COVER STORY

LMD EXCLUSIVE

POLICY OUTLOOK

Deshamanya Prof. W. D. Lakshman highlights the role of the monetary authority in addressing major policy concerns

Deshamanya Prof. W. D. Lakshman assumed duties as the 15th Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) in December. The veteran economist has previously served as the Vice Chancellor of the University of Colombo and carries the title of Professor Emeritus, which reflects his notable contributions to the field.

A prolific researcher, Lakshman has authored numerous research papers on a wide range of topics including the political economy, economic development in the South Asian region, Japanese investments in South Asia and the socioeconomic impact of structural adjustment policies in Sri Lanka.

At different points in his academic career, he has served as a visiting professor in foreign academic institutions – in the Netherlands, Japan, Yugoslavia and India.

Lakshman has also functioned as a Member of the Presidential Commission on Finance and Banking (1990), Senior Economic Advisor to the Ministry of Finance and Planning (2008-2009), Member of the National Economic Council (2008-10), Chairman of the Presidential Commission on Taxation (2009-2010), Chairman of the Institute of Policy Studies (2010-2015) and Chairman of the Committee of Experts appointed to examine the Sri Lanka-Singapore FTA in 2018.

In this exclusive interview with LMD, he focusses on the state of the economy in Sri Lanka as well as further afield, and provides an overview of the chief monetary policy concerns for the nation. The outcome as it turns out, is a glimpse into the economic philosophy of an expert in the policy domain.

– LMD

Q: What is your take of Sri Lanka’s economy? And what concerns should be addressed going forward?

