Will Gotanomics reform our SOEs?

As a country, Sri Lanka has seen its fair share of challenges. Since Independence, apart from the 1977 economic reforms, our economic reform agenda has been mediocre. Instead of taking bold decisions to improve competitiveness and keep pace with global trends, we adopted an inward-looking approach. We boast about our natural resources and claim that we are the pearl of the Indian Ocean but have not introduced the reforms needed to convert those resources into economic gain. Sri Lanka’s debt is a little over 82% of GDP (1), and rises to a 100% of GDP if one includes private sector loans. In other words, our borrowings exceed what we produce as a country each year. Poor economic growth, averaging 2.6% exacerbates the problem.

In this economic backdrop, Sri Lanka has decided to place its trust in a President who promised significant economic reforms, a mix of tax reforms, governance reforms, and some subsidies with the objective of bringing relief to the people.

The President has walked the talk during the last few weeks. A board has been appointed to select the heads for Sri Lanka’s loss-making state enterprises, and sweeping tax cuts have been provided to encourage all businesses and individuals to boost economic growth. Public conversation centres on whether these reforms are practical and the question of the day is: “Will this work or is it just a political gimmick for the upcoming parliamentary election?”

At surface level, hiring professionals based on merit will improve fiscal discipline and accountability in our state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The tax cuts will drive the supply side of the economy to boost growth, at least in the short run. However, this article discusses a few challenges to SOE reform in particular.

1. Challenge of recruiting the right people to SOEs

The appointment of a well-experienced board to appoint members to head SOEs and opening calls for applicants to include Sri Lankans living overseas is a step in the right direction. But the question that remains is whether our labour market has the capacity to fill positions for a very long list of SOEs. Turning loss-making SOEs around would require substantial reform. According to Advocata, the number of SOEs including subsidiaries and sub-subsidiaries, amount to 527. Even if you take a good 250 which are the critical institutes and appoint a minimum of three members to a board, this brings us to a total of 750 senior-level appointments. This is nearly a factory of people with a decent level of business acumen who are able to take some hard calls. Even paying market rates and finding people will be a mammoth task given the soft skill shortages we have in the country. Even starting with the 54 strategic SOEs would be a challenge.

