Boris Johnson’s battles

by John Pienaar

Boris Johnson is to be the UK’s new prime minister.

What drove him to the top?

“I’m not going to fight you,” Boris Johnson told me, after a moment’s silence. “You’re huge!”

I’d made my own preposterous suggestion on the phone to the then Conservative celebrity-MP for Henley in the autumn of 2002.

After a few minutes of cajoling and gentle persuasion he relented and changed his mind. “OK, I’ll fight you,” said Johnson. “But you’ll have to promise not to break my nose.” I did, of course. Promise, I mean. Not break his nose.

I had been recruited to take part in a televised bout of “celebrity boxing”, live on BBC Two.

In the end, the British Boxing Board of Control had more sense than I and, for a fleeting moment, Johnson had at the time. The boxing authorities judged that a high-profile fight between two barely trained middle-aged amateurs might be “reckless and irresponsible”. The “fight” was cancelled.

Johnson had pulled out by then, in any case. Not through any lack of “bottle”. Everything I have seen, heard or read about the UK’s new leader suggests no great fear of physical or, for that matter, political or social risk.

He clearly likes the idea of himself as a bit of a battler, not one to retreat from a scrap.

“Man or mouse?”, he is fond of saying before some sudden boyish challenge to a friend or colleague – a game of “whiff-whaff” [ping-pong] on the table in his office, or a quick competitive sprint.

In an interview with the Daily Mail recently, he gave his favourite quote as: “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.”

Nor did I detect then, or since, any conventional instinct to protect his dignity. Just the opposite. We had invited Johnson precisely because he cared so little for that. But he did, I think, feel it might seem a little ridiculous, even for him, to risk his profile in such a way before a live audience of millions, even for charity.

Incidentally, much later, as London Mayor, Johnson was said to have demonstrated his martial instincts by physically battling in a meeting room with David Cameron, like two overgrown schoolboys, for possession of a Treasury note setting out the available funds for transport in London.

Afterwards, as Andrew Gimson records in his biography of Johnson, both men claimed victory. We’ll never know the truth. It was, though, another glimpse into the deep rivalry underlying the outwardly friendly relationship between the pair.

At an uncertain and unstable time for British politics, for the economy and for the country’s place in the world, Conservative Party members have chosen a leader who defies almost every norm.

Any objective assessment of Johnson’s record, judgement and character throws up one perfectly legitimate doubt after another.

Yet his ability to connect with people (though not everyone and not all the time), to make them feel good about themselves and about him, is simply unique in public life. Whether at a feel-good time of national optimism, or, as now, a time of bitter division and much pessimism, it has turned out to be a gift which has helped carry him into Downing Street.

More than any of this, even though Boris Johnson’s depth of character may be little trusted by his critics and by quite a few of his supporters too, he made himself the leadership candidate most trusted by the deeply Eurosceptic Tory “selectorate” to deliver Brexit as promised and on time, on 31 October 2019.

At the time of writing, the most reliable verdict on that pledge is still: “We’ll see.”

So why Boris Johnson? And who exactly is he?

The young man

Boris is pretty impressive when success can be achieved by pure intelligence, unaccompanied by hard work

School report

The first thing to note is that he is not actually Boris at all, despite the rare distinction in politics of being known universally by that single name.

He was born Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson on 19 June 1964. He chose to be called Boris and his family, friends and eventually everyone else have amiably obliged him.

For one so stereotypically English, his ancestry is surprisingly varied – a mixture of English Christians, Turkish Muslims and Eastern European Jews. His maternal great-grandfather was an Orthodox Lithuanian rabbi. His paternal great-grandfather was a Turkish political activist, Ali Kemal, who was apparently lynched after falling foul of the nationalists then in power. Boris, Sonia Purnell records in her biography, was the name of a Russian emigre friend of the family.

Johnson was born in New York City, and spent his earliest days with father Stanley and mother Charlotte in a home opposite the famous Chelsea Hotel, hangout of many famous rock stars of the time.

His father began a master’s degree in agricultural economics, and after what he has reportedly hinted to be an unsuccessful attempt to recruit him as a spy (undergoing “the most intensive training in clandestine techniques known to man”) he worked briefly for the World Bank in Washington DC, before he was sacked.

