2022

First Sri Lankan Citizen to Win the Booker

Novel catharsises island’s traumatic past

Sri Lanka’s place in the sun under the warm, benevolent light of the Booker had been a long time coming. Since 1992, when Sri Lanka-born Michael Ondaatje first made the cut with his creative and complex novel The English Patient, there had been a sense that the island’s star was rising in the planet’s literary orbits.

Yet, it would be 30 years later that Sri Lanka’s gift to Canada would win the Golden Man Booker Prize in 2018 when his offering to bibliophiles was adjudged the ‘best of the Bookers’ in its long and illustrious history.

Still, there was a sense that a Sri Lankan per se – a born and bred islander who had not left our fair shore even if the grass was so much greener on ‘the other side’ – had not stepped up to the plate.

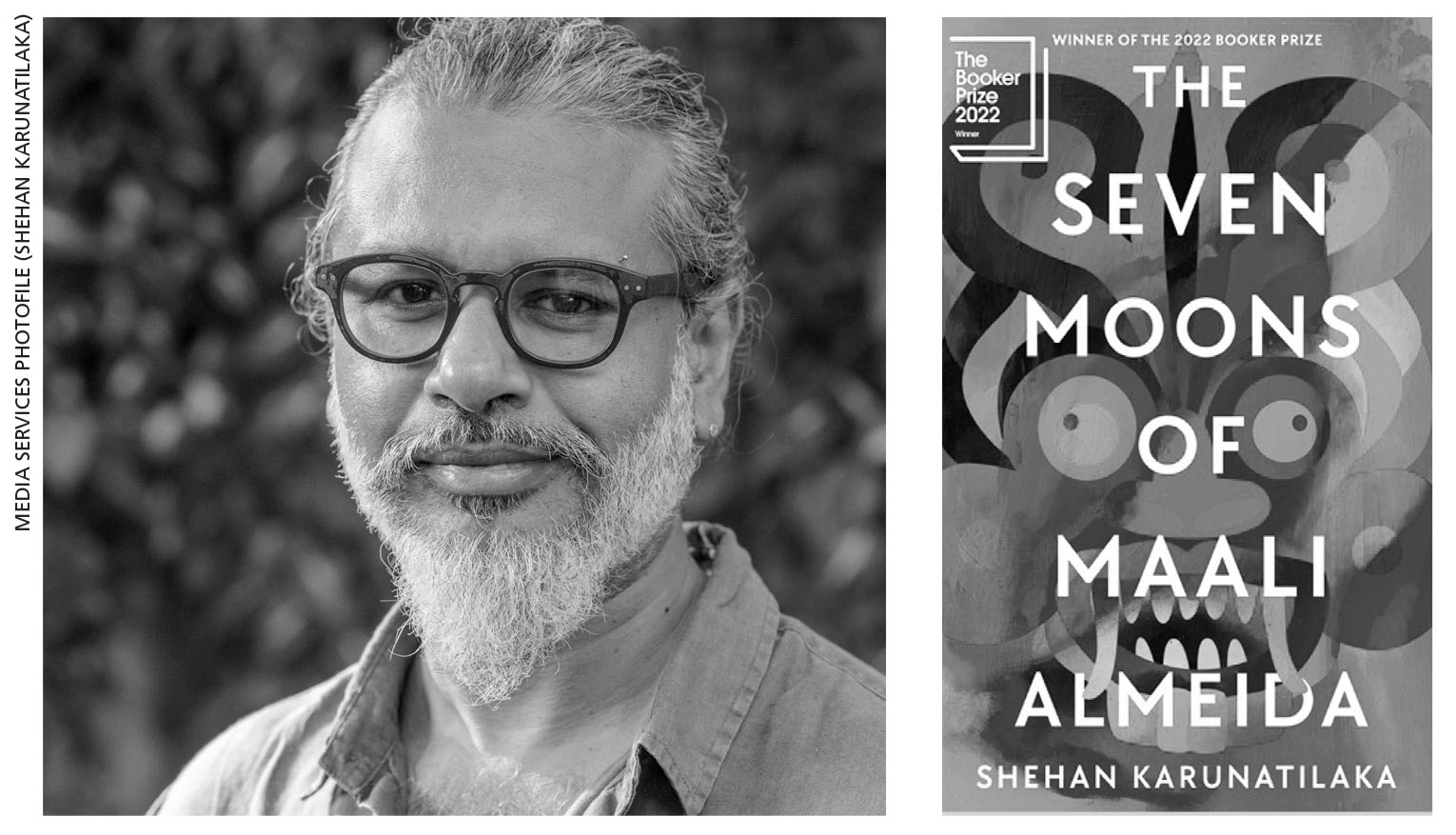

Enter Shehan Karunatilaka – erstwhile advertising copywriter and onetime guitar playing member of a band named Independent Square – to clinch the title in 2022.

Described as being “one of Sri Lanka’s foremost authors,” the bearded and ponytailed writer had first emerged from the shadows to dominate the spotlight with his maiden novel Chinaman. That dazzling debut marked Karunatilaka’s arrival on the literary scene, going on to win the local Gratiaen and Commonwealth Book Prizes in 2011.

Fast forward 11 years after Chinaman wowed readers to a “riotous, funny and heartbreaking South Asian epic” that had been seven years in the making – including an editorial update to Chats with the Dead (the novel’s original title in 2020).

Now renamed The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, the novel was ready to tickle, titillate and traumatise. Of course, after securing for its creator a prizewinning haul of UK£ 50,000!

A deeply disturbing fantasy about the afterlife, it’s a creative masterpiece that Karunatilaka says he began thinking about in 2009, “after the end of our civil war when there was a raging debate about how many civilians died and whose fault it was.”

But the author admits: “I wasn’t brave enough to write about the present – so I went back to the dark days of 1989… [when] there was an ethnic war, a Marxist uprising, a foreign military presence and state counterterror squads.”

Karunatilaka recalls it being “the darkest year in my memory” … “a time of assassinations, disappearances, bombs and corpses.”

Out of that era of death and despair came a bright, shining book that the panel of judges described as “a searing, mordantly funny satire set amidst the murderous mayhem of a Sri Lanka beset by a civil war.”

It is a small but by no means insignificant saving grace for a nation state that is demonstrably bankrupt in more ways than one. And its Sri Lankan audiences’ mixed reactions to it so far – adulation, ecstasy, irritation, outrage, undying fandom – tells a tale about us all, still in the making.

Out of that era of death and despair came a bright, shining book that the panel of judges described as ‘a searing, mordantly funny satire set amidst the murderous mayhem of a Sri Lanka beset by a civil war’