BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

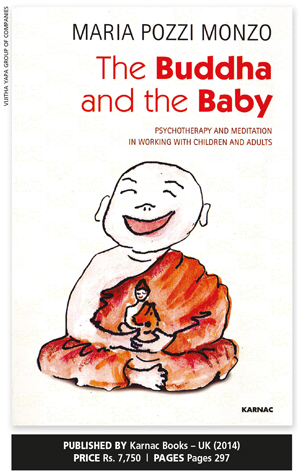

When a professional decides to write a book on psychotherapy and meditation, it is news especially when the focus is on Buddhist meditation. But when 18 specialist psychotherapists from around the world come together to contribute to a book on psychotherapy, and meditation for children as well as adults, what emerges is a treasure trove of insights.

Author Maria Pozzi Monzo – a child, adolescent and adult psychotherapist – has achieved this feat.

Fellow of the British Psychoanalytical Society David Black observes: “How naturally Buddhist understanding can harmonise with a psychoanalytic approach.” Black adds that he also enjoyed reading the many moving and idiosyncratic accounts of spiritual seeking in this book.

Psychoanalysis is described as a new concept that’s not even a century old while Buddhism dates back to the 5th century BC. In psychoanalysis, free association in the context of an analytical relationship offers a path to understand the unconscious mind while the practice of Buddhist meditation allows the unconscious to become conscious, which leads to awareness.

Rosalind Powrie is a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and Head of the Perinatal and Infant Mental Health Service at the Women and Children’s Hospital and the Women and Children’s Health Network in Adelaide. She treats mothers with depression who experience mental health issues.

Powrie talks about teaching mindfulness, which is a form of mind training where through meditation and mindfulness practices, one learns to be more aware and pay attention to the present – without judgement and with tolerance of one’s experiences. This involves mitigating the struggle in them, as well as suspending judgement and the related proliferation of thoughts.

Her practice involves weaving in more components around teaching self-compassion, as women often are the first to criticise themselves and become guilt-ridden. It is based on the idea that if you observe your experiences long enough with meditation, you’ll find that all experiences are in a state of dynamic flux and nothing remains the same from moment to moment.

This is a very hard concept for the human mind to grasp because people live as if things will remain unchanged.

It is easy to think that a foetus will grow by itself until it’s ready to be born. But Powrie says mothers who are stressed or depressed during pregnancy produce less cortisol – a hormone that counteracts stress and maintains hormonal homeostasis in the womb. The baby’s developing brain and physiology are affected if stress levels in a pregnancy are high.

She refers to some women who suffer antenatal as well as postnatal depression, and entertain thoughts about harming their babies. Powrie advises that if a mother can detach herself from those thoughts and resist struggling with them, they usually fade or lose their impact.

It was Martin Luther King, Jr. who famously said that power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anaemic. An important perspective is that while a mother is responsible for her baby, the infant is a separate being – and even though they are interdependent, both have to be recognised as separate beings.

The influence of Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh and his approach to therapeutic issues are also discussed in the book. On anger, he says that you have to get to know and understand the feeling, and then stand back from and transform it. His idea is that there’s no happiness without suffering.

Nhất Hạnh also talks about interconnectedness, and believes a flower and the rain that made it grow, the clouds that made it rain, the soil the plant grew in and the person who grew it are all interconnected and inseparable.

The book also has fascinating insights into experiences encountered by doctors. One such was the response of a little boy to the abuse he had faced from his father for a long time. The child had a strong sense of knowing that what his father was doing was wrong. Some questions are as follows: How did he know it was wrong? Where does the sense of what’s right and wrong come from?

In fact, the young child told Dr. Monica Lanyado, the founding course organiser of the child and adolescent psychotherapy training at the Scottish Institute of Human Relations in Edinburgh: “My dad didn’t teach me right from wrong but he’s still the only dad I have.”

The book also refers to the Buddhist explanation of the ‘monkey mind’ where your consciousness is unsettled, restless or confused. And the contributors try to help declutter it through meditation, to achieve clarity of thought and peace of mind.