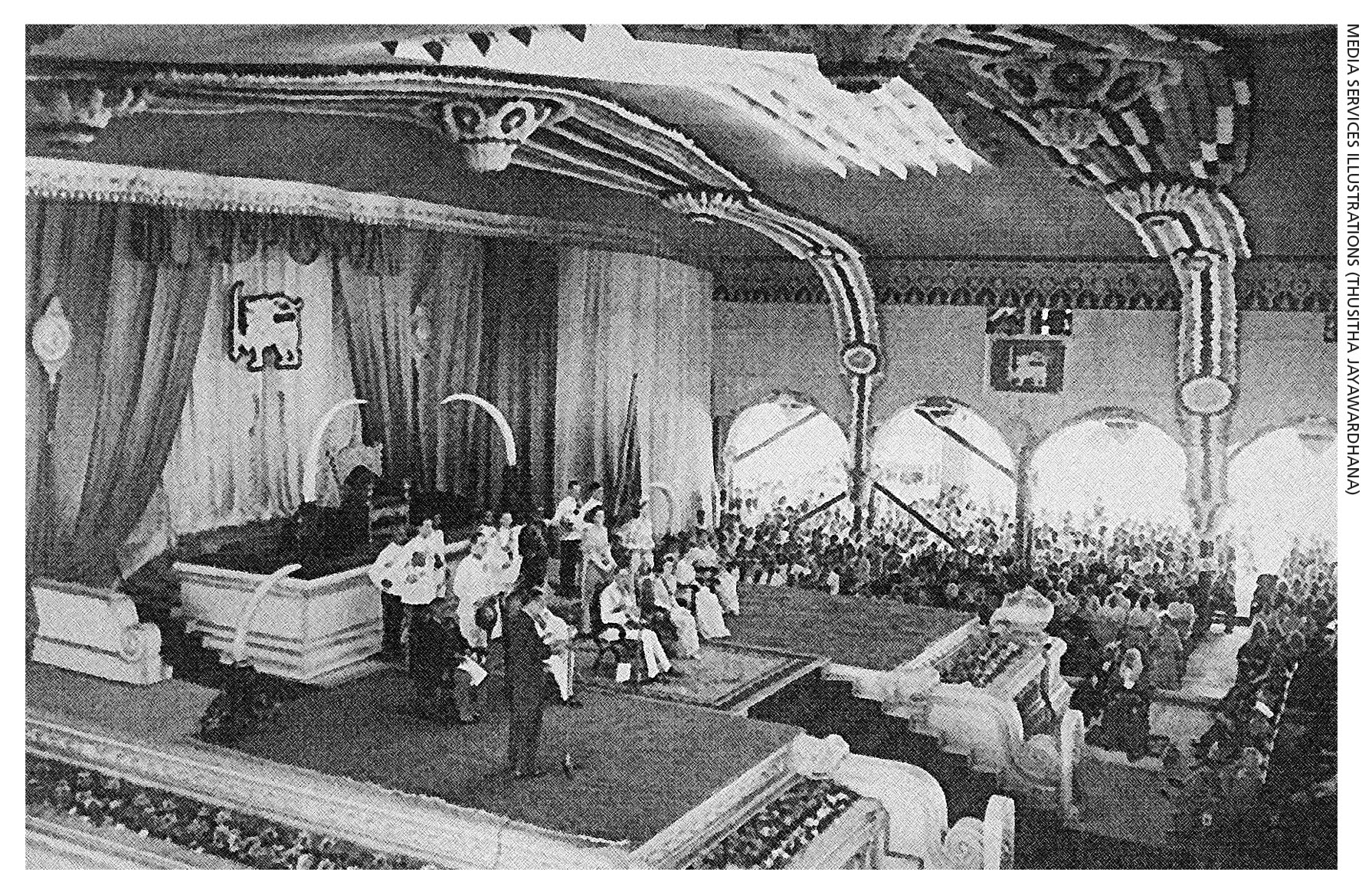

1948

Dominion Status a Double-Edged Sword

Freedom from Britain didn’t mean liberty

Ceylon’s independence from the British Empire did not come at the stroke of a pen at midnight on 3 February 1948. It was the culmination of a largely peaceful protest movement that had steadily gathered steam since the turn of the 20th Century.

Yet, the dawn of a new day on 4 February did not necessarily signify true liberty for the sons and daughters of the tropical isle that had endured the yoke of colonialism for 443 years (1505-1948).

Rather, it was a subtle shift in the power balance that had prevailed since the British conquered the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815, having had the Dutch cede the country’s maritime territories to Britain, which ‘ruled the waves’ under the Treaty of Amiens (1802).

So momentous was the peaceful transfer of power from a Britannic colonial administration to native rule that the ramifications of dominion status (1948-1972) were not immediately realised or acted upon.

For one, and despite the enactment of the 1947 constitution that introduced a bicameral legislature, which returned the franchise to the Ceylonese to elect their legislature and senate, there was a Governor-General who – as the head of state – represented the British Monarch (in 1948, it was King George VI; to be succeeded by his daughter Queen Elizabeth II, who was still on the throne when Ceylon became the Republic of Sri Lanka in 1972).

For another, in instances where the new constitution was silent in matters pertaining to governance and so on, Ceylon’s native rulers were constrained to relapse to conventions once observed by the British, and still in force in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in the Commonwealth – a prerogative exercise through the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Britannia still ‘waived the rules.’

Last but not least, as a result of the governing party being drawn from progeny of the old imperial ethos – educated, English-speaking and largely Western orientated – the national culture of the new dominion did not reflect the interests, aspirations or worldviews of a majority of newly independent Ceylonese in the main.

The dawn of a new day on 4 February did not necessarily signify true liberty for the sons and daughters of the tropical isle that had endured the yoke of colonialism for 443 years