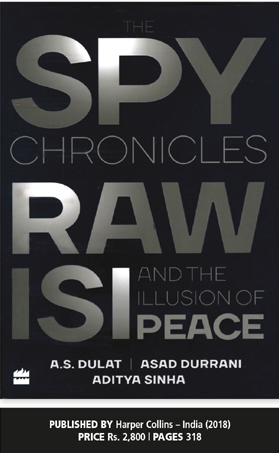

BOOKRACK

Here’s an incredible book authored by two former spies – A. S. Dulat of India’s RAW and Asad Durrani of Pakistan’s ISI with attendant analysis by journalist Aditya Sinha. The Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) is the foreign intelligence agency of India. It’s a well-known name in Sri Lanka because of the role the agency played in training LTTE cadres and maintaining relations with other militant groups.

By Vijitha Yapa

Evidently, former Indian PM Rajiv Gandhi was fascinated by RAW. Dulat claims that Gandhi “relied too much on the agency” and was believed to have met with its agents at 10.30 p.m. every night.

The authors also claim that current National Security Advisor Ajit Doval who was also involved with RAW had been instrumental in persuading Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to permit President Maithripala Sirisena to contest the presidential election in 2015 as the common candidate.

Apparently, Doval was also responsible for convincing Sirisena to move out of the SLFP. All this was because the Indians were unhappy with then president Mahinda Rajapaksa and his leniency towards China.

Unfortunately, the book does not examine RAW’s activities in Sri Lanka. Instead, it concentrates more on India’s and Pakistan’s activities in Kashmir, and formulation of policy. But the views expressed provide insights into the attitudes of the two governments.

Durrani avers that India is a strictly status quo power and improving relations with Pakistan, even if this is not limited to Kashmir, calls for compromise. Since peace requires compromise on certain policies, it’s possibly why the price of peace is at times higher than that of conflict.

He also contends that when unrest begins, the state’s first reaction is to crackdown on protesters. There is a fear that any delay could exacerbate the spread of violence. The first response is a military one and the situation is contained regardless of public opinion. The parties should then be willing to talk and address grievances.

Once an incident is contained, the reaction is that there’s no need for anything more. This is why Durrani feels there will be no meaningful talks on Kashmir between India and Pakistan in the foreseeable future.

Isn’t this happening in Sri Lanka too?

Virtually every day, there are protests highlighting various grievances. If the protesters get close to parliament or presidential offices, the police respond with tear gas and water cannon.

But are the grievances addressed?

The government’s attitude is that since there is freedom to demonstrate now unlike during the previous regime, that alone is sufficient and no further intervention is required.

Dulat asks what the basic problem between India and Pakistan is. The Pakistani High Commissioner says that in Chandigarh, the trouble between India and Pakistan is based on misunderstanding. He then responds with a knockout punch: “What is the misunderstanding when there is no understanding?”

With governments and personalities changing in both Pakistan and India, the continuation of any feasible dialogue doesn’t seem possible. When Dulat talks about proxies being used by Pakistan, he has no answer when Durrani asks about the Indian creation of ‘Mukti Bahini’ in Bangladesh (then known as East Pakistan) during the War of Liberation in 1971.

Durrani says that the one thing common to both countries is the media war and adds that RAW financed an Indian TV station to the tune of US$ 25 million so that it would work for the agency.

Revelations that the Pakistanis cooperated with the US in finding Osama Bin Laden and let the Americans take credit for the capture has led to controversy in Pakistan. Referring to the arrest in 2016 of former Indian naval officer Kulbhushan Jadhav on charges of espionage, Dulat says: “If this was a RAW operation and he was a RAW spy, then it’s a pretty sloppy operation.”

Both Dulat and Durrani feel that a two-year term is not sufficient to head an intelligence agency; they point out that in Israel, the term is six years. Durrani also has strong views on the CIA, which he describes as a great organisation but a third-rate intelligence agency. The authors believe that their respective agencies are burdened with the analysis of intelligence in addition to its collection.

There is banter too. Upon Durrani’s claim that ISI works on a shoestring budget, Dulat replies that RAW has no budget because it isn’t funded by the CIA.

The book provides plenty of insight into the policies of both governments. But it’s a pity that the editing is poor, and dialogue in Hindi and Urdu is not translated, leaving foreigners in the dark about what is being said.