GREEN ARCHITECTURE

EXCLUSIVE

INITIATING SENSITIVE DESIGN DIALOGUE

BY Shatotto – Architecture for Green Living

Bangladesh’s perspective on public/community space

The capital city of Bangladesh, Dhaka has fallen prey to an urban disorder due to unplanned development and rapid urbanisation. This is largely caused by the absence of effective city planning and vain policy-making. The once glorious city with admirable heritage has given rise to uninhabitable public spaces, which have escalated with population growth, chaotic traffic, waterlogging, dilapidated roads and mosquito infestation.

The parks and playgrounds, which used to be the lungs of the urban fabric, have lost their essence. As a consequence, the quality of living has deteriorated immensely and Dhaka has lost its proverbial green.

In 2016, the Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) launched the Jol Shobuje Dhaka project to revitalise and rejuvenate 31 parks and playgrounds with different architectural firms participating under the leadership of Prof. Rafiq Azam. Children, the youth and the elderly were identified as the primary user groups for this endeavour, as these open spaces would provide them with the necessary space for physical activities and to find tranquillity.

Shatotto’s philosophy

Azam believes that there is a close relationship between humans society and nature, strongly built on trust and respect. The philosophy adopted here is to devise a holistic, inclusive and sustainable approach to the development of design.

The design philosophy that provoked the revitalisation of this urban space was to allow the community a sense of ownership and responsibility towards their own green space.

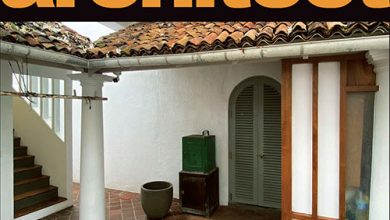

RASULBAGH SHISHU PARK, Azimpur, Dhaka

Prelude

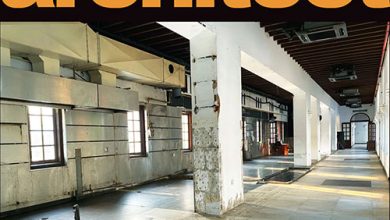

Rasulbagh Shishu Park, situated north of the new Azimpur Graveyard, was a long earned result of severe neglect and poor design. Nestled within the Rasulbagh district, the isolated park lacked direct access to primary roads. Surrounded by residential buildings, narrow alleys that were barely three feet wide served as the sole pathways for locals to reach it. Entry points were limited to the southwest corner and northern wall, adjacent to a congested road, and lined with makeshift shops and tea stalls.

The park itself bore the scars of neglect: withered grass, cracked graffiti covered walls and malnourished trees. An abandoned three storey veterinarian clinic occupied the western edge while an active mosque stood in the southeast corner, which was accessed through the park by locals for religious activities. An old Banyan tree, a site of traditional festivals and mourning of the deceased, resided in the northwest corner, still serving its purpose.

Despite being labelled a ‘shishu park’ – i.e. a children’s park – it lacked play equipment and was stained by indecent activities, preventing children from visiting it any longer. Recognising the dire conditions, it became evident that remedial action was necessary to rectify and safeguard the park from further deterioration and decay.

Intervention

The plan was implemented in two distinct stages, each addressing different sides of revitalisation. The initial stage concentrated on the physical restoration of the park while the subsequent phase emphasised community engagement and social integration.

In the first stage, the primary objectives were repairing the park’s infrastructure, and enhancing accessibility, usability, functionality and aesthetics.

The physical connection between the park and its surroundings was achieved by dismantling the boundary wall and making the park visible from all sides.

Then the issue of water logging was mitigated through the construction of an aqua trench. This water was then made available to the public as drinking water through filtration processes.

Additionally, there’s a pavilion, a 500 foot walkway, and public plaza where people can relax and socialise.

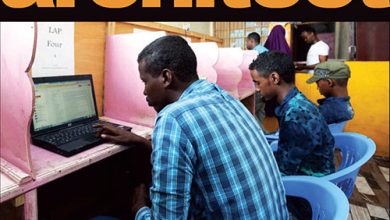

For intellectual pursuits, there’s a library while fitness enthusiasts can utilise the gymnasium. A coffee shop provides a cosy spot for refreshments and a community hall offers a space for gatherings.

In the second stage, the focus shifted to breaking down barriers between the community and park, which in turn fostered a sense of ownership within the community. Locals were encouraged to actively participate in the park’s upkeep and organisation of events by involving the community in the decision-making processes thereby developing mutually beneficial relationships.

Community Participation: A Way Forward

Before construction and renovation could begin, the first course of action was bringing the community together by giving them a role in the project.

Several meetings were conducted with many of the community’s elders, imams (senior figures in the mosque) and youth to collect feedback before holding a public hearing in the park. During the hearing, we presented the plans to the entire community to make sure everybody was on board with the initiative.

The transformed park now offers a diverse range of amenities, catering to various needs and interests within the community. It features a spacious open field for sports, designated cricket practice areas and a dedicated children’s playground. The inclusion of an Eidgah allows for communal prayers and public restrooms ensure convenience for visitors.

This revitalised space serves as a welcoming and family-friendly environment, accommodating a wide array of activities, from sports and leisure, to prayer and education. The enhanced fields and play areas align with the park’s designation as a shishu park, providing safe spaces for children to play and learn about nature, and even harvest fruits like carissa carandas, averrhoa bilimbi and Burmese grapes.

The presence of a dhak tree (Butea monosperma), from which Dhaka’s name originates, adds cultural significance while orchards of kolaboti trees soften the park’s edges and conceal dilapidated walls, blending the park softly with its surroundings.

RESOURCES

Archt. Prof. Rafiq Azam

PHOTOGRAPHY

Shatotto – Architecture for Green Living