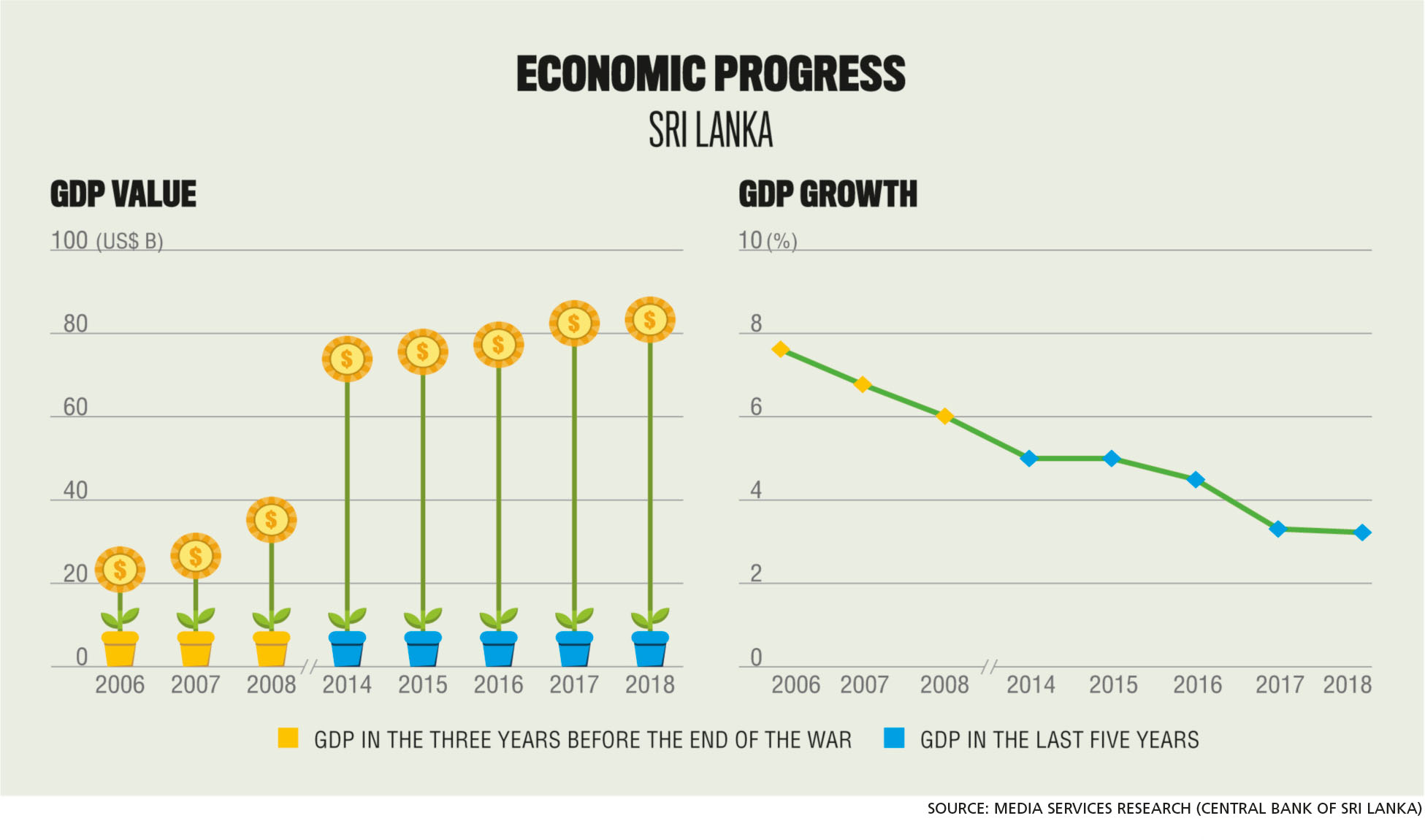

A: Following a period of sluggish growth, the economy seems to be witnessing the prospect of long-term progress due to greater political stability following the presidential election and growing confidence in the business sector.

Between 2015 and 2019, economic growth slowed down to less than three percent. There are different growth projections for 2020. My expectation is that we would witness a growth rate of between four and five percent. This is primarily due to conditions pertaining to business confidence.

Recent tax reforms, as well as changes in the banking sector vis-à-vis loan payment moratoriums for the small and medium sector, have helped in improving business confidence. Slowly but surely, investment will grow.

Maintaining a low interest rate scenario and stable exchange rate are leading concerns.

Deficit financing has traditionally been a feature of Sri Lankan budgetary practice. Action is required on that front as well. At its inception, the present government reduced tax rates substantially, which brought about positive results in terms of business performance and confidence. However, there has been a decline in state revenue but a compensating drop in expenditure is being achieved. Yet, the budgetary management may require close monitoring.

In addition, there is the traditional current account deficit in the balance of payments (BOP). So it is necessary to promote exports while promoting domestic production and to discourage nonessential imports of goods that can be produced locally.

Q: Could you outline your philosophy on currency management – and how would you assess the value of the Sri Lankan Rupee at present?

A: The rupee has depreciated consistently over the last 40 years. The regime of liberalisation taking root from 1977 onwards and the nature of the contemporary global exchange rate regime were behind the depreciation of the rupee to its level today.

Coming down to more recent times, there was substantial rupee depreciation in 2018 followed by a degree of stabilisation since the end of last year.

As for my philosophy, I don’t believe in allowing the rupee to depreciate as it has in the past.

A depreciating rupee may be justified by some economists saying it helps promote exports and discourages imports. Under certain circumstances, this may have been the case in some countries, but not in Sri Lanka where both exports and imports seem to be rather inelastic in demand. The Sri Lankan situation demands a relatively stable rupee maintained by greater stability of the BOP.

Where foreign exchange receipts are concerned, there was a time when exports accounted for as much as 30 percent of GDP. But over time, this share has declined in spite of the rupee depreciation and lip service paid to export growth. There is clearly a need to boost exports through an effective policy framework. Exports, which account for approximately 13 percent of GDP at present, should gradually increase to higher levels.

Meanwhile, imports should be curtailed or policy measures introduced to maintain them at an affordable level.

To this end, different policies have to be adopted without depending entirely on liberalisation as in the past.

Liberalisation may be used in certain instances but it does not engender stable economic conditions. If imports increase rapidly, the government would have to introduce controls. Moreover, if exports are not growing in spite of the incentives provided, the incentive structure needs careful reform and monitoring.

