BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

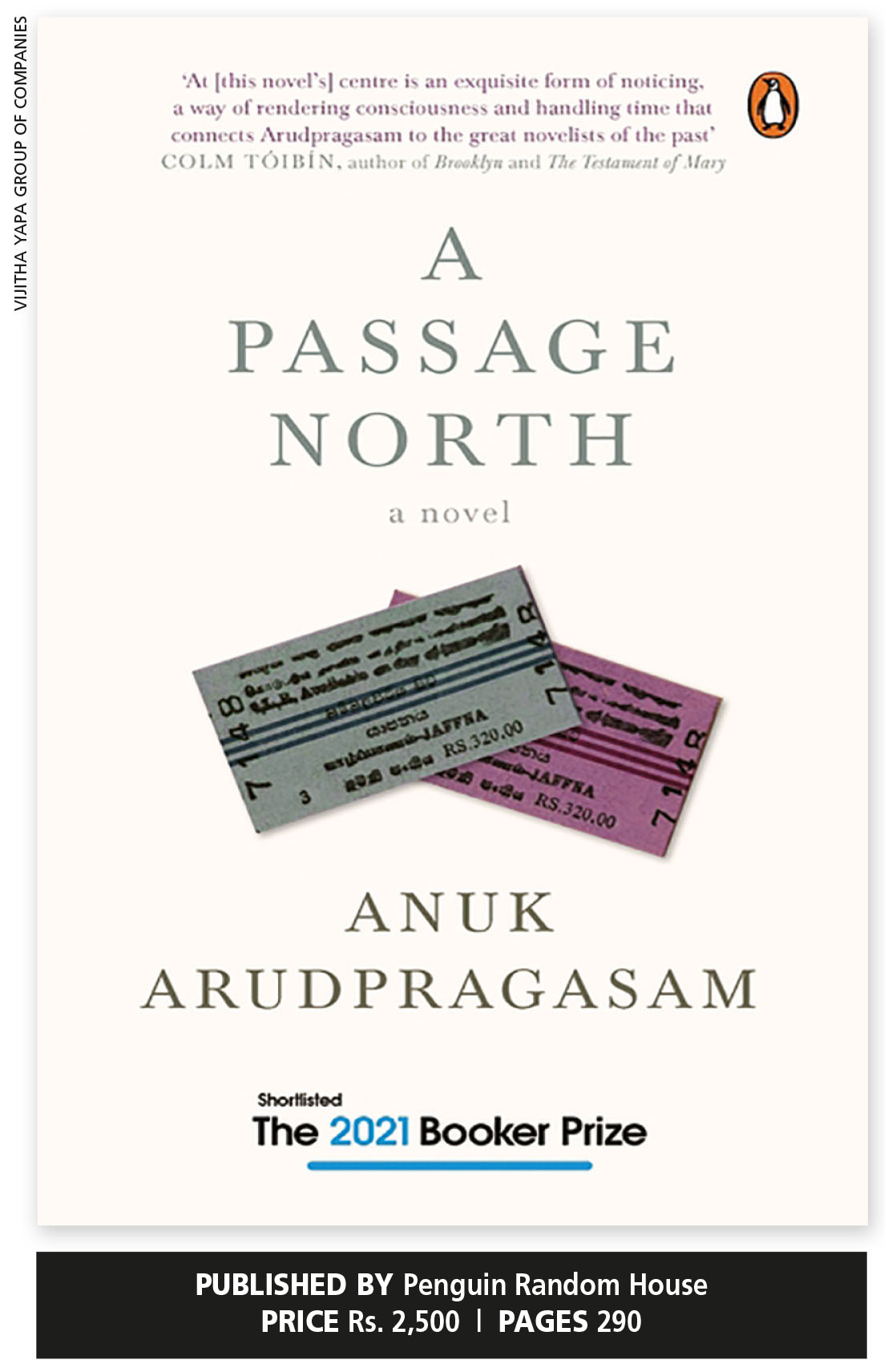

A Passage North has been shortlisted for the prestigious 2021 Booker Prize and the outcome will be known by the time this review appears in print. It is remarkable that this year has seen two Sri Lankans gain international recognition in their respective fields.

