LMDtv 1

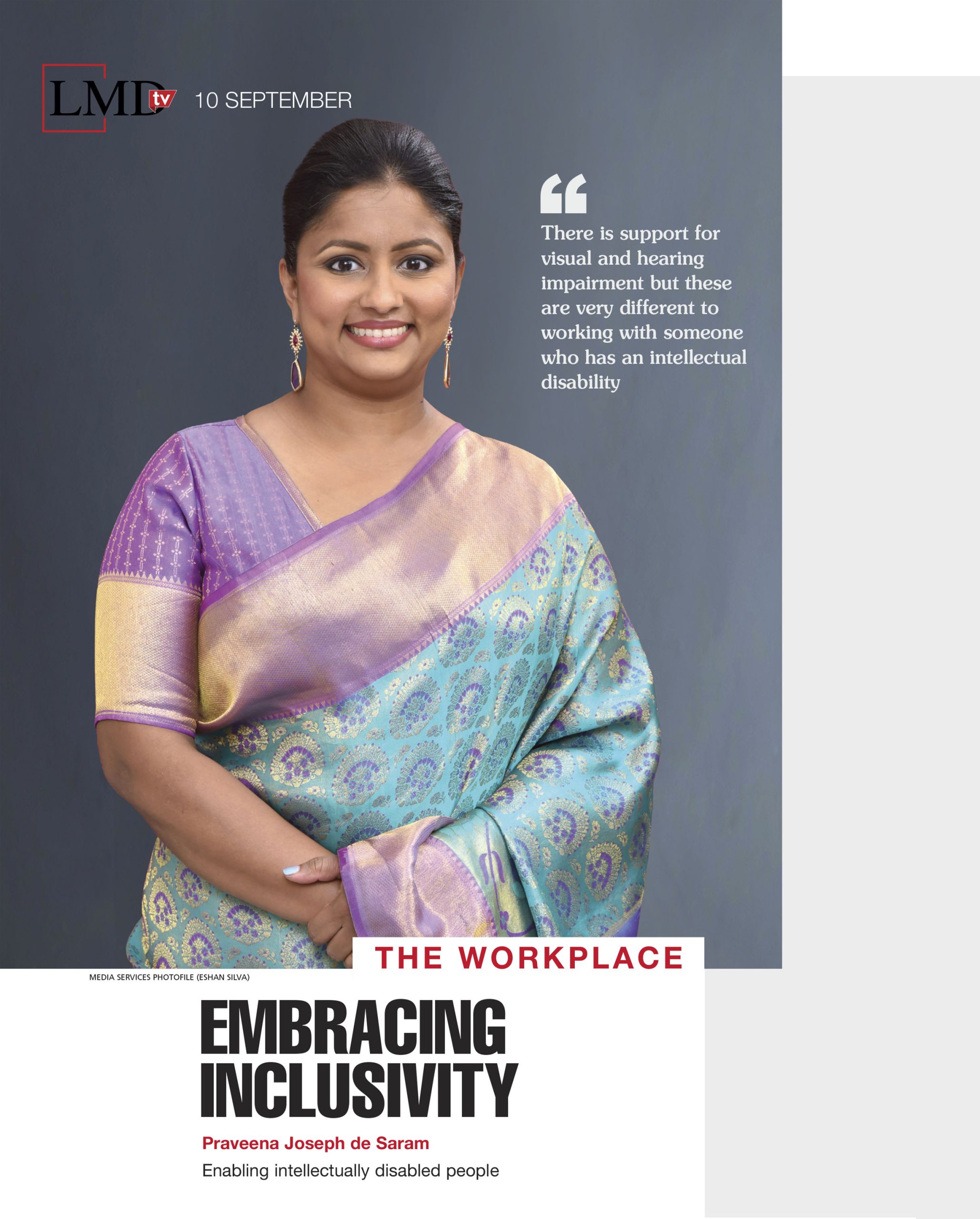

The meaning of enabling and facilitating inclusivity has evolved greatly over the years. And as Praveena Joseph de Saram said on a recent edition of LMDtv, that’s mainly about “helping all people thrive, feel valued and be able to contribute.”

Yet, when considering the majority of inclusivity practices in Sri Lanka, the definition revolves mainly around gender and encouraging more female participation in the workplace. Despite the prevalence of an educated female population, women in Sri Lanka comprise only around 30 percent of the labour force.

The Managing Director of the Shiranee Joseph de Saram Foundation (SJDSF) asserted that the focus should be about “setting the stage to include everyone, especially people with disabilities.”

De Saram continued: “Sri Lankans have had to face a ridiculous number of shocks in their lifetimes. So it’s difficult to focus on the most marginalised when pretty much everyone is enduring some kind of problem or deprivation. Another barrier is language, which plays a key role in understanding of the concept of inclusion and disability.”

She added that unlike English terminology, which is intuitive, Sinhalese and Tamil terms may not be easy to understand. In Sri Lanka, the concept of disability revolves mainly around physical impairment.

“There is support for visual and hearing impairment but these are very different to working with someone who has an intellectual disability. A lot more awareness, adaptation and preparation is needed. It’s a lack of awareness and support rather than intentional exclusion,” she noted.

De Saram explained that those with intellectual disabilities are people with cognitive difficulties. And she added that this is usually defined as having an IQ under 90, and includes conditions such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and autism.

She also revealed that “according to our own research, only about three percent of people with disabilities actually complete their education, or participate in and complete any kind of vocational training. According to a UNDP report released last year, only around five percent of Sri Lankans with an intellectual disability end up in employment.”

“This five percent rarely finds opportunities in terms of formal employment, and the opportunities that exist are rather ad hoc and don’t have a structured approach. This makes the sustainability of such employment arrangements unlikely. Unfortunately, people move from one thing to another and they have very poor experiences, which results in psychological trauma,” she elaborated.

De Saram noted: “It’s not about having a charity mindset but instead, thinking about what the organisation needs and how a role can be filled by someone with an intellectual disability.”

She recommended that “enterprises carve out a role in which such a person can succeed, and establish processes and support that will help him or her thrive. It’s not easy because you need to understand where these people are coming from, their strengths and weaknesses, and what they find challenging.”

De Saram added: “After that, you will have to identify ways to support and help them succeed based on their specific skills set.”

“One of the things we see in well-meaning organisations is that because they genuinely want to push the idea of inclusion, they try to fit people with disabilities into very visible roles – like placing someone with a speech impediment as a receptionist. The ensuing situation will be extremely demotivating for all parties in the equation,” she observed.

Those with intellectual disabilities bring very specific strengths to the table.

“For instance, they may excel in roles that require extensive attention to detail and perhaps need a lot of regularity. The space for opportunities can range from production and data entry to hospitality,” she explained, adding that while there are many options, the key lies in the creativity of the employer.