Apparently, being perhaps something of a block off the old chip, he submitted a suggestion for a $100m loan to build three pyramids and a sphinx to help the Egyptian tourist effort. It was an April Fool joke. His employers were not amused.

Back in the UK, Stanley and Charlotte raised a family: a daughter, Rachel, who recently joined the Liberal Democrats before defecting to the then Independent Group as a candidate for the European Parliament (more successful as a journalist than as a politician); Leo who did well in finance, and Jo, who worked in Downing Street as a policy thinker under David Cameron, and became a respected minister under Cameron and Theresa May. The siblings were ferociously competitive. Stanley’s ambition was to raise a journalistic and political dynasty, and he did.

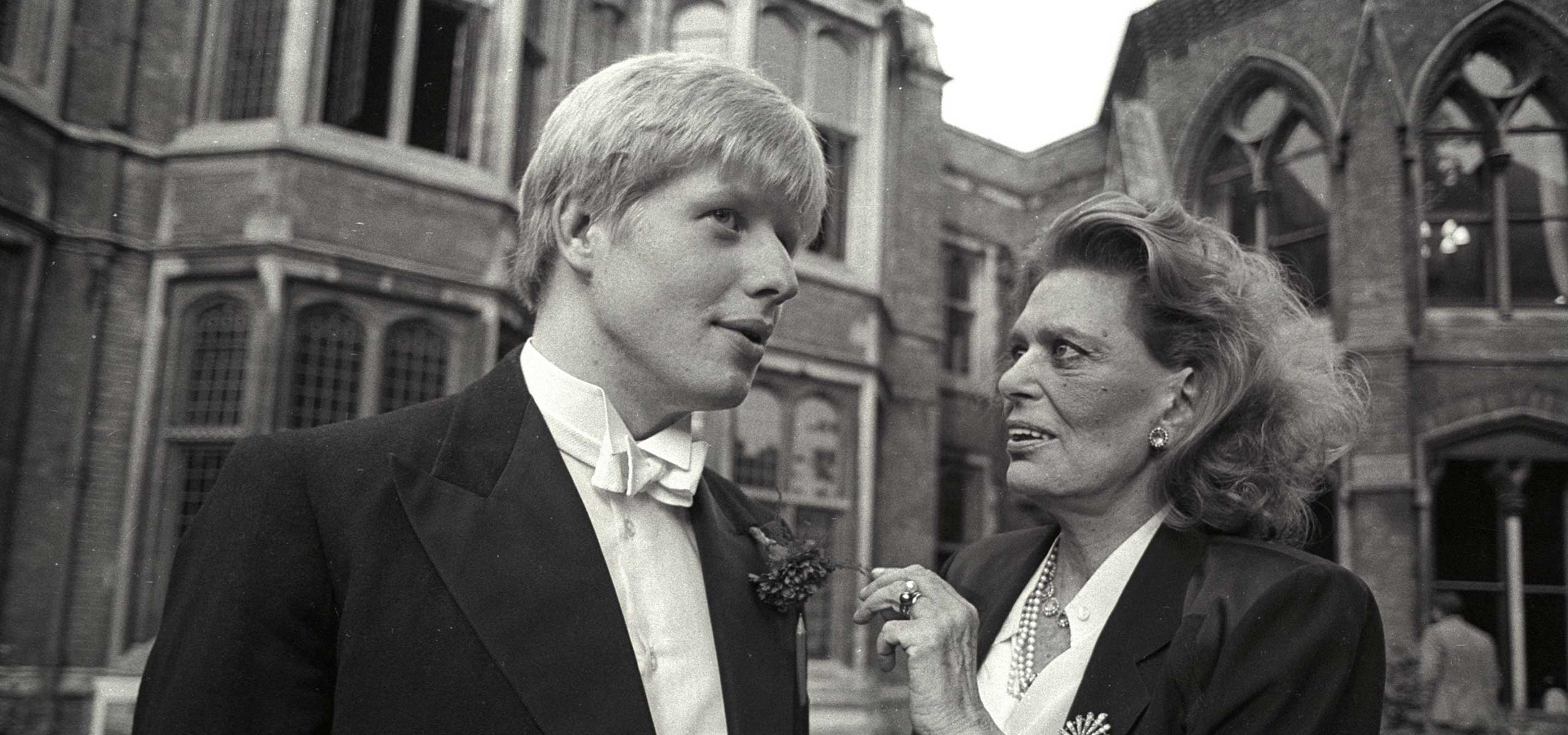

Young Boris was at Eton, and the family living in Brussels, when his parents split. He doesn’t like to speak of that time, or its effect on him, but it was painful. Charlotte – a celebrated artist – subsequently suffered a serious mental breakdown and spent nine months as a patient in a psychiatric hospital.

So Boris Johnson’s early life cannot be described as easy, or pain-free. His now famous amiable, bumbling persona – a close copy of his father’s – has sometimes been described as a defence mechanism, concealing a sharp brain and a fine but well-disguised instinct for personal advantage.

At any rate, after a spell at Ashdown House boarding school, Johnson went to Eton with an academically prestigious King’s Scholarship. He became a contemporary of, among others, David Cameron – and a close friend to then Viscount Althorp (now Earl Spencer), brother to Princess Diana, and Darius Guppy who was later to be jailed for five years for fraud.