Over recent months, the exchange rate has remained relatively stable, to which end there is a need to maintain foreign official reserves at an acceptable and stable level.

Q: Do you expect inflation to be curbed in the coming months?

A: CBSL presents its objective as maintaining single digit inflation. The Central Bank is doing its part to retain inflation at around a low and stable five percent. Government action to promote production in the real economy and make market processes more efficient also seems to be working towards this objective.

Inflation is the result of many factors, of which only a few are under the control of CBSL. To a large extent, inflationary factors arising from the demand side are under the control of the monetary authority. But there are many aspects affecting inflation that emanate from the supply side that are outside the control of the Central Bank as reflected in the recent experience in food price product inflation.

In addition to CBSL action to maintain inflation at a low level, there are the policy measures introduced by the government. Various production incentives provided by the government help expansion of production for people’s consumption.

Policy measures should be introduced to address numerous problems cropping up at different times. One cannot be dogmatic and say ‘open up trade and everything will be okay.’ In the past, governments seemed to have thought that liberalisation was the solution. Markets can and must also be guided by state action.

Q: Where are interest rates likely to head and what are the underlying sensitivities in this regard?

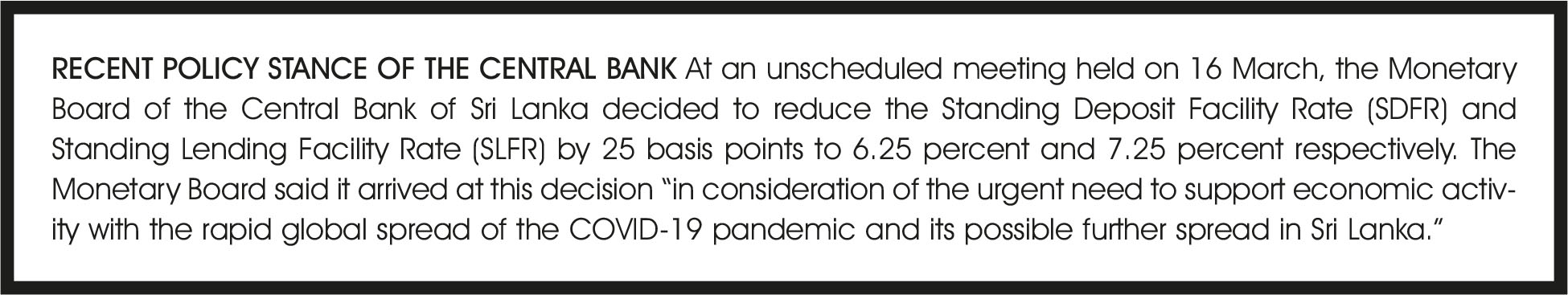

A: Over the last few weeks, there has been a gradual decline in interest rates. This was motivated by the reduction in CBSL policy rates several weeks ago, indicating an accommodative monetary policy stance.

We expect financial institutions to reduce market lending rates further in line with lower policy rates and improving liquidity conditions.

At present, the objective of relevant departments of the Central Bank managing open market operations, public debt and the securities market would be to retain interest rates at a low level so that investment will continue to grow.

Q: How important is the consolidation (i.e. through mergers and acquisitions) of banks and financial services institutions in Sri Lanka? Do you think there’s a need for this?

A: This is a tricky area. Issues in banks and non-bank financial institutions are different. There are concerns particularly about a number of finance companies, many of which are relatively small to have capital adequacy problems.

The Central Bank is conscious of the problems in these companies and effective action will be taken soon to urge them to acquire adequate capital or consolidate; action will be taken to compel them to merge with others. The objective would be to establish a strong financial institution sector.

Consolidation is clearly needed – this could mean individual companies pumping in more capital or merging with others so that capital adequacy can be ensured.

Q: Could you outline your vision for Sri Lanka’s banking system as well as expectations of private sector banks?

A: In the first couple of decades after independence, Sri Lanka’s banking system comprised a few large public and private sector banks, and several foreign banks – perhaps less than 10 banks. After 1977, the banking system was opened up and we witnessed the emergence of many new banks.