A Passage North has been shortlisted for the prestigious 2021 Booker Prize and the outcome will be known by the time this review appears in print. It is remarkable that this year has seen two Sri Lankans gain international recognition in their respective fields.

They are Anuk Arudpragasam in literature and Yohani Diloka de Silva in music with her hit song Manike Mage Hithe.

At a time when we are suffering not only due to COVID-19 restrictions but also from a shortage of essential food items, news of the achievements of these two Sri Lankans has brought some cheer and smiles to our faces.

Anuk’s book is strange to me as I have never read a novel where there isn’t a single conversation among the main characters. Further, it’s rare for a piece of literary work to have such extremely long sentences with many of them running into hundreds of words.

We were taught that brevity is important to retain the attention of readers and long sentences tended to confuse them.

One wonders whether Anuk’s inspiration comes from 1998 Nobel Laureate and Portuguese writer José de Sousa Saramago who didn’t shape his prose to fit traditional writing norms, and paid no heed to paragraph breaks and quotation marks.

The principal character is a man named Krishan and the story dwells on his relationship with his Indian girlfriend Anjum, his grandmother and her maid Rani from the north of Sri Lanka.

A perplexing relationship unfolds with Anjum who takes time off to be with him in Mumbai. They embark on a train journey thence from Delhi on separate beds in sleeper class, and Krishan learns about Anjum’s lesbian relationship with a woman who had dominated her life but finally let her go.

However, Krishan’s and Anjum’s relationship ends when they part company. But that’s only a sideshow to what Anuk is actually focussing on – i.e. the war between Sri Lanka’s armed forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

A weakness in the book is that it’s set in a part of the island that witnessed a bitter war. In any conflict, there are two sides; but according to Arudpragasam, all the atrocities were committed by the Sri Lanka Army (SLA) and not the LTTE.

For example, he writes about the railway line to the north being destroyed but doesn’t say a word about who did it.

This perspective will delight those readers in the West who are looking for misdeeds by armies vis-à-vis their own citizens to divert the spotlight from the atrocities committed by Western armies on other nations. So Anuk’s perceptions will help create a favourable milieu for Western judges when they decide who wins the award.

When writing on history, a balanced view would have strengthened his hand… even a single paragraph describing the real scenario would have helped readers better understand the true situation in Sri Lanka during its protracted armed conflict.

Krishan’s grandmother is a typical Tamil grandma who is immersed in her own world of religion and fables. The scene then shifts to the north where Rani sees her children die from injuries sustained from shrapnel that followed the explosion of an SLA bomb.

She is shattered by this experience, and needs electric shock therapy to find a cure for her trauma.

He encounters her in a hospital and decides that Rani may be cured if she’s given a fresh purpose in life… so he invites her to Colombo to look after his grandma. Their relationship is described in detail and a growing rapport between the women helps them both immensely.

Prejudices fall by the wayside but Rani still has her links with the north. She doesn’t return from one of her visits and her death as a result of falling into a well in her compound is a mystery. Was it suicide or something more sinister?

Krishan takes a long train journey to attend her funeral and detailed descriptions of those scenes take up many pages in the latter part of the book. Long sentences provide a glimpse into life in the desolate north of Sri Lanka – and the struggles of families living there are in sharp contrast to those who enjoy the green fields of the south.

There are no conversations in the book. All eventualities are seen through the eyes of the writer. After all, this is his perspective – it’s all that matters.

“Even if it was easier for most people to pass over these wounds in silence, suppressing their memories of the world they’d helped construct and the violence that had destroyed it, even so people would remain who insisted on remembering,” Anuk laments.

This young writer has demonstrated his narrative skills in the book he has written – and more will be expected from him.