BLACK MONEY

THE DAUGHTER OF GREED

Rajika Jayatilake notes that countries are averting financial fraud by banning high-value paper money

‘A lamp does not speak. It introduces itself through its light.’ Another dimension to this is the metaphorical lamp of honesty shining its light and exposing those indulging in financial deceit. Such exposure is society’s responsibility and as Albert Einstein said: “The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

With the root of all evil being attributed to the love of money, it is difficult to prevent financial crimes from taking place when cash is still a global favourite in transactions. According to the Global Findex database of the World Bank, two billion adults still do not have bank accounts.

Nevertheless, a recent study at the Harvard Kennedy School by Peter Sands (the former CEO of Standard Chartered Bank in the UK) asserts that “high-value notes play little in the functioning of the legitimate economy, yet a crucial role in the underground economy.”

He states that criminals are able to shift more than US$ 2 trillion around the world annually. And this type of illicit cash transfers take place because high-denomination bills are in circulation. Moreover, as it is the responsibility of governments to print money, nations appear to have lost control of their cash supply with unwarranted advantages accruing to criminals and tax evaders across the world.

The seriousness of the issue of large bills was first realised in the West but is evident in the East as well today. And developing countries are being galvanised into action.

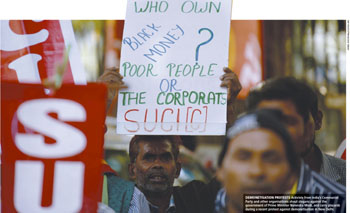

India is the most recent to crack down on the black economy of criminals and tax evaders. Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announced that India’s two largest currency notes – 500 and 1,000-rupee bills that are worth around US$ 7.50 and 15 dollars respectively – are no longer valid for everyday cash transactions. They can only be deposited in banks and exchanged for newly printed notes.

This decision by the Indian authorities comes hot on the heels of Modi’s recent tax amnesty to those hoarding undeclared cash. The tax amnesty was a strategy in an anti-corruption drive that aimed to bring into the open undeclared hoarded cash and stop illicit funds worth billions of rupees from flowing overseas.

The Indian government received over US$ 10 billion through this process and Modi noted: “Black money and corruption are the biggest obstacles to eradicating poverty.”

Meanwhile, South Korea recently initiated TPAY – a digital transactions system – as a step towards eliminating financial crime and crushing corruption. Within two weeks of its launch, TPAY attracted 100,000 subscribers. South Korea plans to rid its economy of paper money by 2020.

In July 2014, Singapore ceased issuing 10,000-Singaporean Dollar bills (about US$ 8,000) to prevent further money laundering, following complaints that it was the preferred currency for bribery in Indonesia.

According to the Standard Catalogue of World Paper Money, the Singaporean Dollar 10,000 note was “one of the world’s most valuable banknotes in circulation along with the 1,000-Swiss Franc note (US$ 1,120), the Singaporean Dollar 1,000 note and the 500-euro note.”

Last May, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank announced that it had decided to “permanently stop producing 500-euro banknotes and exclude it from the Europa series, taking into account concerns that this banknote could facilitate illicit activities.”

In 2010, Britain’s Serious Organised Crime Agency reported that 90 percent of 500-euro bills sold by UK exchange bureaus ended up in the possession of organised criminals. Yet, even with the 500-euro note being taken out of circulation, Switzerland refuses to take its Swiss Franc 1,000 note out of circulation, which is described as ‘the world’s most valuable single-denomination note.’

In the US, Harvard professor and former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, in an op-ed titled ‘It’s Time to Kill the $100 Bill’ that was published in The Washington Post, recommends eliminating the US$ 100 bill.

He stresses that the pursuit of paper money is only beginning.

On another continent, financial analysts at the Swiss global financial services company UBS AG are urging Australia to follow India’s lead and eliminate its high-value paper money. Analysts say that “removing large denomination notes in Australia would be good for the economy and the banks.”

Globally, high-denomination notes are being targeted for termination because they’re a boon to financial criminals. This is because bank notes pave the way for high-value transactions to take place without being detected. While cash is popular because of its anonymity, portability and liquidity, financial criminals will have to find more expensive ways to handle and shift money very soon. Nevertheless, whatever method they choose, the chances of being caught are greater.

Furthermore, with technological innovation leading to more convenient ways of handling financial transactions, it is likely that countries will be printing less money in time to come. And this will narrow the road to fraud and greed… to some extent at least.

After all, as British author Jonathan Gash said: “Fraud is the daughter of greed.”