BOOKRACK

By Vijitha Yapa

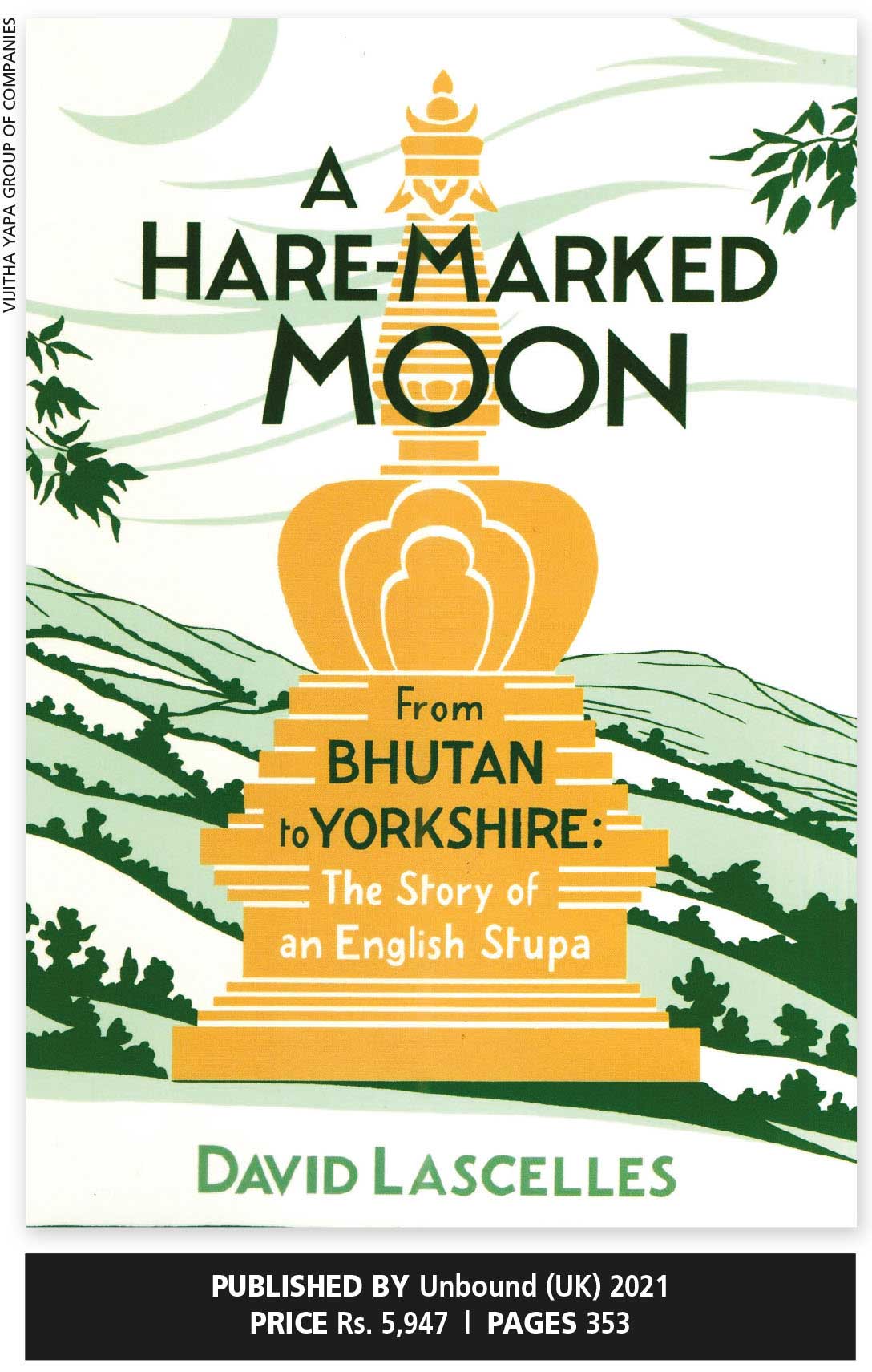

The title may be strange to Western readers but in the East, this refers to the Sasa Jataka story, which is 316th in the list of 550 Jataka tales. Buddhist parents in Sri Lanka show their children a figure on the moon and claim it is that of a rabbit that was willing to sacrifice its life so that a hungry Brahmin could have a meal.

