COVER STORY

LMD EXCLUSIVE

A MATTER OF PROTECTION

Saliya Pieris stresses the need to strengthen Sri Lanka’s independent institutions and protect the rights of weaker segments in society – and calls on the business community to play a part in this process

Following an election in which he secured more than 5,000 votes, Saliya Pieris was inducted as the 26th President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) for 2021/22 on 27 March. The President’s Counsel practises in the areas of criminal and public law, and fundamental rights in the appellate and original courts.

Following an election in which he secured more than 5,000 votes, Saliya Pieris was inducted as the 26th President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) for 2021/22 on 27 March. The President’s Counsel practises in the areas of criminal and public law, and fundamental rights in the appellate and original courts.

An advocate for strengthening human rights, and a staunch supporter of the rule of law and independence of the judiciary, Pieris previously served as the Deputy President of the BASL – and he was the first Chairman of the Office on Missing Persons and a member of the Human Rights Commission Sri Lanka.

He is also credited with playing a prominent role in the lawyers’ campaign against the impeachment of former Chief Justice Dr. Shirani Bandaranayake.

At the BASL’s annual convocation, Pieris emphasised his commitment to the values of freedom, equality, justice, fundamental human rights and the independence of the judiciary. Additionally, he said his love for Sri Lanka fuelled the belief that the country “must be one that safeguards the rights of its people including the rights of its weaker segments.”

In this exclusive interview with LMD, he sheds light on the challenges the judiciary faces in the prevailing landscape, the need to strengthen the rule of law, and steps that must be taken to address the scourge of bribery and corruption in the country.

– LMD

The business community often looks to its own parochial interests and fails to stand up for the rule of law and democracy. We see business leaders lamenting about the state of the nation in private, complaining about corruption, political interference and influence peddling. However, they refuse or do not have the courage to take public positions on issues affecting society at large

Q: How do you view the state of the judiciary in Sri Lanka at this time – and what are the major threats to its independence, if any?

Q: How do you view the state of the judiciary in Sri Lanka at this time – and what are the major threats to its independence, if any?

A: The last few decades have been a challenging time for the country’s judiciary – especially in respect of its independence.

Since 1978, there have been three attempts to impeach different chief justices – Neville Samarakoon, Sarath N. Silva and Dr. Shirani Bandaranayake, the latter of whom was removed and restored.

At the same time, there’s been some of its proudest moments such as the seven judge decision in the ‘dissolution case.’ The courts have also delivered important judgements in areas of fundamental rights and the environment. However, there have also been missed opportunities in strengthening the judiciary and rights of the people.

As an institution, the judiciary has certainly come under scrutiny more than ever before and also criticism – some valid; some not so valid.

So in the words of Dickens in the Tale of Two Cities, I would say that ‘it was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’

The major threats to its independence come from both outside and within. There have been attempts to interfere with the independence of the judiciary from other organs of the state – both the executive and

legislature.

From the 1970s, the appointment process of judges – especially to the higher judiciary – has been called into question.

While we have had the 17th and 19th Amendments, which imposed some checks on the president’s powers of appointments, they have been removed by the 20th Amendment. The appointment process through the Constitutional Council under the 19th Amendment too should have had greater transparency.

In my view, another threat to its independence comes from the media and public opinion. Courts cannot always do what is popular or desired by sections of the media.

The threat to the independence of the judiciary from within is from individuals who compromise their independence and integrity for different reasons. Each judge has a duty to uphold his or her independence. Chief Justice Samarakoon once said: “No surgeon on Earth can repair a judge’s spine once he’s lost it.”

Q: What do you consider to be the main challenges restricting the administration of justice in Sri Lanka and how can they be addressed?

A: I would identify delays in legal proceedings as the single most challenging restriction impacting the administration of justice. We see both criminal and civil cases taking years or sometimes decades to resolve; I’ve appeared in cases that were instituted before I was born.

As a result of an influx of civil appeals, there are now delays in the apex courts – especially the Supreme Court. Such delays deprive litigants of the fruits of their litigation and erode the confidence people have in the justice system. In respect of cases such as those under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, there are accused who have languished in remand for over a decade.

Another challenge is the archaic laws and procedures that stand in the way of justice being administered. These processes need to be revisited and simplified.

