BOOKRACK

British and Australian cricketers often turn to the printed word to tell their side of the story; but this is not the case in India, Sri Lanka or elsewhere in South Asia. Has anyone heard of autobiographies by Arjuna Ranatunga, Muttiah Muralitharan or Kumar Sangakkara?

I remember once asking Murali when he was at the height of his career whether we could do a biographical book if he was unable to pen his autobiography. He replied: “Someone is doing it.”

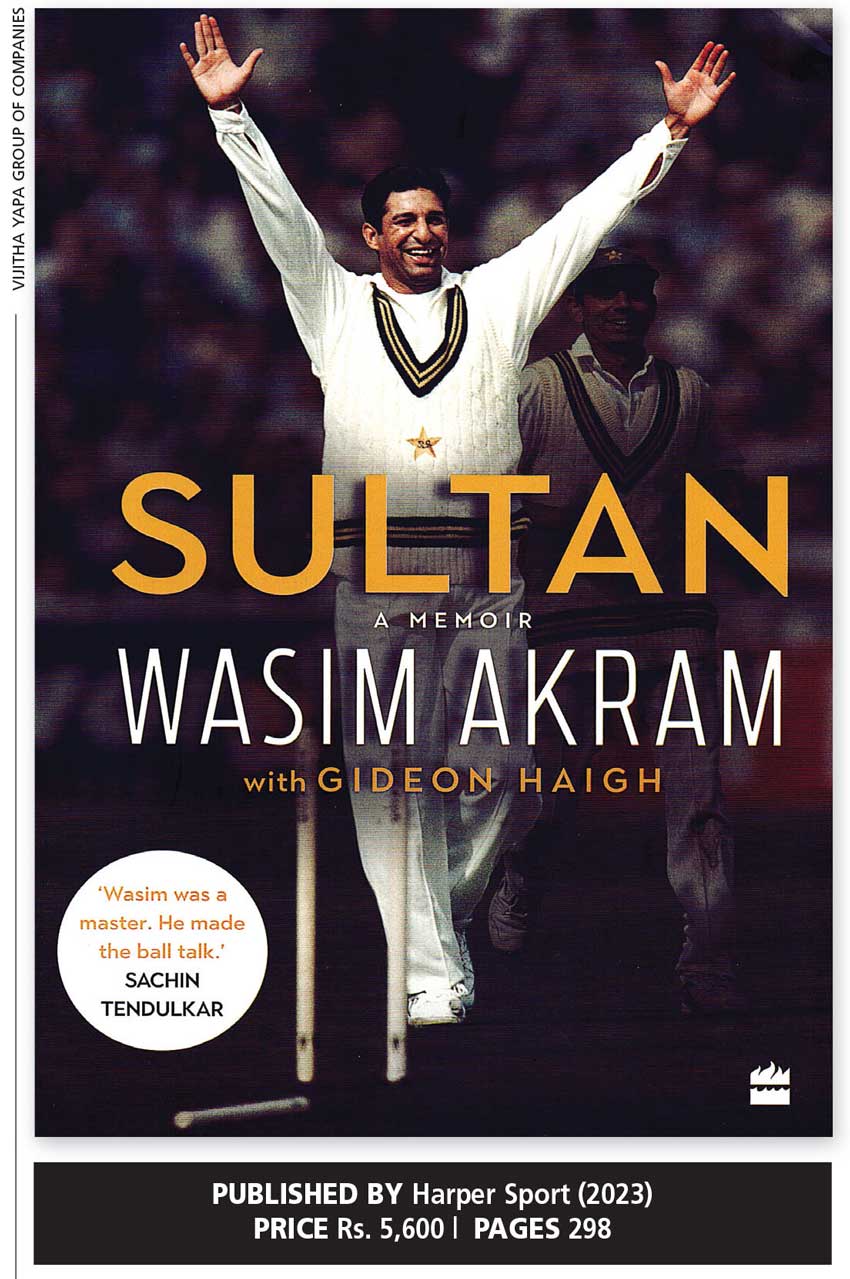

Alas, nothing has surfaced so far. So the decision by Pakistan’s Wasim Akram to work with Gideon Haigh to write his story is noteworthy.

Akram is recognised as cricket’s greatest left arm pace bowler. For over 20 years, he held centre stage with his idol Imran Khan. When Pakistan won the World Cup in 1992, Wasim was ‘Man of the Match.’ Sachin Tendulkar described him as a “master who made the ball talk.”

But it was not merely his bowling and batting that made Wasim one of the most talked about cricketers. The controversies surrounding him included ball tampering and match fixing, and he uses this book to give his side of the story.

He has delivered more than 80,000 balls in first class and List A cricket but Wasim says the game was never the problem as it was the simplest part of his life.

Bowling to greats such as “Viv Richards, Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara or batting against Shane Warne, Malcolm Marshall or Muttiah Muralitharan was child’s play compared to handling the expectations of my nation, the turmoil of my team and the machinations of my administration,” he says, in the opening pages of his book.

The Pakistan team has not been known for being consistent. Akram has a simple explanation for this as the country itself isn’t consistent. Nothing in Pakistan happens the same way twice and no one can rely on any institution.

He reveals that Pakistani cricketers were notoriously finicky travellers and recounts how in an under 23s tour of Sri Lanka, Haafiz Shahid was sent home because he could not bear the smell of coconut oil.

Wasim Akram conveys his views without batting an eyelid. “I was five when India sided with insurrectionaries in the east, leading to the breakaway of what became Bangladesh,” he says.

Imran Khan – with his overwhelming presence and looks – was his hero. “In 1985, he looked like a god: the face, the hair, the physique,” he recalls. It was Imran who took Wasim under his wing and helped him develop.

Wasim bats straight and doesn’t mince his words. He admits he loves hitting batsmen on the head.

He recalls how in England, he bowled to hit Ian Botham on the left foot.

Wasim says Botham was the opposition’s most dangerous player and his number one target. Australian great Justin Langer recollects: “Facing Wasim was like batting in fishing net. You couldn’t go anywhere. You couldn’t score. Basically, it was a nightmare… the smiling gentleman assassin was in a class of his own.”

The Pakistanis had a rough ride in England and the anger of English cricketers did not help. They were called cheats in the media and racial hatred was a key factor. But luckily, there were no incidents on the field between the players.

Ball tampering was another issue but no action was taken since the Pakistanis denied all accusations. The main issue was bowling reverse swing, which the English did not understand although it was later accepted.

Geoffrey Boycott was the only cricketer who came to their rescue by asserting that the two bowlers Waqar and Wasim “could bowl England out with an orange.”

But in Grenada, there was an ugly scene when the West Indian police swooped in on the players at a public beach and accused them of taking drugs. No one had seen them take drugs; but the police collected some stubs lying on the ground near them and accused them of being the smokers. They were finally freed after the prime minister intervened.

By then, Wasim Akram was involved in a major controversy because he confessed to drinking rum on the beach, which aroused the ire of Muslims.

What he reveals of captains being replaced at the drop of a hat and quarrels among directors who didn’t see eye to eye is similar to what’s happening to cricket in Sri Lanka today.

The rivalry in the Pakistan team led to a situation where prior to a tour of New Zealand, players refused to play under domineering Wasim as their captain. He tendered his resignation and Saleem Malik was appointed as the new skipper.

This tome also describes in detail Wasim’s battle with drugs, from which he recovered. It’s a book not only about cricket but the battle for the soul of a man who emerged triumphant after facing all the odds.