MONETARY POLICY

THE HEADWINDS TO GROWTH

Samantha Amerasinghe assesses the impact of financial conditions on global growth

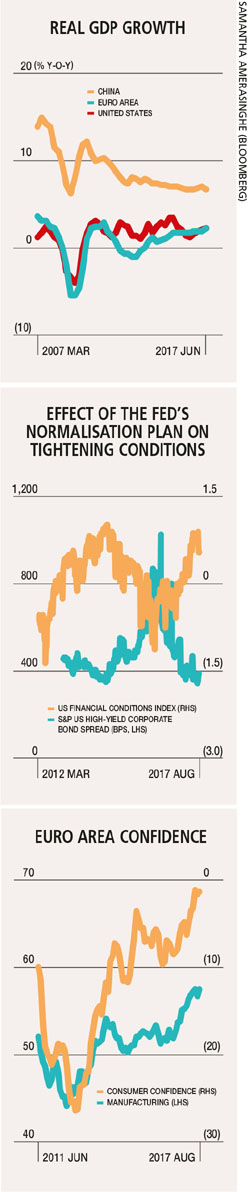

In its latest World Economic Outlook Update (July 2017), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) states that the cyclical recovery in the global economy continues and growth remains on track with worldwide output projected to grow by 3.5 percent this year and 3.6 percent in 2018.

These projected global growth rates are below pre-crisis averages especially for most developed economies and indeed, also for commodity exporting emerging and developing economies.

Many developed economies face headwinds to potential growth from weak investment flows, ageing populations and low productivity while financial stability risks are the main concern in many emerging economies. And the risks to the global growth forecast remain skewed to the downside over the medium term.

Rising valuations in equity and other asset markets, against a backdrop of low volatility and high policy uncertainty, could imply that a market correction is imminent. This could dampen both growth and confidence.

The fact that policy is more supportive in China with strong first half growth has provided policy makers the space to focus on deleveraging and monetary tightening that come with rising downside risks over the medium term.

Monetary policy normalisation particularly in the US could trigger a sooner than expected tightening in global financial conditions. Other risks include inward looking policies such as US trade protectionism, which would impact growth over the longer term. The upside is that political risk in Europe has diminished so the cyclical rebound could be stronger in the region.

Given the conflicting signals on growth and inflation, many were hoping that this year’s gathering of the world’s central bankers and economists at the US mountain resort Jackson Hole would provide some insights on important policy issues facing central banks.

The debate over US monetary policy has focussed for some time on whether policy makers should take their signal from falling unemployment, which has strengthened the case for rate hikes or sluggish inflation.

But no fresh clues on the next policy moves were forthcoming in speeches by Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Janet Yellen or European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi. Instead, both central bank leaders opted to focus on financial regulation and free trade, thereby keeping their policy options open.

As the economic outlook strengthens in the United States, the Fed will continue to gradually normalise its monetary stance.

Since its December 2015 rate hike (the first in nine years) that had a benign impact, the Fed has abandoned quantitative easing (QE), increased rates three times and signalled its intention to proceed with reducing the size of its US$ 4.5 trillion balance sheet without derailing growth or destabilising markets.

We can expect US Fed balance sheet normalisation to begin in October with another 25 basis point rate hike in December.

In the meantime, ECB policy makers remain concerned about a premature tightening of monetary conditions especially given the rise in the trade weighted euro in the past three months.

Surveys suggest that the Eurozone’s economic expansion has strengthened and sentiment has improved. This should support policy makers’ confidence that inflation will eventually reach its ‘close to but lower than two percent’ target. The current strength of the euro is keeping inflation low.

So Draghi is likely to reiterate that accommodative monetary policy will be needed to improve inflation dynamics in the Eurozone. Details on its QE tapering plans are unlikely to be forthcoming until the ECB’s 26 October meeting.

In China, headwinds may contain economic growth in the second half of this year and beyond. We can expect the People’s Bank of China to balance the need for deleveraging with the desire to maintain steady growth ahead of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China on 18 October.

Despite real activity surprisingly on the upside under tighter financial conditions, we can also expect GDP growth to slow to 6.7 percent year on year in the second half as policies may turn less accommodative and property market tightening measures could weigh on investment.

Resilient consumption and service sector growth could help curb the downside. We can expect the People’s Bank of China to maintain its tightening bias, guiding credit growth lower with policy rates increasing by 10 basis points in the fourth quarter of this year to keep pace with Fed

rate hikes.

The IMF revised its US growth forecast for 2017 in its July update to 2.1 percent (from 2.3%) and 2.1 percent (from 2.5%) for 2018 on the assumption that fiscal policy will be less expansionary than previously anticipated.

The lower 2017 forecast partly reflects weak first quarter growth. But US economic growth has picked up in the second quarter, driven by household spending and firmer investment in a sign that the recovery is maintaining its momentum despite a lack of policy progress in Washington.

The preliminary reading indicated GDP rising by 2.6 percent over the period, rebounding from a sluggish 1.2 percent increase in the first quarter. This strong GDP reading for the United States comes amid signs of a stronger global upswing that is increasing the likelihood of the Fed withdrawing more of its stimulus in the second half of the year.

And the policy moves of major central banks will be closely monitored for signs that global financial conditions might be tightening more rapidly than anticipated.