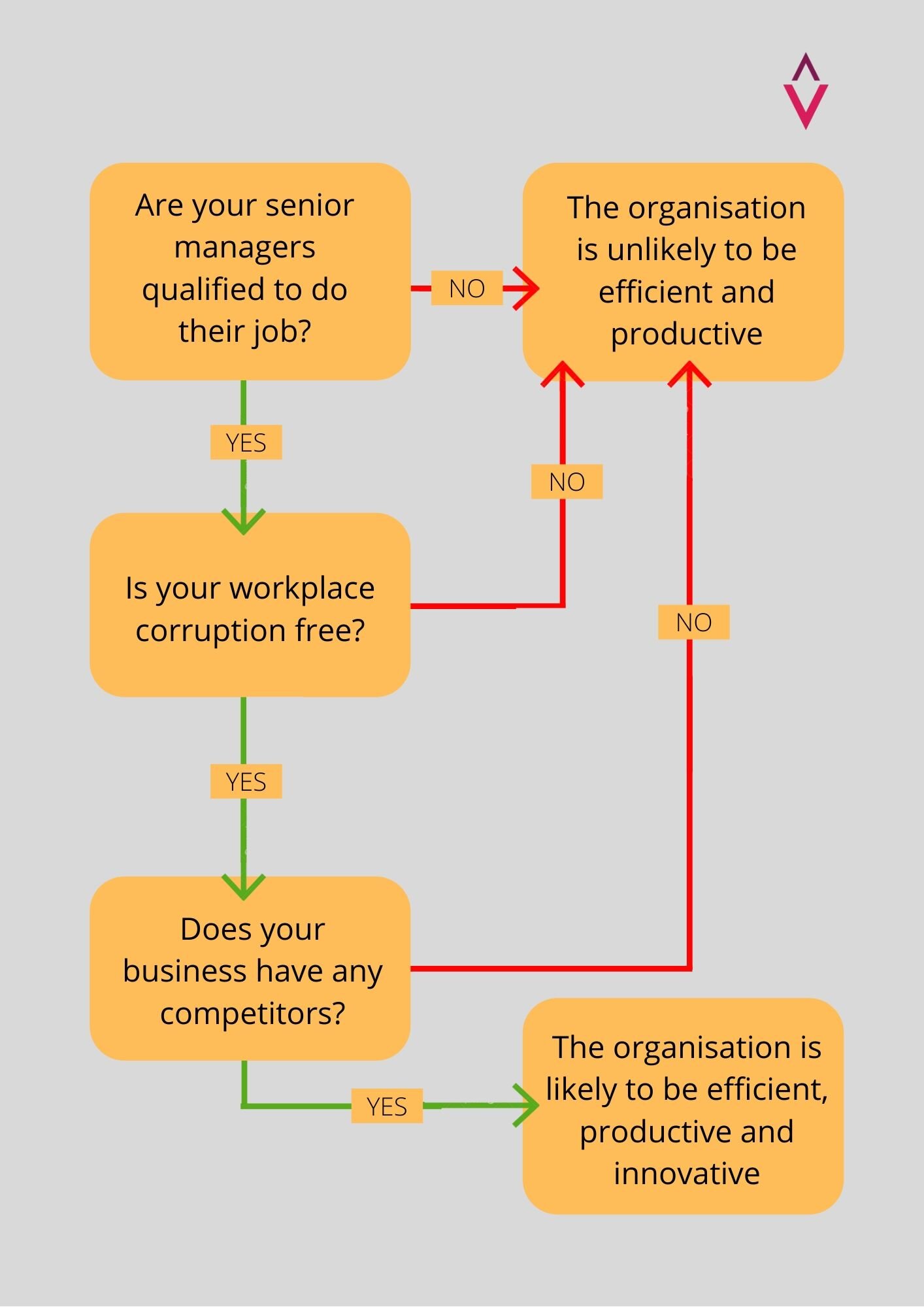

Converting loss-making institutes which have strong links to trade unions is a harder job than getting a start-up off the ground. On the flip side, the Ceylon Electricity Board, SriLankan Airlines, Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and Sri Lanka Transport Board account for the largest losses annually. The boards of these gigantic loss-making institutes will be crucial. The Government would have to leave political capital aside and support the reform process of these institutions if they are truly committed to turning them around. These four SOEs should be at the top of the reform agenda and the Government should not dilute its focus just because they will be challenging to reform. In the appointment process, the next step is to avoid hiring unqualified people who will continue the system of interference. To ensure this does not happen, it is key that the selection process is transparent.

2. Challenge of converting some loss-making SOEs which are beyond efficiency and the performance of senior management performance

Some of these SOEs are clearly beyond just the capacity of the management team. Some require further investment if they are to be turned around and the Treasury’s ability to do so is questionable. These entities have been bleeding out money at the expense of the Treasury and given the expected drop in revenue, further investment seems increasingly unlikely. Some SOEs need to cut down the cadre drastically if they are to even breakeven, and Voluntary Retirement Schemes (VRSs) should be considered in the restructuring process.

The manifesto of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa is clear – privatisation is off the table but the consolidation of certain nonstrategic SOEs is still a viable option. However, most of the SOEs will not be able to turn around solely on efficiency increments. The multitude of organisational layers and market drawbacks mean that effective reform will require time, investment, technological expertise, and serious revamping.

3. Overcoming corruption in the bureaucracy and poor level of knowledge in subject content by senior government officers

It is true we have genuine, knowledgeable civil servants but undoubtedly the numbers are few. In SOEs the symbiotic ecosystem of corruption of bureaucracy and board-level appointees is no secret. The effectiveness of the board depends on whether or not the bureaucracy supports the reform. Simply, they can make or break it. The ability for boards to intervene in the bureaucracy is uncertain. The pervasiveness of corruption is clearly a result of political appointments provided by consecutive governments for party supporters and henchmen. Given this, it is not only difficult to find clean bureaucrats, it is almost impossible for those individuals to navigate a system that is geared against them.

4. Challenge of ensuring fair competition with SOEs

Some SOEs are simply monopolies run by the Government. Sri Lanka Ports Authority is one example and there is no reason for them to make losses. It is important to re-evaluate the actual profit-making capacity in Government monopolies. In realistic terms only, the profits really do not showcase their economic gains since they do not operate in a competitive market place. At the same time, there could be some areas where the Government needs to operate even at a loss due to public interest and the absence of the private sector. Operation of buses in rural areas is one such example. The challenge would be transforming and maximising the profits of SOEs which are already in a competitive market place while ensuring a level playing field for the private sector.

For example, there are many players including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the modern retail market due to urbanisation and the growing middle class. Government-owned Sathosa is also competing with them and the past record shows that some concessions are provided only to Sathosa, which are not provided to private businesses. If the state procurement process shifts to get supplies only from Government institutions, just the numbers of higher profits or lower losses, it will be a number gimmick and will not create meaningful growth. The same request has come multiple times by some parliamentarians due to lack of knowledge on the overall economy to get the supplies only from Government entities for Government institutes. Such measures will lead to higher corruption and discourage the private sector.

In other words, the board, to appoint new members for SOEs should follow up with a series of guidelines to ensure that principles of fair competition are upheld, that key performance indicators (KPIs) are monitored, performance contracts put in place, and that an effective incentive structure is put in place.

The President and the new Government should equally focus on continuing the investigations on corruption and misallocation of money so the new appointees will take it as a “responsibility than a reward” as per the President’s line of thinking.

In summary, the President’s decision to appoint a committee for the board appointments is a step in the right direction but is just an entry to the complicated problem. To convert the organisations, another series of reforms should follow at the earliest, as time is running out with an anticipated revenue loss, tax reforms, and our SOEs; an ICU patient constantly bleeding for few decades.