At Eton, AB Johnson became “Boris” – rather posh, very English, somewhat eccentric and the deeply distinctive, deliberately dishevelled character we know now.

He was also very clever – “brilliant” according to one teacher – and endowed with what has arguably become a strong sense of entitlement to both make up and play by his own rules.

He was a formidable debater, and became adept at deflecting awkward questions with non-committal answers (as any journalist who has interviewed him can testify).

The report from his housemaster makes interesting reading now. He wrote of Boris to his father: “I think he honestly believes it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception – one who should be free of the network of obligations which binds everyone else. Boris is pretty impressive when success can be achieved by pure intelligence, unaccompanied by hard work.”

His character – clever, capable of achieving impressive results though always very much on his own terms – was forming. Future opponent Ken Livingstone wrote an attack on public schools while Johnson was a pupil.

He wrote a reply in the school newspaper, recounted in Purnell’s biography, dismissing his future adversary’s arguments as “twaddle, utter bunkum, balderdash, tommyrot, piffle and fiddlesticks”. His distinctive vocabulary seemed to be forming too.

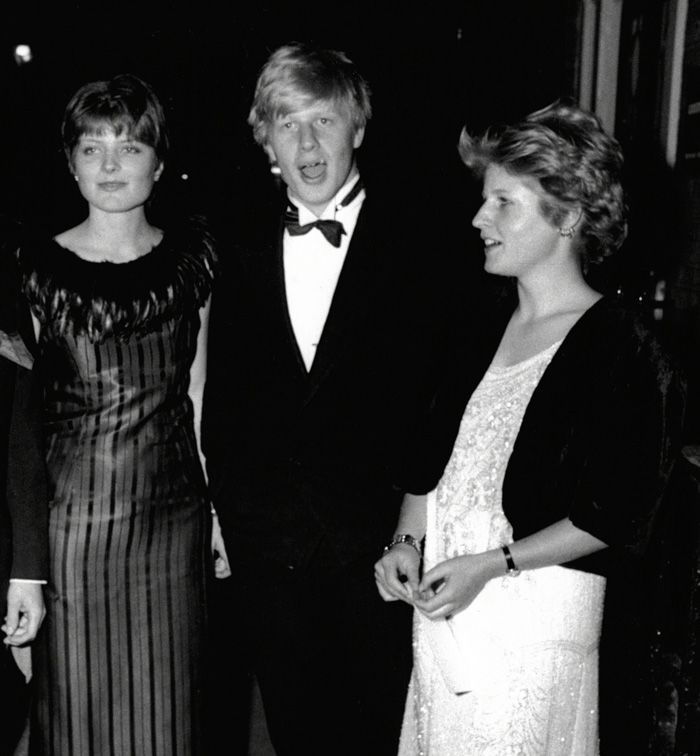

Johnson, like David Cameron and George Osborne – and also Jeremy Hunt – famously joined the infamous Bullingdon Club of rich, rowdy and elitist undergraduates.

