Sri Lanka’s aragalaya was historic. Hundreds of thousands of people thronged the streets of Colombo, camped out for months and surrounded the presidential secretariat – and finally, President’s House – during the protests.

Sri Lanka’s aragalaya was historic. Hundreds of thousands of people thronged the streets of Colombo, camped out for months and surrounded the presidential secretariat – and finally, President’s House – during the protests.

Goons who were enabled by Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) parliamentarians attacked aragalaya protesters on Galle Face Green on 9 July last year. This resulted in a furious backlash by the public and the buses that transported SLPP supporters to a rally at Temple Trees were pushed into the Beira Lake while violence erupted on the streets.

Those who initially led the aragalaya were a disciplined group; but unfortunately, too many spurious leaders entered the process and the once organic protest movement dispersed in many directions.

Fortunately, then president Gotabaya Rajapaksa didn’t order the military to shoot protestors or use violence against the masses who participated in the aragalaya.

One reason for Rajapaksa’s election victory in 2019 may have been the expectation that he would provide tough presidential leadership as he did previously when he served as the secretary of defence, managing the military’s subsequent victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

But he turned out to be a political disaster as he was misled by aides, friends and colleagues.

The leadership that succeeded Rajapaksa wasn’t as tolerant of the aragalaya protesters however, and even arrested some of its leaders.

Sri Lankans wanted system change; but instead, emerging trends show that those in power view ‘system change’ as an opportunity to take away the rights of the people. Democracy is now at stake due to the actions of those in power. And the threat to the democratic rights of people to elect their own representatives is now evident.

Against this backdrop, the decision by the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS) to produce a monumental work, which covers not only the aragalaya and its aftermath but also analyses what has gone wrong in Sri Lanka, is admirable.

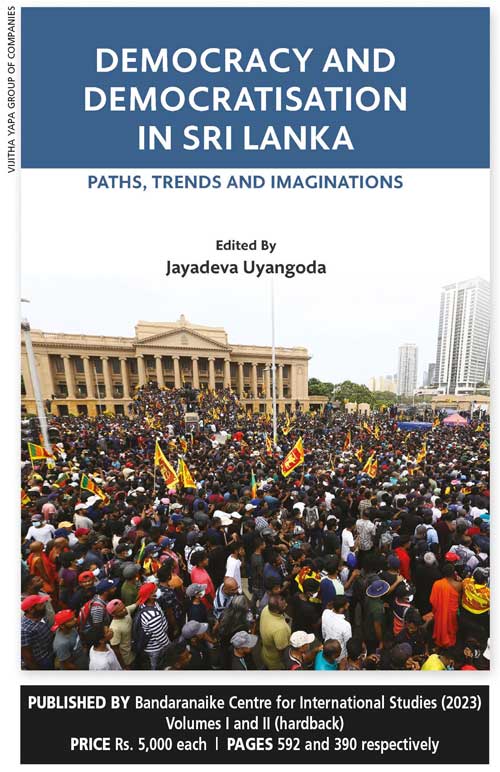

The covers of the two volumes carry images of the presidential secretariat being surrounded by protesters. At a time when news of what transpired during the aragalaya was confined mainly to mainstream and social media, BCIS’ initiative to produce a publication of this magnitude is a milestone for the organisation.

‘Democracy and Democratisation in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and Imaginations’ has been edited by political scientist and constitutional expert Prof. Jayadeva Uyangoda. He has chosen about 20 writers, many of whom are professors in their respective fields, to compile an unprecedented publication.

It is an indication of what an institution such as the BCIS should be doing. Confining its activities to merely teaching and educating future generations in classrooms isn’t sufficient.

This publication is a challenge not only to institutions involved in education but also Sri Lanka’s universities, which need to take the initiative to produce books of quality as essential reading for those who want to see changes to the direction the country takes.

With eminent personalities delving into what Sri Lanka has undergone over the past 75 years, it isn’t possible in this short review to spotlight all views.

The ideas expressed by Prof. Gamini Keerawella on democratic backsliding in Sri Lanka are worth studying.

Prof. Nira Wickramasinghe’s article titled Justice and Redress, and the colonial practice of allowing petitions by the people highlighting injustices to be sent to the rulers, is an interesting read. Does anyone in power even bother to peruse such petitions today?

A piece on working people’s politics and rethinking democracy in Sri Lanka by Devaka Gunawardena and Ahilan Kadirgamar offers valuable insights into what needs to be done in Sri Lanka to protect rights.

And Dr. Farzana Haniffa’s essay on majoritarian democracies and minoritisation issues, and the making of Muslim and Tamil citizens in post-independence Sri Lanka, discusses the crisis of minorities who are wondering where they belong and what their future is in Sri Lanka – where generations of their people have been living.

Uyangoda sums up the purpose of these two volumes: “This work joins the contemporary global effort for producing a dissident body of knowledge on democracy by highlighting the social role of the people, the demos.”

His plea seeks to acknowledge the role of social struggles to strengthen democracy through the recovery of freedom, rights and justice in the context of the unjust exercise of political power.