There are 26 licensed commercial banks and six licensed specialised banks in operation today. Many of them are small, and two state banks control the bulk of deposits and assets in the system. Foreign and other more powerful but smaller banks control only a fraction of deposits, and primarily cater to corporate customers. There is a need for a policy for banks to expand their reach and activities across the country.

Q: What is your take of Sri Lanka’s investment prospects, and where will the large investments come from?

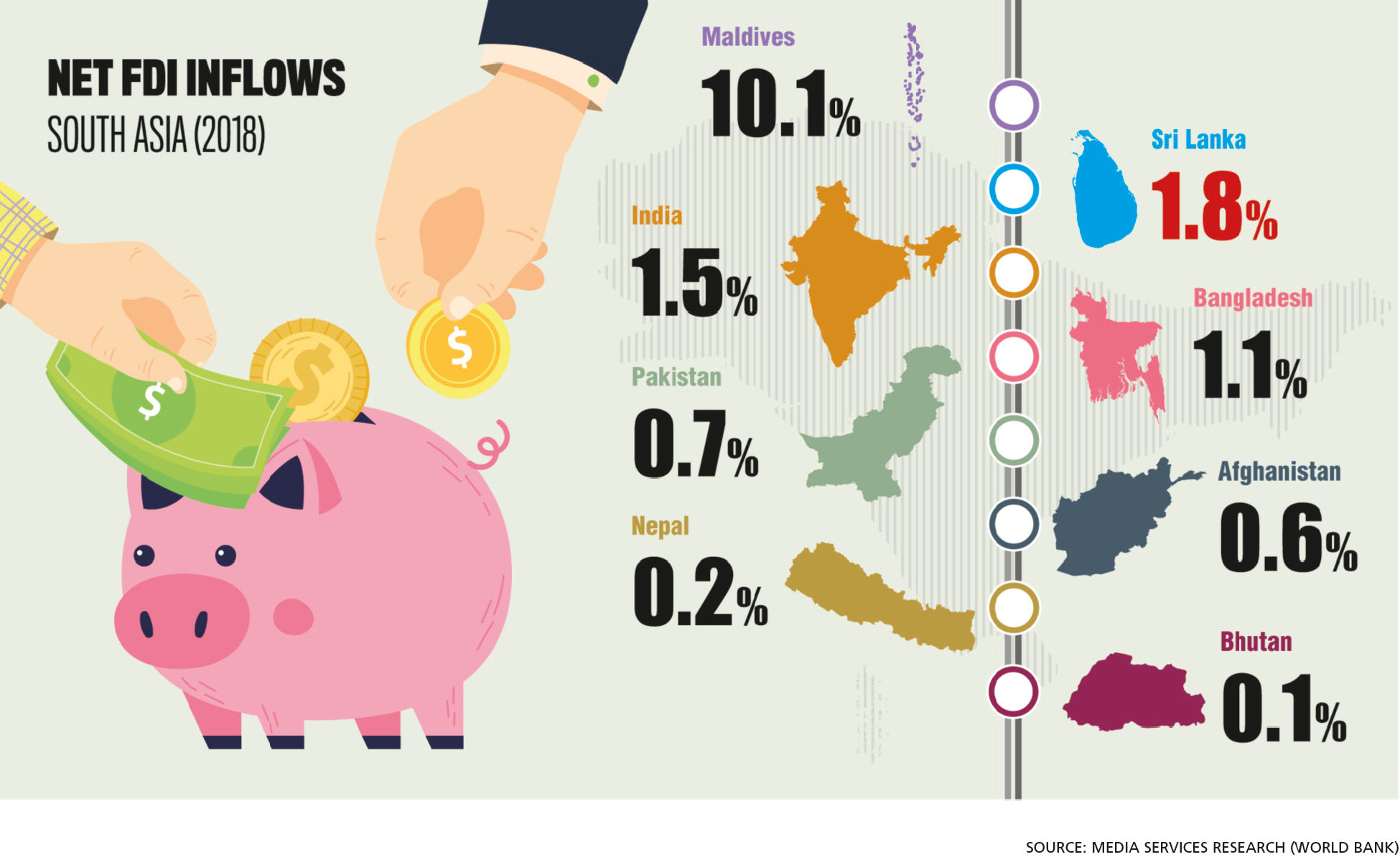

A: I strongly believe that investment prospects are likely to improve and my strongest dependence is on domestic capital, both private and state. Foreign direct investments (FDI) are no doubt important. With the growth of domestic investment, there will also be growth of foreign investment. Focussing on FDI, I do not think it would be restricted to one or two countries.