Cameron has since played down this aspect of his Oxford career, with its trashing of dining rooms and debauchery.

Boris Johnson, it is suggested, has never been much attached to hell-raising, though the Etonian network was undeniably useful in pursuit of his great ambition of becoming president of the Oxford Union – historically, at least, a stepping stone to the office of prime minister.

Johnson met his first wife, Allegra Mostyn-Owen, at Oxford – another ambition. But he never attained the goal of a first-class degree in Classics, something friends say still rankles to this day. He did, though, make connections which became more than useful in what was to be a journalistic and political career of dizzying ups and crashing, if temporary, setbacks.

It has always proved hard to keep Boris Johnson down. In his run for the party leadership it was often said – by me among many others – that the only person capable of defeating Boris Johnson was Boris Johnson. From the earliest days of his career, he nonetheless seemed determined to try.

The journalist

Boris Johnson, the newly minted prime minister would, one imagines, hate being subject to the kind of reporting and analysis that Boris Johnson the fledgling journalist made his own particular trademark.

As a trainee fresh out of Balliol College, he joined the Times newspaper under the editorship of the near legendary Charlie Wilson – a tough, Glaswegian out of the old school of Fleet Street broadsheet journalism.

Johnson was found to have tried too hard to pep up a fairly innocuous story about the discovery of a palace of Edward II on the south bank of the Thames. His historical account was nonsensical, and an accompanying quote entirely made up.

He wrote how the king would frolic at the palace with his sidekick Piers Gaveston. Only Gaveston had been executed years before the palace was built, and the made-up quote was attributed to an Oxford academic who was also his godfather, but nonetheless, not surprisingly, complained. Johnson was sacked.

He’s got that quality that causes his believers to be prepared to overlook all the things people traditionally ask about. Is he truthful? Is he honest? Is he nice to his wife?

Sir Max Hastings

It might have been the end of his journalistic – and conceivably any other – career in any profession requiring trust. But it wasn’t.

Daily Telegraph editor Max Hastings, who had met Johnson while he was hosting the great and the good at the Oxford Union, gave him a chance to redeem himself and he grabbed it with both hands.

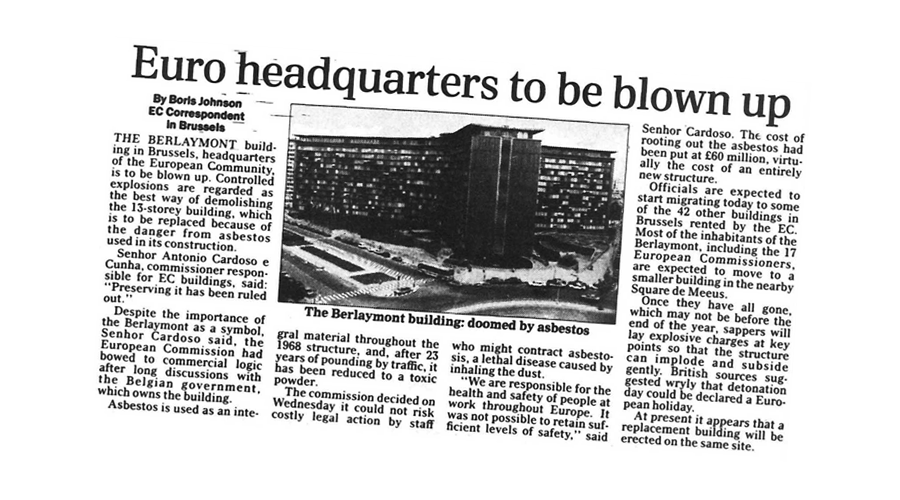

Soon, as the paper’s Europe correspondent in Brussels, Johnson made his name as a pioneer on what in 1989 became a new frontier of deeply Eurosceptic reporting.

Much of the reporting at the time was done by correspondents who were arguably much more sympathetic to the culture of what was then called the European Economic Community.

Johnson’s stories consistently made the front page, pleased readers who held the EEC’s “federalism” and interfering ways in contempt – some of them, like Iain Duncan Smith, now prominent political supporters of the new regime set for Downing Street – and made his work popular to the point of becoming cult reading.

