BANKING SECTOR

BANKING ON GREEN AMBITIONS

Samantha Amerasinghe asserts that banks should be more engaged as climate actors

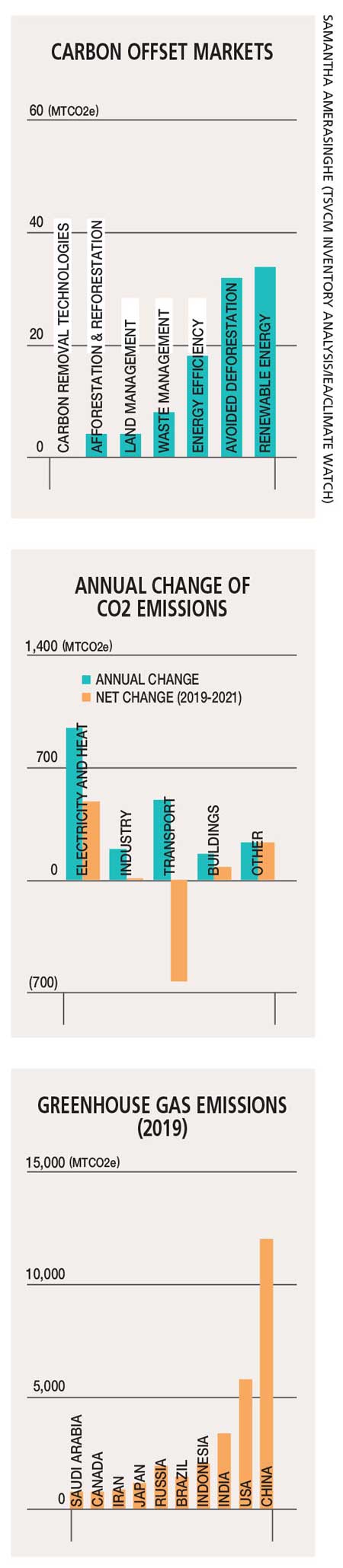

A green wave is now sweeping the financial services industry. Recently, banks and other asset management entities have begun acquiring businesses that are playing an active role in the booming market for carbon offsets to advance their climate change efforts.

Such moves should help accelerate the pivot away from fossil fuels in favour of clean energy at a time when the world is becoming more worried about extreme weather events – such as the deadly deep freeze across the US, Canada and Japan at the end of last year.

With governments putting more pressure on the private sector to limit greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the world’s largest corporations have turned to carbon credits to offset their environmental footprints.

This market will be worth more than US$ 1 billion in the next few years.

Carbon offset markets don’t lessen or deter activities that add to global warming but neutralise them with projects that seek to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

A carbon credit is a tradeable certificate that stands for one tonne of carbon dioxide (tCO2). It represents carbon that has been avoided, reduced or sequestered through a project and can be purchased as a means of offsetting emissions elsewhere.

This means that emitters lack incentives to change their behaviour and it’s difficult for banks to hold the organisations they deal with accountable.

While carbon credits are a measurement unit to cap emissions, carbon offsets can be considered as measurement units to compensate organisations for investing in green projects or initiatives (natural or technological) that remove emissions.

Carbon offsets help businesses compensate for emissions generated elsewhere through their operations by planting trees or buying credits and so on. These are designed to allow businesses to pay a small sum in exchange for removing carbon from their balance sheets.

But are these transactions letting polluters off the hook?

Sceptics argue that these offsets function like an accounting manoeuvre that allows more GHGs to enter the atmosphere. Timing is the key concern. Many renewable low quality offsets came into being when solar and wind power became the cheapest sources of energy in many countries.

Therefore, selling offsets for small sums to support the economics of renewables doesn’t provide any real benefit if it’s already cheaper than building new coal or gas power plants.

Banks face a dilemma due to their ongoing support for fossil fuels. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, more than three dozen banks globally have lent and underwritten US$ 2.7 trillion for the fossil fuel industry.

The financial services industry has long been a target of climate activists who are opposed to its backing of carbon heavy projects. Global banks are well aware that they can’t meaningfully address the climate crisis without curtailing the expansion of fossil fuels. But the solution is not that simple.

Banks aren’t ready to walk away from fossil fuels, and will need resources such as oil and natural gas, until such time as affordable and low carbon alternatives are developed to meet global energy needs.

A contentious topic at the recently concluded COP15 forum (the biodiversity focussed counterpart to last November’s COP27 climate summit) was the use of biodiversity credits (similar to carbon credits) – a trend that’s catching on fast.

Critics warn that these credits could allow for pervasive greenwashing. Greenwashing involves making unsubstantiated claims to deceive clients or consumers into believing that one’s products have a greater positive environmental impact than they actually do.

Furthermore, biodiversity credits are also deemed controversial over the trade-offs they may require.

To build an airport for example, a developer might seek to use bio-credits to offset the destruction of wetlands (inhabited by endangered native birds) by nurturing a similar environment nearby.

Many asset management entities are falling short over the apparent hypocrisy in their use of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment factors.

There are many flaws in the carbon offset market including hefty cuts to brokers and questionable corporate claims. Biodiversity credits also lend themselves to greenwashing due to the breadth of projects that can be deemed to support biodiversity – wetlands, coral reefs, rainforests etc.

Given the strong corporate appetite for offsets of every kind (i.e. carbon or biodiversity) however, and the lack of stringent rules and guidelines, greenwashing risks in this nascent sector will be a given.

Regulators are focussing on ESG too. Financial services institutions are well aware that the moment of reckoning has arrived.

One obvious solution to moving towards a net zero emissions goal – albeit a complicated one – is to cut off credit to emitters. Boosting advisory services for environmental governance and adding loan covenants to make sure borrowers stay below emissions thresholds would also be beneficial.

The big and bold announcements by banks to be increasingly engaged climate actors are welcome – but they still have a long way to go to be credible.

Leave a comment