In fact, the hungry Brahmin was the god Śakra and he was so moved by the rabbit’s gesture that he etched an image of it on the moon. It’s also believed that the rabbit was Lord Buddha in a previous life… therefore, perhaps this title: A Hare Marked Moon.

This is a unique true story of David Lascelles, the 8th Earl of Harewood, and his 250-year-old family home in Yorkshire. He acknowledges that Harewood “was built with money made as a direct consequence of the slave trade” and that his ancestors owned enslaved people.

This is a unique true story of David Lascelles, the 8th Earl of Harewood, and his 250-year-old family home in Yorkshire. He acknowledges that Harewood “was built with money made as a direct consequence of the slave trade” and that his ancestors owned enslaved people.

A drawing made of a Japanese pagoda when he was only 10 years old and while travelling with his parents is evidence that from a young age, Lascelles was interested in pagodas, which are the Japanese equivalent of stupas.

In 1976, Lascelles visited Dharamsala, which is the capital of Tibetans in exile. He was fascinated by all things to do with Tibet such as muttered mantras and spun prayer wheels while devotees circumambulated a stupa in the main square.

He also went to Boudhanath (Boudha) in the Kathmandu Valley and walked with those who ambled round the Boudha (Great Stupa). Although Lascelles didn’t know much about Buddhism, he mused: “It seemed such a simple and non-doctrinaire way of engaging with your faith – matter of fact, relaxed, totally accessible and open to everyone.”

The stupas fascinated him and he decided to build one on his compound in Harewood. Lascelles explained to his staff what a stupa symbolised, and that it points upward from samsara to a release from the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

A question arose whether planning permission was necessary. Since it was a monument and not a building in which people lived, he decided to go ahead with it. If objections were raised, he would apologise and apply for permission retrospectively. Were the planners really going to make him demolish a religious monument?

The search for someone to help him build it led Lascelles to Bhutan. An extraordinarily direct and almost physical bond that the Bhutanese seemed to share with their faith fascinated him. And the simple structure of stupas in Bhutan made him feel that one built by Bhutanese was what he’d like in Harewood.

Obtaining visas for them to visit the UK was another issue. Date of birth? Loma Sonam, who was heading the team, replied: “Wood monkey year.” What day? The author discovered that many Bhutanese shared a birthday on their passports – 1 January!

The Bhutanese didn’t know about graphs or measurements by Western standards and that issue needed resolution too. Also interesting from a Sri Lankan point of view is that Bhutanese believe in auspicious times (nekath) and vastu shashtra (architectural science) too, as well as conducting poojas before work.

Though Buddhists believe the creation of a stupa earns one great merit, it was merely an instinctive reaction to Lascelles.

He describes in detail a vision while meditating near the stupa. Lascelles says it was bathed in a bright light – not from an external source but radiating from within. It began to pulse before resolving into rays. Then beams of light streamed out, vibrant with hieroglyphics, which he took to be mantras.

Lascelles recorded this in his diary and reveals it for the first time in this book. Usually, such visions are recorded in other religions; and it is indeed amazing to note a Westerner, who is not a Buddhist, having such an experience.

He decided to visit the eight prominent places of Buddhist worship to discover the origin of the stupas. The author saw no wrong in doing so after he built his stupa – much like having his honeymoon in Bali before he got married!

Interesting facts emerge about how the British thought remains of serpentine symbols and bo trees meant that ancient people were tree or snake worshippers!

For some inexplicable reason, he ignores Sri Lanka and Buddhism here – except to say that King Ashoka sent his daughter Sanghamitta to the island with a sapling from the sacred bo tree. There’s no mention of Arahat Mahinda and how his sermon changed the history of the island. Sri Lanka or Ceylon doesn’t figure even in the index.

Having read the book, a question remains as to whether the author is a Buddhist. There is no answer… because it seems that even he doesn’t know.