FOR WHOM THE CITY TOLLS

SPOTLIGHT

LIVES OF THE CITY’S HIDDEN INHABITANTS THRUST INTO THE FOREFRONT OF RAPID URBANISATION: IN CONVERSATION WITH COLOMBO URBAN LAB

BY Archt. Tarita Nugaduwa and Archt. Dilini Rathnayake

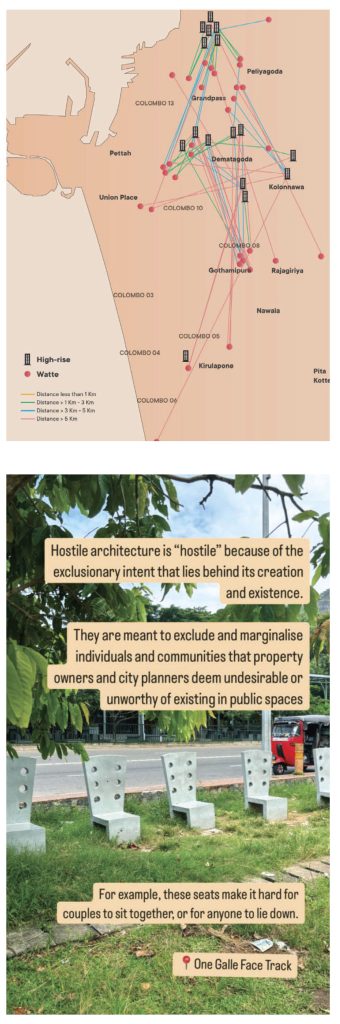

In the bustling heart of Sri Lanka’s capital, where skyscrapers rise and cityscapes are rapidly transformed, a quieter, crucial resistance has been taking shape. At the forefront of this is Colombo Urban Lab (CUL), a research and advocacy collective that has become a vital voice for marginalised urban communities.

Founded and directed by Iromi Perera – a seasoned researcher and activist – CUL works at the intersection of urban development, climate change, human rights and spatial justice, addressing the gaps in policy and planning. Its work focusses on documenting, analysing and challenging the city making and development and how they interact with challenges ranging from economic issues to climate change to support more inclusive urban development through data, dialogue and advocacy.

Perera began her career as a researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), where she first engaged with the impacts of large-scale urban development. During the early stages of the Colombo Urban Regeneration Project (URP) – a government led initiative aimed at transforming the city into a world-class metropolis – she conducted research on its effects on low income communities. Backed by both domestic and international stakeholders, the URP promised to eliminate slums and relocate tens of thousands of low income families into high-rise apartment blocks. Though framed as a modernising effort to improve housing and urban aesthetics, the project quickly became a flashpoint for contention. The issues that Perera and her colleagues at CPA uncovered while conducting research on the outcome of the URP profoundly shaped her commitment to advocating for spatial justice. During the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by the need to carefully examine urban policy and planning through a people centred lens, she went on to establish CUL.

This article explores the work of CUL and Perera, examining how they are reshaping the conversation around urban planning in Sri Lanka, insisting on a more inclusive, just vision for the future of cities.