An additional challenge is the resistance to change. When those involved have been amenable to change, we have seen positive results.

I would also like to see the issue of miscarriages of justice – post-conviction – being addressed. In other countries, there are mechanisms to address issues of persons being wrongfully convicted due to this. But we do not have such a mechanism once the regular court process concludes.

There is no one recipe for remedying these ills; what’s most important is leadership to drive change. Proper case management, efficient administration and court automation are essential elements in addressing delays in proceedings. Legal education, both pre and post-qualifying, requires change.

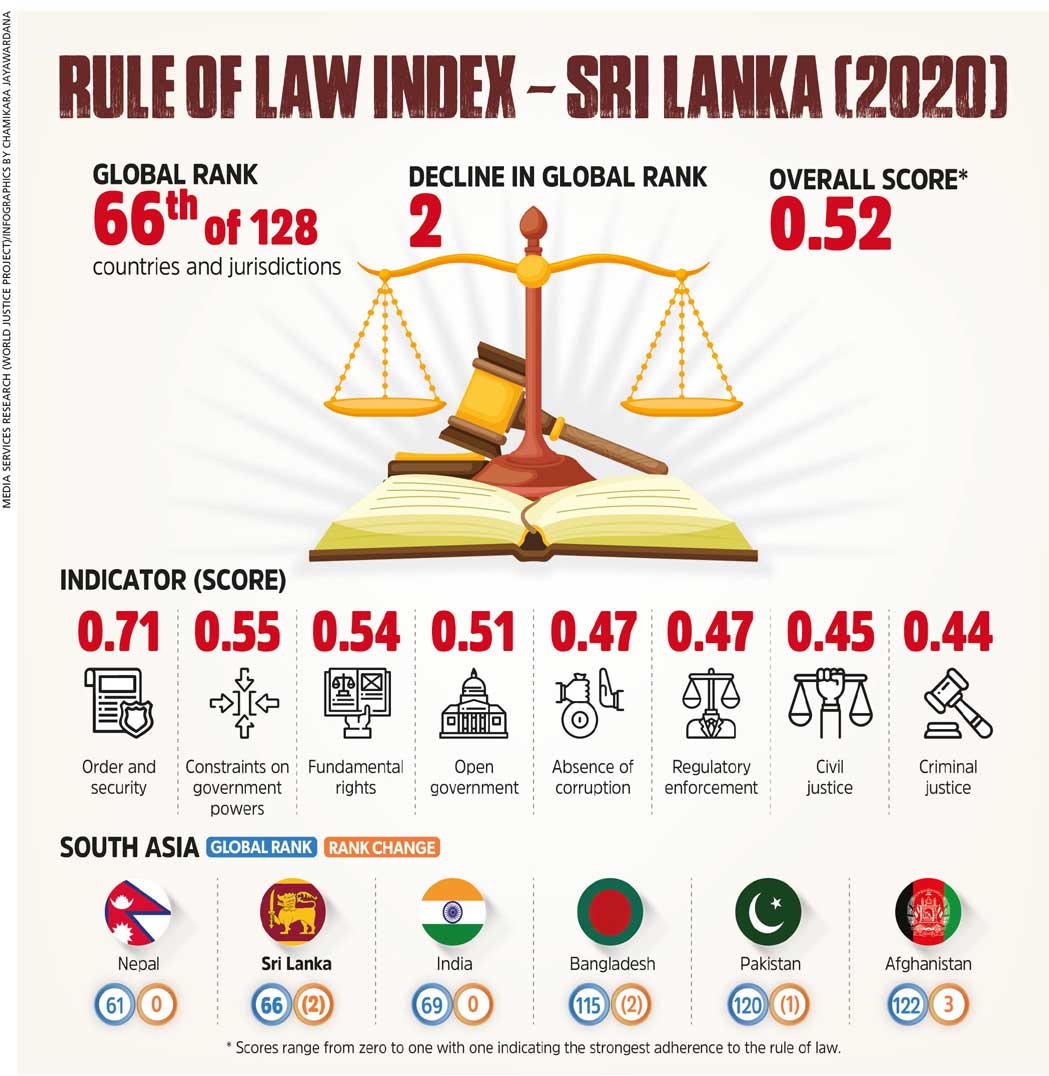

Q: Sri Lanka is ranked 66th of 128 countries and jurisdictions in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2020 with its score of 0.5 remaining largely unchanged since 2015. In your opinion, why hasn’t the country witnessed enough progress in improving the status quo?