His journalism artfully mixed fact with wild Eurosceptic fiction.

There were tales about unlawfully curved bananas, wrongly sized condoms, and one about the European Commission headquarters Berlaymont building being about to be blown up with dynamite because it was found to contain asbestos. Often, the reports made you laugh out loud, which only added to their force.

I remember running into him in Strasbourg, during a session of the European Parliament while I was a political reporter with the Independent. He was smirking at a name he’d invented for the leader of the Conservatives in the parliament, Sir Christopher Prout – “Brussels-Prout”.

He has a useful gift of somehow making you laugh even when his jokes are not especially good. But my former Independent colleagues, like other journos covering Europe, were not always so easily amused by their rival from the Telegraph.

“He was fundamentally intellectually dishonest, in my view,” David Usborne told Andrew Gimson in an interview for his book. “He was serving his masters in a very skilful way but I never felt he believed… He was a highly intelligent man, much cleverer than I was, he could see all these nuances and subtleties, but he wasn’t conveying them in his writing. It was a cheap thrill – a stunt, and quite a dangerous stunt really.”

As you’d expect, Max Hastings, his then editor, took a slightly indulgent view of his talented protege. He is perhaps rather less tolerant in retrospect. “I don’t think we ever caught him out in anything he deserved to be sacked for, or to be brought home from Brussels,” he told me in an interview for the BBC’s Panorama. “Boris’s relationship with integrity and truth, and with the right moral standards has always been a bit uncertain to put it politely.”

As we’ll see, not everyone has been inclined to “put it politely” when it comes to Johnson’s character and record. Max Hastings’ assessment of his former employee is striking.

“All human relations are about who makes you feel good… more than any other politician in British life today he’s a genius. He is absolutely terrific at telling people what they want to hear and he does it with wit, with elegance, with style.

“He’s got that quality that causes his believers to be prepared to overlook all the things people traditionally ask about. Is he truthful? Is he honest? Is he nice to his wife? None of that stuff matters.”

But Hastings has argued for some time that Johnson is unfit for national office, writing recently of his “moral bankruptcy, rooted in a contempt for truth”.

Some, including his biographer Sonia Purnell, have credited Boris Johnson’s Eurosceptic journalism in Brussels with creating the climate which nurtured anti-EEC feeling in the Tory Party and in doing so destroyed John Major’s administration.

That, I think, is a bit of a stretch. Major’s government was exhausted after 18 years of Tory government, and battle-weary after the struggle which ended Margaret Thatcher’s premiership in 1990. The Conservatives were tottering in the face of Tony Blair and New Labour’s assault and, vulnerable to the country’s appetite for “change”, were kicked out in the truly crushing general election defeat of 1997.

But as the Conservatives finally ran out of time, Boris Johnson was just getting started.

The celebrity

Johnson’s media career bore fruit, just as his efforts to cultivate his celebrity status blossomed, and his political efforts took root. He was a popular turn on the BBC’s Have I Got News For You, and he had quickly advanced to star columnist at the Telegraph, and editor of the Spectator soon afterwards.

After an unsuccessful run at the impregnable Welsh Labour stronghold of Clwyd South in 1997, his high media profile helped him pluck the plum candidacy of Henley.

He got into Parliament in 2001, succeeding Michael Heseltine, in his time a political super-heavyweight and aspirant premier himself, though obviously less successful in that ambition than Johnson.

For a while, it all seemed to be going almost too well. And it was.

Johnson – who was divorced in 1993 and later married the barrister Marina Wheeler – was given a shadow ministerial job by party leader Michael Howard. But he was sacked after lying about an affair with his Spectator colleague Petronella Wyatt.

In a recent interview with the BBC’s Today programme, Howard suggested sacking Johnson might have been a mistake. But that very recent moment of repentance came when Johnson was very much closer to the premiership he craved than Howard had ever been. Then, he was a mere junior arts spokesman. And it wasn’t Johnson’s only setback. Another had been, if anything, more humiliating.