Depending on the attractiveness of the Colombo International Financial City (CIFC a.k.a. Port City), investments could stem from China in maritime and trade activity, or Singapore, India or anywhere else for that matter.

The sources of investment could be quite diversified.

Q: Is there an ideal strategy to draw in foreign investors and which economic sectors will mainly benefit from it?

A: In the past, Sri Lanka has expected foreign direct investment (FDI) to play a crucial role in economic development. For example, the previous regime (i.e. from 2015 to 2019) had its major focus on FDI. But this has not materialised in reality. My personal belief is that FDI does not have such a critical role to play.

FDI growth in Sri Lanka has been relatively slow and inadequate, compared to the likes of Vietnam and Bangladesh. There is the need for political stability and conducive incentive structures to attract FDI into a country. Likewise, there’s a need for a strong domestic entrepreneur class. Most FDIs take place in the form of joint ventures.

My philosophy of development or investment is that there needs to be a focus on three types of capital: domestic private capital, foreign private capital and state capital. A suitable combination of these – or a ‘coalition’ – is required for a country such as Sri Lanka to take off.

Sri Lanka’s vast state owned enterprise (SOE) sector has not been facilitated to grow commercially generating profits. If these SOEs were managed by a suitably competent and efficient managerial class, Sri Lanka could lay claim to a robust stock of domestic state owned capital to partner the other two forms of capital.

The public enterprise sector as it is now is a drain on government revenue. By making the sector productive and efficient, the losses of the sector can be eliminated, thereby providing resources and revenue to the state while serving the public. At the very least, a large outflow of government revenue could be prevented, making state budgetary management easier.

Q: In your opinion, what are the key sectors in the context of accelerating growth? And is there a need for further stimulus measures to kick-start our economy?

A: There’s a tendency to think that CBSL focusses on financial and monetary matters, while the real production activities and trade are handled by the rest of government. But I believe that the Central Bank has a role to play in promoting real economic activity as well.

In the last several decades, the Sri Lankan economy has moved towards being dominated by the services sector, which contributes to over 56 percent of GDP (around 62% GVA).

Historically, countries that achieved advanced economy status became services dominated only after they reached a high level of income. But in Sri Lanka, the services sector has grown to above 40 percent of the economy even at relatively very low income levels.

Sri Lanka has to strengthen its manufacturing sector and agricultural sectors, which hold many import substitution and export opportunities along with significant progress in agro-industry. The agriculture sector must be modernised and commercialised so that it is attractive to younger individuals.

Additionally, there’s a need to aim for higher value segments in the supply chain.

Most importantly, the agriculture and industry sectors require state guidance, incentives and investment promotion facilities.

Q: How would you describe Sri Lanka’s country risk profile?

A: In the past, there was substantial political risk but this is not the case at present. Global power struggles among superpowers – in our case, particularly among the US, India and China – do affect small nations such as Sri Lanka. We will have to manage our relationships with them with caution to mitigate the risks.

Furthermore, there are risks associated with commodity price fluctuations, as well as those in international exchange rates and interest rates. There are in addition, the implications of the global business cycle. While these risks cannot be avoided completely, the domestic economy would have to be managed with an eye on the question of addressing these.

As for domestic risks, one may point to budget deficits, a major increase in non-concessional external debt and accumulated losses of SOEs. These risks highlight the need for small open economies like Sri Lanka to maintain policy buffers such as international reserves, and adequate space in monetary and fiscal policies. The Central Bank’s risk management department deals with some of these and many other risks affecting the financial sector.