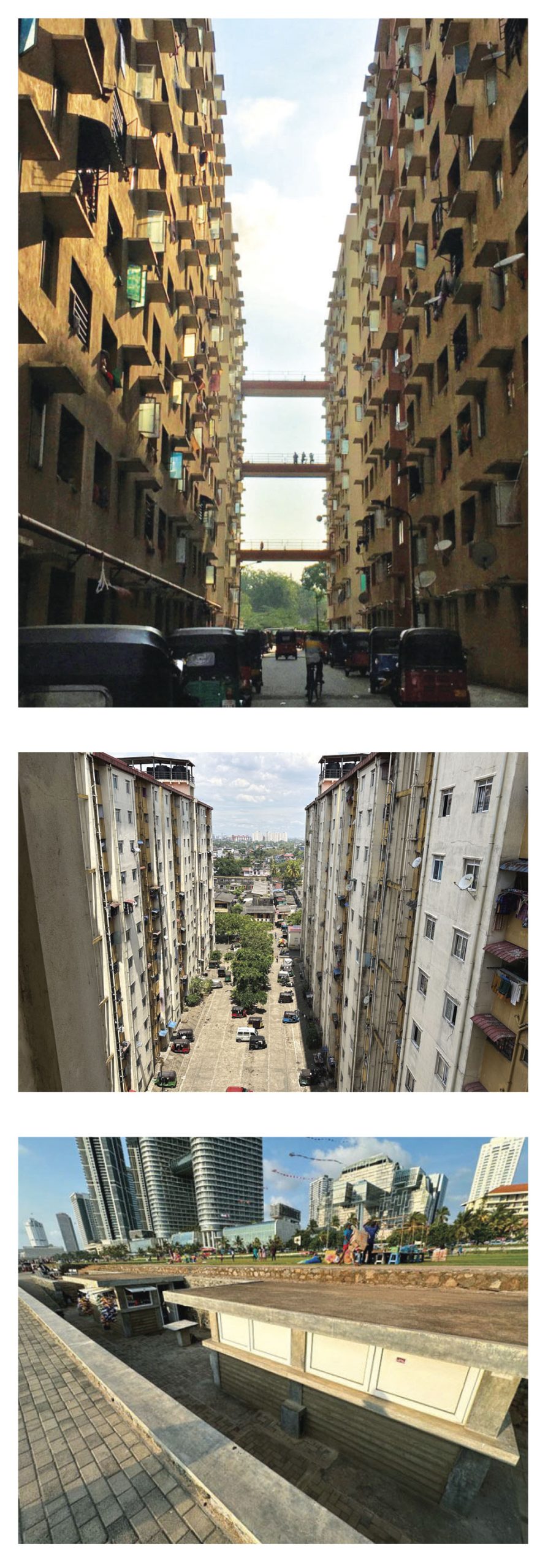

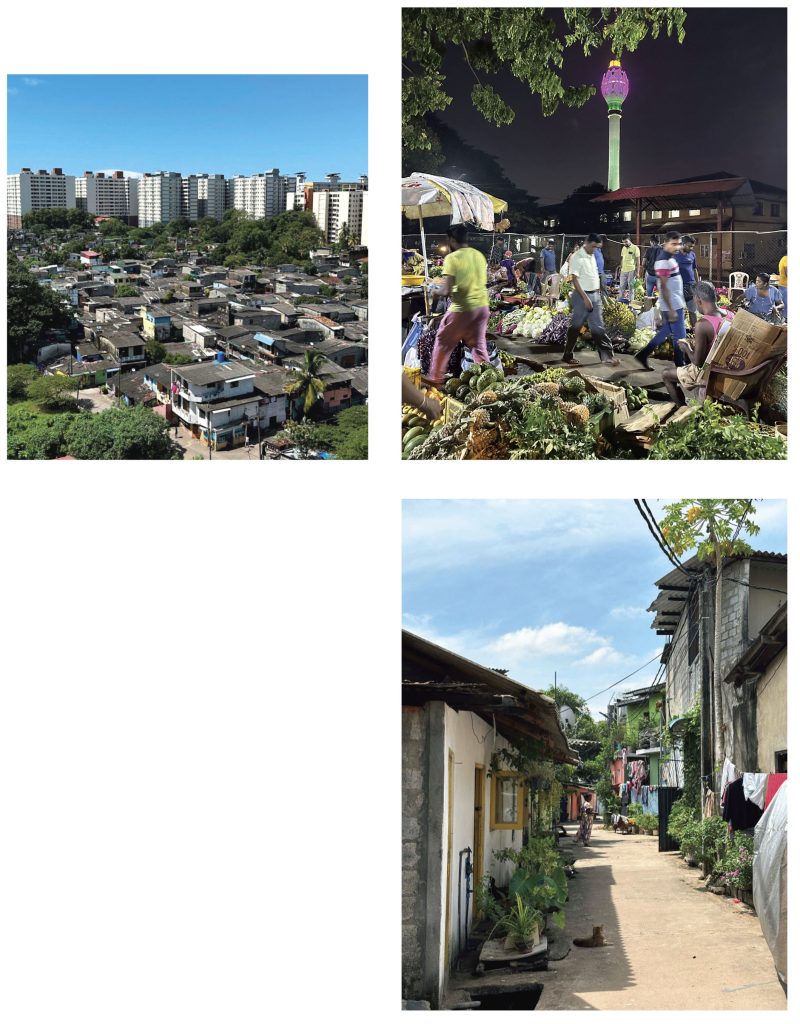

For many of those displaced – despite promises of better housing – the reality of the URP was forced evictions, loss of livelihood, inadequate infrastructure in the new apartment complexes and the breakdown of long established communities. Though they are the most affected, local communities in Sri Lanka have historically been excluded from participating in urban development and planning decisions. Communities living in informal settlements face constant uncertainty, with many living under the threat of eviction or relocation. When development projects come in, communities often lose their homes, jobs and access to basic services. The social networks and support systems that they’ve built over time are also disrupted.

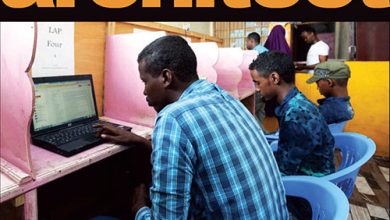

These communities contribute significantly to the city’s economy and culture but their presence is rarely acknowledged in planning processes. Instead, they are seen as obstacles to progress. Though these individuals want to improve their living conditions, they also want to stay where they are – close to work, schools and support systems. Unfortunately, while the city grows, their needs and voices are rarely considered, making it harder for them to stay in the places they’ve called home for generations. Therefore, urban development needs to recognise their rights and include them in decision-making if it is to be truly inclusive.

Over the past few years, CUL has meticulously documented these displacements, highlighting how state led urban development – when devoid of community consultation and social equity – can exacerbate inequality rather than alleviate it. Through rigorous research, grassroots engagement and advocacy, their work offers a critical counter narrative to the glossy promises of urban transformation, and centres instead on the voices of those who are most affected yet least heard.