A: The Rule of Law Index takes into account eight primary factors – viz. constraints on government powers, the absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice and criminal justice.

In terms of South Asia, Sri Lanka ranks only second to Nepal.

Sadly, the country has not witnessed enough progress in these factors. Addressing corruption, enhancing transparency in government, promoting greater respect for fundamental rights and freedoms are all issues that need to be addressed.

Q: How can the rule of law be strengthened in the country – and what are the barriers to such efforts?

Q: How can the rule of law be strengthened in the country – and what are the barriers to such efforts?

A: The rule of law can be strengthened only if we strengthen our institutions – and preserve and protect their independence. For far too long, we have looked to individuals as saviours, thinking they can deliver. When their tenure ends, many people are disappointed.

In my view, rather than relying on individuals, we must strengthen our institutions – be it parliament, the judiciary or other independent institutions. When institutions are strong, they can resist attacks on the rule of law and their independence.

For instance, in the aftermath of the US presidential election, different institutions resisted then President Donald’s Trump’s efforts to overturn the result despite the pressure they faced. I see the dissolution case as one example where strong institutions can strengthen the rule of law.

The country must address the issues that impact the rule of law. Police brutality, torture, deaths in custody, the issues of disappearances and emblematic cases are matters that must be addressed if we want to strengthen this area in Sri Lanka.

I find the recent custodial deaths to be extremely problematic – they demonstrate impunity on the part of sections of law enforcement authorities.

The barriers to such efforts are when governments deliberately weaken institutions. If they appoint persons who are clearly unsuitable for positions, or on the basis of their political loyalties or other irrelevant considerations, they dilute the independence and effectiveness of these institutions. People within these institutions who perform their duties according to the law need to be protected from partisan attacks on their independence.

If governments attempt to punish officers for doing their job, that will affect the rule of law.

Q: And what role must the business community and civil society play to ensure that the rule of law is upheld?

A: In my view, the business community and civil society need to take principled and public positions on the rule of law.

The business community often looks to its own parochial interests and fails to stand up for the rule of law and democracy. We see business leaders lamenting about the state of the nation in private, complaining about corruption, political interference and influence peddling. However, they refuse or do not have the courage to take public positions on issues affecting society at large.

The business community often looks to its own parochial interests and fails to stand up for the rule of law and democracy. We see business leaders lamenting about the state of the nation in private, complaining about corruption, political interference and influence peddling. However, they refuse or do not have the courage to take public positions on issues affecting society at large.

This is the same with many professional organisations too. If it makes its voice heard, the business community could have enormous influence over how a government acts.

After all, the rule of law encompasses everything and if you fail to take a principled position, sooner or later your business or profession – and the country and its people as a whole – will suffer.

Q: How would you rate the reputation of the nation’s executive branch in upholding the rule of law, supporting the judiciary and respecting human rights in recent years?

A: Its reputation over time has not been great. These days, the rule of law includes respect for fundamental human freedoms. Without fundamental rights, there can be no rule of law.

With respect to supporting the judiciary by way of funding or infrastructure, there has been support from the executive branch. However, what’s most important is for it to uphold the values of the judiciary’s independence and the separation of powers.

There has to be respect for what the constitution has termed the ‘intangible heritage of our people’ – i.e. freedom, equality, justice, fundamental human rights and the independence of the judiciary.

Q: Despite the lack of noteworthy progress in developing the rule of law, Sri Lanka was highlighted among countries that recorded the most improvement in their levels of human freedom between 2008 and 2018 in the Human Freedom Index. What is your take of this assessment?

Q: Despite the lack of noteworthy progress in developing the rule of law, Sri Lanka was highlighted among countries that recorded the most improvement in their levels of human freedom between 2008 and 2018 in the Human Freedom Index. What is your take of this assessment?

A: Fortunately for Sri Lanka, I believe that there is an underlying need for human freedom and democracy despite everything. Our people have pushed back against attempts to erode their freedom. In the face of setbacks, our people still value our freedom and democracy.