Q: In terms of Sri Lanka’s debt portfolio, how confident are you that Sri Lanka will be able to manage its foreign and short-term debt exposure?

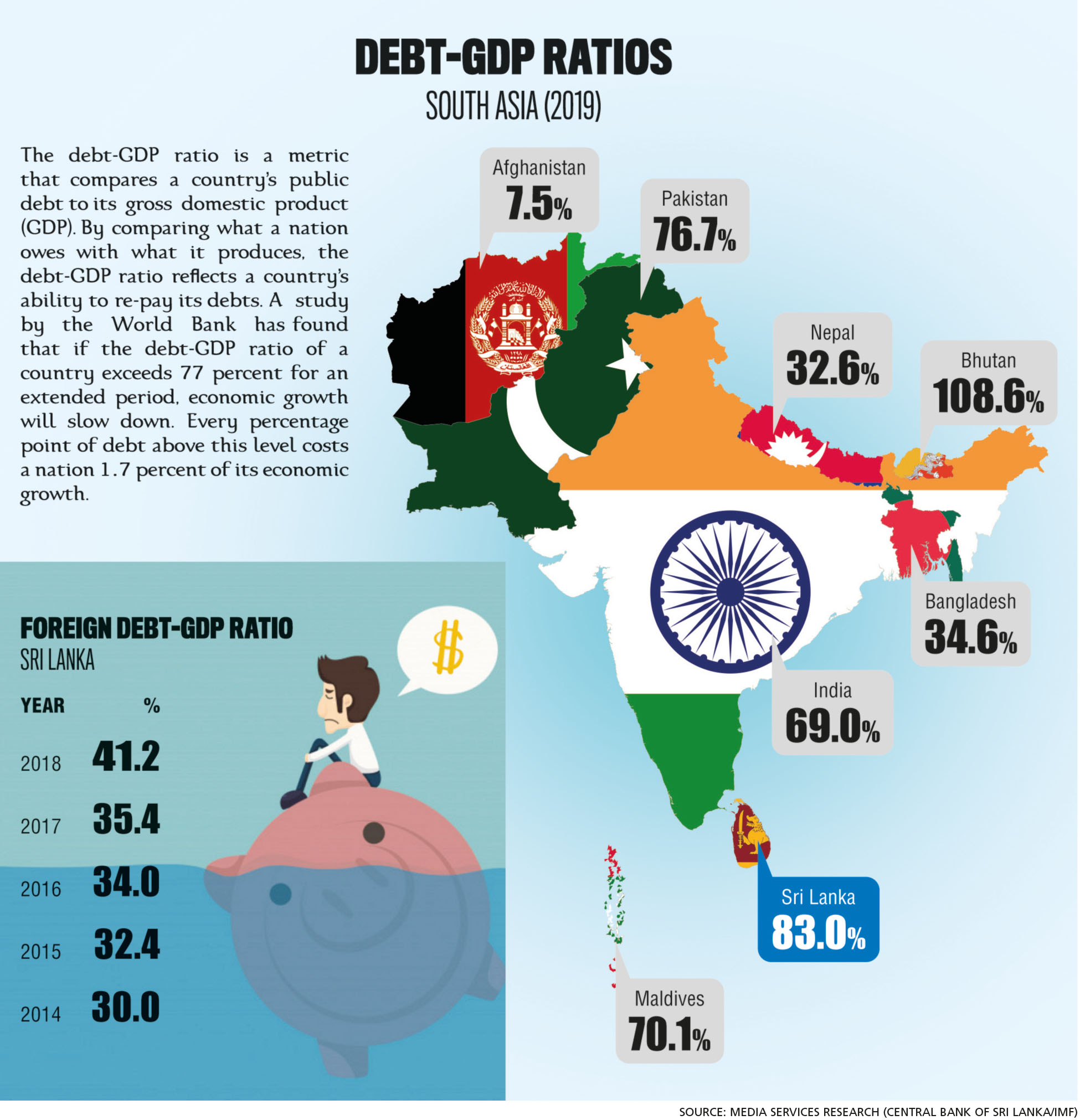

A: Sri Lanka has the reputation of never having defaulted on its debts. All throughout, CBSL was the government agent handling debt. The relevant departments of the Central Bank are confident that the prevailing debt level can be handled effectively without any default risks.