Perera explains a few of the biggest challenges they face in advocating for marginalised communities within the current urban policy and planning environment: “One big problem we face is that none of the development or master plans really think about people. They think about infrastructure, about buildings, about a particular kind of aesthetic that they consider as world-class but never think about the people who actually inhabit these buildings. And when they do think about people, more often than not, it feels like they’re thinking about tourists and not everyday people. The lack of design consideration given to the end user and the overall dismissive attitude that planners and architects have is a major challenge that we face – especially when we try to communicate the design flaws of low income housing projects.”

“It’s a challenge getting officials to understand that there are other ways in which people can build homes – such as building incrementally and developing them over time – and that taste is subjective and should not be imposed. The issues we face are not just with rules and regulations but also with bridging the class gap and helping officials imagine a way of living that, while unfamiliar to them, works well for the communities they are designing for,” she adds.

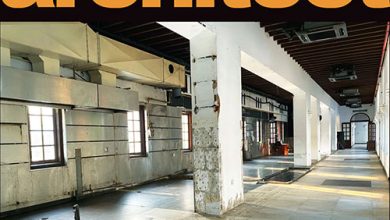

Urban transformation in Colombo is often seen as a sign of development but one that comes at a cost. For many marginalised communities, it means losing their identity and sense of belonging. When people are relocated from their neighbourhoods to high-rise apartment blocks far from their original location, they lose much more than just their homes. They lose access to work, schools and daily support systems. But just as importantly, they lose their way of life. The flats they are given may not suit their needs and the social bonds that held the community together are broken.