A leading article appeared in the Spectator in October 2004 after the awful murder of Ken Bigley while a hostage in Iraq. It described the “mawkish sentimentality” of the reaction. Bigley was a Liverpudlian, from a city still raw from the deaths of 96 fans in the Hillsborough football stadium tragedy of 1989. For Howard, a passionate fan of Liverpool Football Club, it was too much, and he ordered Johnson to go to the city to apologise.

It became a grim media circus. Not the first to surround Boris Johnson. And not the last. He was constructing a reputation for gaffes and scrapes, but also having a way of somehow surviving them. That knack, as we have seen, has turned out to be very handy.

The tabloid flurry over his relationship with Petronella Wyatt wasn’t the only one of its kind. Newspapers have other tales on file. Yet, as Max Hastings told me, moral disapproval never seems to have stuck, or, where it has, to have inflicted permanent political harm.

Johnson himself often refused to answer interviewers’ questions about his private life during the Tory leadership campaign. They were not often asked.

Go back to his past writings, however, and he has argued for a liberal approach to the private lives of public figures. In a piece for the Telegraph in January 1998, defending the then US President Bill Clinton, he posed the question: “Does anyone think a bunch of uniformly virtuous politicians would make the slightest difference? Of course they wouldn’t… the press wilfully muddles the issue, feeding on public prurience and jealousy.”

Highs and lows have come and gone. None higher until now, perhaps, than his two spells as Conservative Mayor of London.

The then prime minister, his Eton and Oxford contemporary, David Cameron, was not at first keen on Johnson becoming candidate for City Hall. Would he be a liability? He was certainly a rival attraction.

Lord Coe was preferred, but didn’t want the job. Some believe Cameron’s lack of enthusiasm helped convince Johnson to go for it. And the prospect of the Tory Party scoring a huge victory in the capital, against the odds, became attractive in Downing Street.

Was his mayoralty a success? Depends who you ask. House building went up. Crime came down. “Boris Bikes” filled the streets. Critics say he inherited Ken Livingstone’s legacy, and that crime came down across the country.

In the build-up and aftermath of the 2012 London Olympics, it is reasonable to argue Johnson’s role as a frontman outweighed his actual contribution to delivering the event itself. His leadership rival, Jeremy Hunt, played a bigger role in the practicalities. Lord Coe did too.

But as a frontman Johnson had no equal. Obviously, he never intended to get stuck half way down a zip-wire near the Olympic site. For someone else, it might have been disastrous. For Johnson it was a comedic triumph. No wonder David Cameron – who always perceived Johnson’s unique potential – described him as a man capable of “defying gravity”.

Young and old, left and right, the crowds cheered, and that raises the question: “Who is the real Boris Johnson?”

Was it the leader of the metropolitan, multicultural, liberal and Labour-leaning capital? Or is it the darling of the Brexit-loving, deep dyed Conservative, and more socially conservative, party members who have elected him to be theirs and the country’s leader?

His critics – and some of his friends – believe the answer to that question is that Boris Johnson is whoever he needs to be to advance politically.

Another, slightly pseudo-psychoanalytical take is that he truly believes everything that he says or writes, at the moment that he says or writes it. That is barely a more flattering view.

Yet another view is that Johnson is at heart a “one-nation” Conservative, socially liberal and personally kind (a master at Eton says he never witnessed Johnson uttering an unkind word), and optimistic in a way that is infectious, and that this is the agenda he means to make the hallmark of his time in No 10. But will he? Can he?

MPs who were former colleagues at City Hall speak highly of his abilities. Kit Malthouse, who was deputy mayor for policing, said Johnson had succeeded in “tackling poverty, cutting crime – particularly knife crime, building the homes people need and delivering a cleaner, greener city”. James Cleverly, who also worked with Johnson as a London Assembly member, said: “I know he can run a successful executive operation because I was part of the team who did that in London for eight years.”

Both announced their intention to stand for the Conservative leadership before dropping out and backing Johnson.

There has been much talk of Johnson being a “chairman of the board”. The idea is that as prime minister he would surround himself with talented people – in much the same way he did as mayor – rather than trying to micromanage.

The contender

[Boris Johnson] will only succeed as prime minister if he broadens his focus and his appeal

Guto Harri, former adviser

The questions about Boris Johnson’s political judgement have been stacked higher by memories of his lead role in the campaign to leave the European Union, which won against all expectations, and later by two years as foreign secretary, his tenure distinguished chiefly by a succession of gaffes and diplomatic banana skins.

