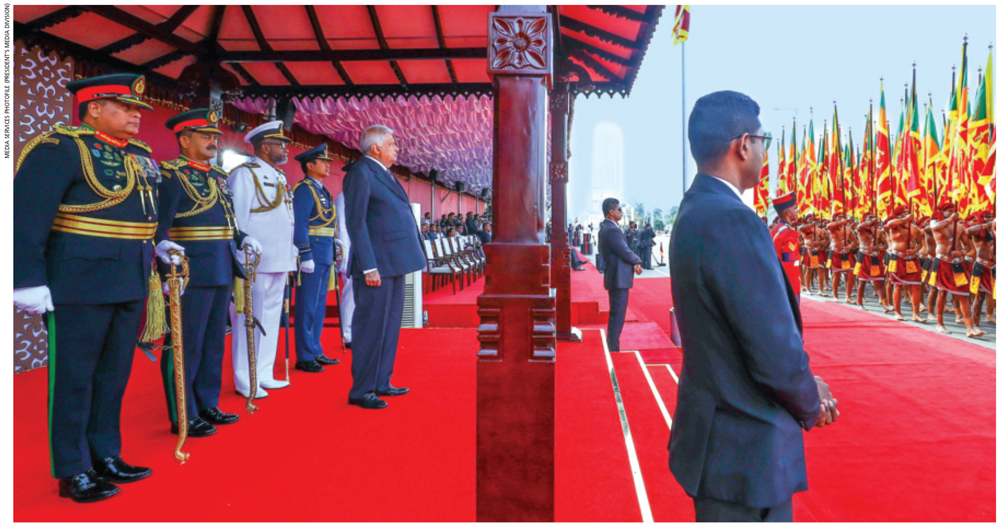

Sri Lanka commemorated 76 years of independence recently with a sense of déjà vu in the traditional ceremony at Galle Face. It’s customary for administrations to major on military arsenals.

VIEWPOINTS

BIG BROTHERS AND RED COM

Wijith DeChickera feels a strong current across the Palk Strait and wonders if it is a new wave or only so much water under the bridge

This year – despite national debt restructuring and attendant hardships – was no different save paratroop demonstrations.

Regimes ride hard on remembering what matters to their electoral stakeholders while opportunities for national reconciliation slip by like faulty parachutes.

While governments march to the same drum – jingoistic, atavistic and nationalistic – year after year, the cynosure of all eyes these days are two major polls before year end.

Meanwhile, President Ranil Wickremesinghe has set his sights on making Sri Lanka rank among developed nations.

In a speech at a United National Party (UNP) rally last year, he said: “The country should not focus on short-term politics; instead, we should think about the future, specifically 2048, and work towards making Sri Lanka a developed country.”

Despite critics who felt it was unrealistic, the president – elected as chief executive not through the ballot but by a parliamentary poll and who may seek to consolidate his office at the presidential election this year – detailed in June 2023 his ‘National Transformation Road Map’ to achieve this laudable (yet, elusive in 75-plus years) goal.

To silence detractors who claim such objectives are unachievable without practical policy frameworks, Wickremesinghe outlined foundational premises of his 2048 oriented development project resting on four pillars: fiscal and financial reforms; investment drives; social protection and governance; and state-owned enterprises (SOE) transformation.

Although his road map has strengths such as ‘halting unnecessary expenditure,’ ‘streamlining government activities to reduce costs,’ ‘designing cost-effective [state] operations,’ and ‘leveraging automation and digitalisation to reduce costs while delivering quality services,’ it shows structural weaknesses – a refusal or reluctance to dismantle bricks in the wall of corruption to have the edifice of waste, mismanagement and bureaucracy crumble.

However much the project constructs brighter futures on the building blocks of ‘an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) regarding fiscal and financial reforms,’ ‘promoting investments’ leveraging ‘collaboration between the public and private sectors’ and addressing ‘social safety net concerns’ with ‘public engagement,’ it has no milestones to mark the past 10 years’ misgovernance.

Paying lip service to three main demands (combatting corruption, protecting the poor and vulnerable sections of society, and ensuring transparency in government practices and actions) expressed by the Sri Lankan people over the years, Wickremesinghe’s transformational plan remains silent on recovering national assets allegedly squirrelled away overseas by unscrupulous politicos of yesteryear.

Other than avowing to ‘work actively’ to meet its targets, the road map detours around the elephant in the room – a pressing need to learn from lessons of especially the past five years of misrule.

Perhaps even recoup opportunities lost since a new hope in 2015-2019 fizzled out under realpolitik, and ensure social justice is dispensed to perpetrators of serious policy lapses and financial crimes leading to national bankruptcy.

The leader of Sri Lanka’s Grand Old Party (GOP) is not averse to looking to the halcyon days immediately after 1948, loath as he seems to look back in anger at 2019-2022.

Speaking of states serving politicians, it was interesting to note the recent visit of National People’s Power (NPP) supremo Anura Kumara Dissanayake to India – at the Indian government’s invitation – where he met high-ranking officials including Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar.

While it is not unusual for our northerly neighbour to keep a ‘Big Brotherly’ eye on goings-on across the Palk Strait, the invitation to a leader of a radical party – the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) is the engine of the NPP, after all – that has historically opposed any form of Indian interventionism in Sri Lankan affairs, and took up arms against the state and the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in the troubled and violent late 1980s, seems odd to the say least.

Irony aside, India’s modus operandi has been to reach out proactively to Sri Lankan aspirants to highest executive office when their popularity at home sends out strong signals across the region.

That billion plus people nation’s interest in and the importance it places on Sri Lanka’s geopolitical chops in relation to Indian Ocean security necessitates a strategic reaching out to parties that may one day form a government in its neighbour state.

Is the writing on the wall and the banns published? Or will the ‘always the bridesmaid, never the bride’ be left at the electoral altar yet again?

Given the JVP’s track record and present vacancy in strategy (no named leadership to key portfolios, distressing vagueness on economic policy save ambiguous noises about negotiating with the IMF), perhaps voters will never have to ‘get it to the church’ on time...

This content is available for subscribers only.