In informal settlements, people are accustomed to an open, community centred lifestyle – sharing evening chats outside their homes, gathering near the grocery shops, watching children play in the common spaces and taking part in religious events together. These small, everyday interactions made their communities feel like home. In high-rises, this social fabric is often lost. The design of these buildings doesn’t support the same kind of informal gatherings or collective living.

This change also brings emotional consequences – the loss of identity, memory and culture tied to place. When entire communities are uprooted in the name of city beautification, we ignore the deep ties people have to land, neighbours and the rhythms of daily life. The cost isn’t just physical – it’s social, cultural and psychological. This raises the question: who is the city being modernised for and at what cost? It urges architects and urban designers to think critically on how the language of beautification hides the violence of displacement, and focus on ways to grow while protecting people’s rights, dignity and memory.

Perera highlights the importance of beginning this shift by first acknowledging the role of emerging architects, emphasising the need to integrate values such as social justice and empathy into the architectural school curriculum.

“I feel like a lot of the people we deal with – architects and urban planners – and many of the problems we discuss in terms of public space and social housing stem from a lack of empathy and a reluctance to do something different or really think of the people who will inhabit these spaces. Sometimes I wonder whether it’s because the curriculum doesn’t encourage that kind of critical, empathetic thinking,” she opines.

She also stresses the lack of engagement that architects and urban planners involved in the URP had with the communities they were designing for, noting that some officials held biased or misinformed views on the wants and needs of end users. She remarks: “It would be great if architects and planners extended the same level of consideration given to private clients to public users as well.”

“Another area where the architectural community has failed is in being vocal about the issues that have arisen from substandard public design. I think it’s important for architects and planners to question what is happening in the city – from a design perspective or planning perspective – and be more vocal about it,” she adds.

While it’s easy to be critical of public institutions, Perera shares that her experience has also brought her into contact with public officials who show genuine empathy and care. These are individuals who take the time to listen, recognise that there are deeper, systemic issues at play and try to make a difference – however small it may seem.

She recalls instances where officials – after truly engaging with the communities – went so far as to alter the layout of housing units based on what people needed. “I admire those who go the extra mile to ensure the end user is genuinely satisfied,” she reflects.

She also speaks with a sense of compassion toward many civil servants working within institutions such as the Urban Development Authority (UDA). While these officials are often at the receiving end of public frustration, they too are operating within a system that limits their power. “Many of them are career civil servants caught in the cycles of political change,” Perera explains. “Every few years, a new leadership arrives with a master plan that often disregards that of its predecessors, leaving these officials to implement plans they had no hand in shaping – and to deal with the fallout from the previous ones,” she adds.

She acknowledges that while the system is flawed, many planners, engineers and officials are aware of its shortcomings yet lack the autonomy to initiate change. They become, in effect, the visible face of a much larger issue and absorb criticism for decisions that were never truly theirs.

Yet, amid all this, Perera remains hopeful. She believes that with the right leadership and support – especially from external partners – development can become more just and inclusive. What keeps her going, she says, is the hope that things can and will change. “In our line of work, I think hope is what drives all of us forward. And I do see small changes in people’s mindsets and the way that they approach issues,” she reflects.

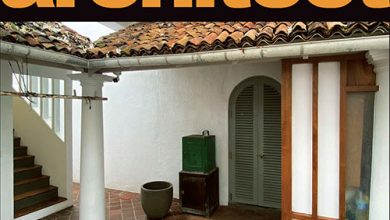

According to Perera, there have been some noticeable improvements in the design of recent public housing projects. She points out that lessons seem to have been learned from earlier developments such as Sirisara Uyana and Methsaru Uyana in Dematagoda, which were criticised for their long, dark corridors that created gloomy, uninviting spaces. In contrast, some of the newer high-rise buildings – particularly those under the second phase of development – feature designs centred around a courtyard. This shift has allowed for greater natural light and ventilation, making the spaces feel more open and liveable.

