success and effectiveness is due to the fact that there was no learning period necessary. He already knew the ropes and was comfortable handling the tasks before him.

Kadirgamar says his priority, when he assumed office, was to improve Sri Lanka’s human rights record and dispel the climate of fear that shrouded the nation. Once this was accomplished, he knew it would not be long before the world changed its mind about Sri Lanka. A Commission of Inquiry was appointed to investigate cases of missing persons, and a bill was passed in parliament to enact a law against torture. Another bill was presented in parliament to set up a National Human Rights Commission. A Human Rights Task Force was appointed, and the security

forces were advised on human rights.

The minister had been pleasantly surprised by the resounding applause when he addressed the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in March 1995. He is the first foreign minister to address this forum. Generally, there is no occasion for applause at such gatherings with no public involvement. “I felt it [the applause] to be an indication that the international community was welcoming Sri Lanka back to the fold,” he says. Kadirgamar’s visits to other countries have been well thought out and systematically planned to achieve the best results. He considers Sri Lanka’s immediate neighbours to be a top priority.

His first visit as Foreign Minister was to Bangladesh, then China, which chaired the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). He is the first Sri Lankan foreign minister to have visited China since 1979. Next in line were India and Malaysia, with Pakistan coming later in July when times were convenient for the host and guest countries. During the minister’s visit to the US, he made sure he got Sri Lanka’s views across to as many people as possible. He met a number of Congressmen and held several press conferences in Washington D.C.

Kadirgamar considers Sri Lanka’s next tier of friends as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). He attended the Non-Aligned Foreign Ministers’ Conference in Indonesia; and in April, he made two very useful visits to Malaysia and Singapore with two large trade delegations. Then, it was to the West again, in particular to Germany – a major aid donor in the past, somewhat neglected in recent times – and then on to the UK.

As the minister notes, relations with India have had several ups and downs in contemporary times. “Yet, our ties with India can be so warm and cordial,” he adds. He feels Sri Lanka’s relationship with India is now at its best. It is not so much material help, as the understanding between the two nations, which is all important. This was very evident in India’s readiness to help douse the flames at the Kolonnawa oil installation when the Tigers set it on fire in October.

“I took a lot of trouble to explain to the world the true facts about the LTTE,” says Kadirgamar. The efforts have not been in vain, for the world is slowly yet surely beginning to realise that the LTTE is not an idealistic group of freedom fighters but a set of brutal and ruthless terrorists with no genuine desire for peace and a negotiated settlement to end the war.

Kadirgamar understands the importance of suitable diplomatic appointments in building a nation’s image. Within his first two months in office, the minister raised the percentage of career diplomats in the missions abroad from

30 percent to 60 percent. Even the non-diplomatic appointments were made with care, choosing high calibre, educated people. Kadirgamar makes special mention of Malaysia as a country Sri Lanka should try to emulate in

economic as well as political life. The two major communities in Malaysia live side by side in peace and understanding. There, the minorities were invited to share power with the majority – without the majority being forced to do so.

According to the minister, communication with Sri Lanka’s missions has been considerably improved with all of them now connected via the internet. The missions receive regular updates in the form of foreign ministry news bulletins. “It is quite modest,” he admits. Yet, such simple things had been overlooked before.

Kadirgamar hopes to create a new public information service from the foreign ministry in six or seven selected capitals of the world, in a move to counter LTTE propaganda. Kadirgamar feels there should be a non-partisan

approach to foreign policy and that on major issues Sri Lanka should speak with one voice. He also believes the present crisis needs to be handled with commitment and selflessness: “The issue of war and peace should not

be looked at from a selfish political angle.” He feels that one needs to be moderate at all times, understanding too but also firm when firmness is due, keeping the national interest paramount and sectarian interest diminished. “I

don’t espouse sectarian causes,” he remarks. He says he spent the best years of his life in a united Sri Lanka and sees no reason why thecountry should be divided now.

He seems cautiously optimistic about an end to the war and the prospects for peace in the future: “It all depends on Prabhakaran, who controls the LTTE and who is a totally unpredictable person. What is more, his previous

track record indicates he is not interested in peace.”

Yet, the minister hopes there might be a moderate element in the LTTE somewhere, which will respond to overtures for peace. But right now he feels the LTTE’s arrogance needs to be curbed, “and that, unfortunately, has to be done militarily,” he states.

The Tigers will then be rendered unable to dictate terms to the nation and could be dragged into the process of nation building like the other parties. “For that to happen, violence must end,” the minister adds.

He also believes it does not help when expatriate Tamils – even educated people – keep funding the Tigers. However, Kadirgamar feels that support from abroad has weakened substantially.

He believes all governments of the world understand that Sri Lanka was forced to take military action when faced with the threat of division of the country. But they hope that once the LTTE is weakened, the peace initiative

already on the table will be carried through.

In Kadirgamar’s opinion, when justice and fair play are required, they must be given. Also, the majority must make the minority feel welcome and comfortable. He believes the vast mass of ordinary people are decent human beings

who do not want war or hatred but merely to live in peace. He says leaders must always look for and encourage these natural instincts in people – and not fan the flames of passion for narrow political ends.

His vision is for a “just and durable peace.” It will come so long as selfish politics are not played, he believes. “We have had too much of it in the past,” he says. And this is when the national vision is distorted.

During the minister’s Oxford days, he was an opposing speaker in a debate on ‘Democracy is unsuitable for underdeveloped countries.’ Kadirgamar spoke with such eloquence and passion that his speech was likened, by the British press, to a “vintage champagne after a third-rate meal.”

He is still a champion of democracy – and above all, a Sri Lankan who has dissociated himself from the parochialism of contemporary society to serve his country with the strength of his convictions.