This is why democratic change is still possible in Sri Lanka. We have as a nation demonstrated resilience when it comes to democracy and freedom. This may be the reason that – despite all that has happened over four decades – we like to think of our country as being free and democratic.

Q: How would you explain the ongoing permeation of corruption at high levels in this country, despite the existence of numerous watchdogs?

A: In my opinion, our watchdogs have failed. For years, we’ve addressed bribery and corruption at lower levels but failed to address it at higher levels. If you look at many criminal indictments, they relate to ordinary and mundane cases of bribery.

Perhaps it also has to do with our investigation methods. Some of these cases of corruption cannot be investigated by ordinary police officers but must be looked into by persons possessing other skills such as accountancy, forensic auditing and so on.

Q: And how can the business community play its part in stemming the cancer of corruption – would you agree that the golden rule should be to resist the temptation of giving in to this menace in the interest of securing business? If so, what is your message to corporates?

A: In my view, the business community does not sufficiently resist bribery and corruption – it is an accomplice at many levels. It is time this community insists that peers conform to international norms against bribery and corruption.

A: In my view, the business community does not sufficiently resist bribery and corruption – it is an accomplice at many levels. It is time this community insists that peers conform to international norms against bribery and corruption.

We need to change our laws so that those in the private sector who aid and instigate bribery and corruption are charged and punished – similar to what has taken place in South Korea, which dealt with the officials of top corporates.

Q: Earlier this year, you stated that “it is by strengthening institutions and the rule of law, and the rights of the people, that this country can achieve its full potential.” Could you elaborate on this?

A: I have already addressed these issues. The rule of law, strong and independent institutions, and accepting and acknowledging the need to protect the fundamental rights of citizens are important for the development of any country.

No country can really grow unless its institutions are strong and unless there is the rule of law.

There must be a culture that protects the rights of the people of the country. Weak institutions, a lack of respect for the rule of law and rights of people are a recipe for a failed state.

Q: What is your opinion of Sri Lanka’s withdrawal from the co-sponsorship of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) Resolution 30/1 of 2015 in February 2020?

A: The reality is that Resolution 30/1 did not find favour among the majority of the community. If it is to be sustainable, any attempt at dealing with the past must have the support of the majority. Sri Lanka’s withdrawal from the co-sponsorship of the resolution reflects this reality.

Q: And how do you view the UNHRC’s recent mandate to collect and preserve information and evidence of crimes related to the 26 year civil war? What impact could this have on Sri Lanka’s standing on the international stage?

A: Without acknowledging the past and confronting the demons of the past, it will be difficult for us as a country to move on. Some things cannot be wished away.

In my view, strong and independent domestic institutions, which are supported and strengthened by the state, could address many of these concerns and would improve Sri Lanka’s standing on the international stage.

Q: The Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) filed a fundamental rights petition challenging the constitutionality of the Inland Revenue Amendment – the bill proposed to amend the Inland Revenue Act No. 24 of 2017. How can this undermine the rule of law?

A: The bill contained a clause criminalising an opinion provided by a practitioner and the BASL took the view that this was unsatisfactory. Our profession is very much based on the arguments relating to interpretation of the law and we found that an attempt to criminalise providing an opinion to be problematic because it stifles freedom of expression and thought.

This is why we challenged the bill and ultimately, the attorney general agreed to amend it. The final version addressed our concerns in that it had dropped this particular clause.

Q: Additionally, the BASL has challenged the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill. Could you shed light on how this bill could impact the administration of justice in the country?

A: The BASL appointed a committee comprising several respected President’s Counsels and senior lawyers who submitted a comprehensive report. We note that the subject matter of this proposed bill is of national importance, and can carry tremendous and significant economic benefits to the country.

However, it was our view that given its importance, there’s a lack of consultative process and transparency, and insufficient time granted to stakeholders to examine the bill and its effects in detail, considering its long-term impact on the country.

We were also concerned that some of the bill’s provisions took away the jurisdiction of the regular courts within the Port City (a.k.a. Colombo International Financial City or CIFC) zone.

– Compiled by Lourdes Abeyeratne

Leave a comment