To be fair, he wrote his rude poem about the president of Turkey and a goat before he became foreign secretary. He had less excuse for obliquely comparing the EU to the ambitions to dominate the continent exemplified by Napoleon and Hitler.

His mistake in describing Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe – then already in custody in Iran – as teaching journalism in the country was more serious. He was simply wrong. The comments had “traumatic effects” for her, her husband later said, and were used to justify a second court case against her.

Westminster’s longest-serving MP, Ken Clarke, has filled all the most senior jobs in Conservative cabinets save that of prime minister. “[Boris Johnson] was a disaster,” he told me. “The diplomats were driven up the wall. He didn’t read the brief. The only thing he worked at were the photo opportunities at foreign meetings… quite the most hopelessly irresponsible foreign secretary I’ve ever known from any party.”

For an alternative, vastly more friendly view, you might try Camilla Tominey in the Telegraph. She hit back at all the “lazy caricatures”, and preferred to remember Johnson’s support as foreign secretary for girls’ education around the globe, as well as his backing for strong sanctions after the poison attack on the Russian defector Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, which resulted in the expulsion of 100 Russian diplomats by the UK and allies including the US.

She also drew attention to his habit of delegating tasks to trusted subordinates.

Now, Camilla Tominey is, of course, a colleague of Johnson’s on the Telegraph where he writes a regular and highly prized, highly paid column. Ken Clarke is a known critic of Brexit. My guess is you may already be predisposed to agree with one side or the other.

Either way, Boris Johnson was chosen to serve as foreign secretary not for his diplomatic skills, but because Theresa May wanted prominent Brexiteers in the cabinet jobs most closely tasked with delivering it. That plan didn’t work out particularly well for her.

Brexit ground to a standstill. Mrs May resigned, having failed wretchedly to achieve a mission which, in truth, seemed all but impossible from the moment of her disastrous “victory” in the 2017 general election, and Boris Johnson’s rise to replace her is now pencilled into political history. He’ll be hoping it makes easy reading in time to come. Again, we’ll see.

The story of Johnson’s role in the Leave campaign has been told too often to need much retelling here.

There were the two newspaper columns he wrote, one for leaving and one against. The friends (or former friends) like Roland Rudd, the financial PR man who now chairs the “People’s Vote” campaign, who told me bitterly how Johnson pledged his devotion to the Remain side shortly before announcing the opposite.

Sir Craig Oliver, then director of communications in Downing Street under David Cameron, testifies to a poetic text message from Johnson predicting Brexit would be crushed “like the toad beneath the harrow”, sent moments before he came out for the Leave side.

According to who’s telling the tale, it’s damning evidence that Johnson was never a true Brexiteer with some saying that he joined what he hoped would be the losing side (though still the one most useful to his leadership ambitions) or that he was genuinely torn by doubt until the last moment.

Does the accusation of dishonesty stick? Detractors point to the dubious slogan plastered on the side of the Leave campaign bus suggesting Brexit would free £350m a week for the NHS, and also the alarming suggestion that millions of Turks were waiting to enter the UK and swamp the health service almost overnight. The charge sheet of false or inflated campaign claims, with which Johnson became associated, is a long one.

Of course, Brexiteers are no less vocal in condemning the Remain side’s hair-raising economic prophecies – Project Fear. You will doubtless have your own view.

If Boris Johnson feels any regret – and I have never heard anything to suggest that he does – he has kept it to himself. A friend and close associate told me he is proud of what he achieved, and considers that he “owns” Brexit.

Another friend, his close adviser at City Hall, Guto Harri (a former BBC colleague) told me: “He has to focus very narrowly on the Conservative grassroots now. But he will know that he will only succeed as prime minister if he broadens his focus and his appeal once again way beyond that. It’s something he did pull off as mayor and I just hope he can do that again.”

Johnson may or may not “own” Brexit. He certainly owns the responsibility to deliver it, or to deliver something that works.

His leadership will be unlike anything we’ve seen. But the consequences will be no joke.