At present, Sri Lanka’s central government debt accounts for approximately 84 percent of GDP. These debt levels have been reduced in spite of the three decades of war and related heavy expenditures.

In the post-conflict era, debt has spiked due to credit taken at market oriented interest rates. Sri Lanka has lost virtually all important sources of concessional lending because of its higher economic standard and the achievement of middle income status. As a result, large volumes of loans had to be taken at interest rates to expand the required investment in the postwar period.

Through prudent public finance policies and careful debt management by CBSL, debt levels can be managed easily when investments begin to produce results, particularly in terms of promoting the country’s exports and other foreign inflows.

The present government has adopted an interim policy of not seeking any loans for new large investment projects whereas those covered by past loans will be completed. This would help ease the debt burden.

Q: What are the chief obstacles that Sri Lanka is likely to face in the near to medium term on the global front? How will the country overcome them, in your opinion?

A: Let me focus only on the coronavirus outbreak and its implications. Certain sectors are already feeling the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. In the Sri Lankan tourism industry for example, Chinese arrivals were significant, accounting for over eight percent of total arrivals in 2019.

The closure of the world’s manufacturing hub has a major impact on the global shipping trade, and will negatively affect Sri Lanka’s ports and shipping sector. This will also impact the export sector in terms of logistics and transport issues.

In addition, China is a key source of Sri Lanka’s intermediate imports and Chinese workers are involved in projects in Sri Lanka. Any downward pressure on China’s growth will also produce adverse impacts on Chinese investments in Sri Lanka.

COVID-19 has spread to South Korea and Italy – two countries with large concentrations of Sri Lankan workers. If the situation becomes as grave as it has been in China, they would have to return to Sri Lanka, thereby impacting overseas remittances. Meanwhile, the drop in oil prices comes out as a positive effect of COVID-19. But this in turn could affect remittance flows from the Middle East.

Evidently, there are positives as well as negatives to being part of a globalised economy so the country has to learn to live with both.

Q: You have said recently that the IMF should not be treated like “an enemy” and that “difficult decisions” will have to be made by our political leaders… Could you elaborate on this?

A: So far, there have not been any concrete steps taken to develop alternative programmes. Most probably, something along similar lines would commence following the parliamentary elections.

An alternative programme must be developed within the framework of government policy. It should represent a joint effort. Sri Lanka has to be proactive and express its opinions to the IMF.

Q: Has there been progress in transforming the public service into being free of bribery and corruption – and what more must be done, in your opinion?

A: Bribery and corruption is a curse affecting Sri Lanka. Regulations and other measures need to be combined with human development efforts from school days on if we are to minimise this scourge if eradication is infeasible.

In the early stages of Sri Lanka’s parliamentary system of governance, there were no major complaints about public sector corruption. Instead, there were instances referred to in public discussion about the high level of honesty among the people in public service, political as well as administrative. But that period is long gone. While nobody seems to know how to reverse this trend, it has to be done.

Q: How does the Central Bank plan to maintain an independent and transparent role in economic development?

A: CBSL was established as an independent institution in the 1950s and is celebrating its 70th anniversary.

There were lapses on the part of Central Bank in the supervision and regulation of the country’s financial sector as was seen a few years ago. Yet, there is no threat to CBSL’s independence, which must be maintained – albeit not as an ivory tower separated from the rest of society. The organisation is meant to achieve objectives in service to the people.

It has expanded considerably since its establishment with some 30 departments handling a diverse set of subject areas. While managing monetary or financial matters to maintain the stability of financial institutions in the country, it has to work in collaboration with the Treasury to achieve a broader set of objectives of shared socioeconomic development.

In my opinion, the position of governor of the CBSL should be offered to this remarkable economist because I believe that his knowledge and experience can lead our country towards a better economic situation. Past appointments to the CBSL have always involved a political hand. So this will finally be a turning point for our country.