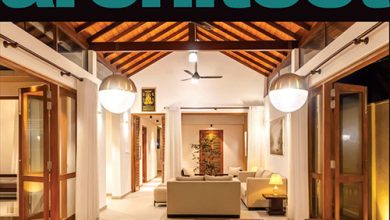

Another example she highlights is a UDA housing project in Slave Island, near Station Passage. This project provided homes for around 120 families who had previously lived in a watte in the area. Perera speaks highly of the engineer in charge, Priyani Navarathna, who made a concerted effort to engage with the community throughout the design process.

“Based on her discussions with them, she changed the layout of the apartment according to what they liked. They were quite happy with the designs offered. The families were even given a choice between three different apartment types,” Perera reveals.

Rare but meaningful instances of participatory design in public housing reflect both the needs and values of the communities involved. When people have the option to choose what best suits their lifestyle, they are more likely to be satisfied with the final outcome – and less likely to rent out the new apartments and move back to their old homes – a common issue today.

In response to the questions, “How might architects engage more ethically and meaningfully with issues of spatial justice and community displacement? And is there a way for architects – individually or collectively – to support the work you do at CUL?”, Perera emphasises that architects can play a vital role, both in advocacy and on the ground, by using their skills to amplify community voices and co-create more than just urban spaces. “There are communities who could implement changes on their own without waiting for authorities to do so. In instances like this, it would be helpful to get input from someone with a background in architecture or planning,” she suggests.

She also mentions that architects can get involved in advocacy – whether by proposing design changes to housing projects or helping communicate alternative options to UDA officials and guiding them towards more imaginative solutions. “It would be so lovely to have young architects willing to sit and talk to communities with us and help us come up with solutions,” she states.

What CUL calls for from the architectural community is simple acts of solidarity and collaboration, grounded in empathy and a willingness to include those who are often left out of the urban design process.

Drawing from her experience in Bombay, Perera shares several encouraging examples of collaboration between architects, students and communities. “Over the years, I’ve come across interesting initiatives at architecture schools such as the Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, where students work on real housing issues in the city. It gives them valuable hands-on learning and helps address critical gaps in public housing,” she shares. Perera also highlights the role of NGOs such as Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA), which work closely with communities and architects to develop blueprints and suggest alternatives to conventional master plans. She recalls meaningful contributions during the drafting of the Delhi master plan, including efforts such as documenting evictions of informal settlements known as bastis.

Sharing her message with emerging architects interested in equity, housing justice and ethical urbanism, she says, “Do not be afraid of words such as justice and rights. You can incorporate those words into your practice, Think about how your work can be accessed by the public at large – whether it’s informal vendors or kids running around after school. It would be nice to think of a world where architecture doesn’t necessarily mean something elite or expensive. You can think of rights and justice as something that’s really embedded in your practice.”

As Colombo continues to evolve into a modern metropolis, the question of for whom the city is built becomes more urgent than ever. The climate crisis also demands that we take issues like heat stress and extreme weather seriously in any planning and development work. The work of CUL, challenges us to rethink developments that often prioritise aesthetics and investment over inclusion and dignity. Their research and advocacy highlight the deep social and emotional costs of displacement, along with the resilience and wisdom embedded in the communities that make up the city’s hidden core.

This is not just a call for better housing or more equitable policy – it’s a call to reimagine the city with, and for, its people. For architects, planners and policymakers, the challenge lies in thinking beyond limits to embrace participatory, community driven designs. It means listening more and assuming less – to recognise that justice and a sense of belonging are also essential to a city’s development.

CUL reminds us that cities encompass more than concrete and infrastructure. They are lived spaces shaped by the people within them. If we are to imagine urban futures that are truly sustainable and inclusive, the voices from the margins must move from the periphery to the centre of the conversation. Only then can our cities become places of dignity, equity and shared belonging.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Colombo Urban Lab

If you are interested in contributing to or volunteering with Colombo Urban Lab, you can contact them at info@colombourbanlab.com