1962

The Coup D’Etat ’62 Ends in Disarray

Disgruntled officer corps lead conspiracy

In a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society, hidden tensions often simmer dangerously below the seemingly tranquil face of things. So to learn that the aborted putsch of 1962 – also known as the ‘Colonels’ coup’ – was driven by such subterranean factors should come as no surprise to students of history.

The immediate aftermath of Ceylon’s independence from Britain saw the upper echelons of the military being monopolised by Christians of a certain socioeconomic class.

In addition, the composition of the officer corps was lopsided in terms of the island’s demographic distribution – comprising three-fifths Christian, a fifth Tamil and another fifth Burgher – while the police was an estimated three-quarters Christian.

In response, Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike – an Anglican who had converted to Buddhism and usurped power on a nationalistic platform propped up by the Sinhala Only Act – extended his ‘Sinhalisation’ project into the military’s senior echelon to keep his election promise to the larger electorate whose majority community had felt marginalised prior to it.

The promotion of a Sinhalese-Buddhist bureaucrat over three senior Christian officers caused resentment to simmer and resignations to be submitted. And although ‘SWRD’ was assassinated on the grounds of another grouse, the frustration of the officer corps at having their career ambitions subverted came to a head under Bandaranaike’s successor – his wife.

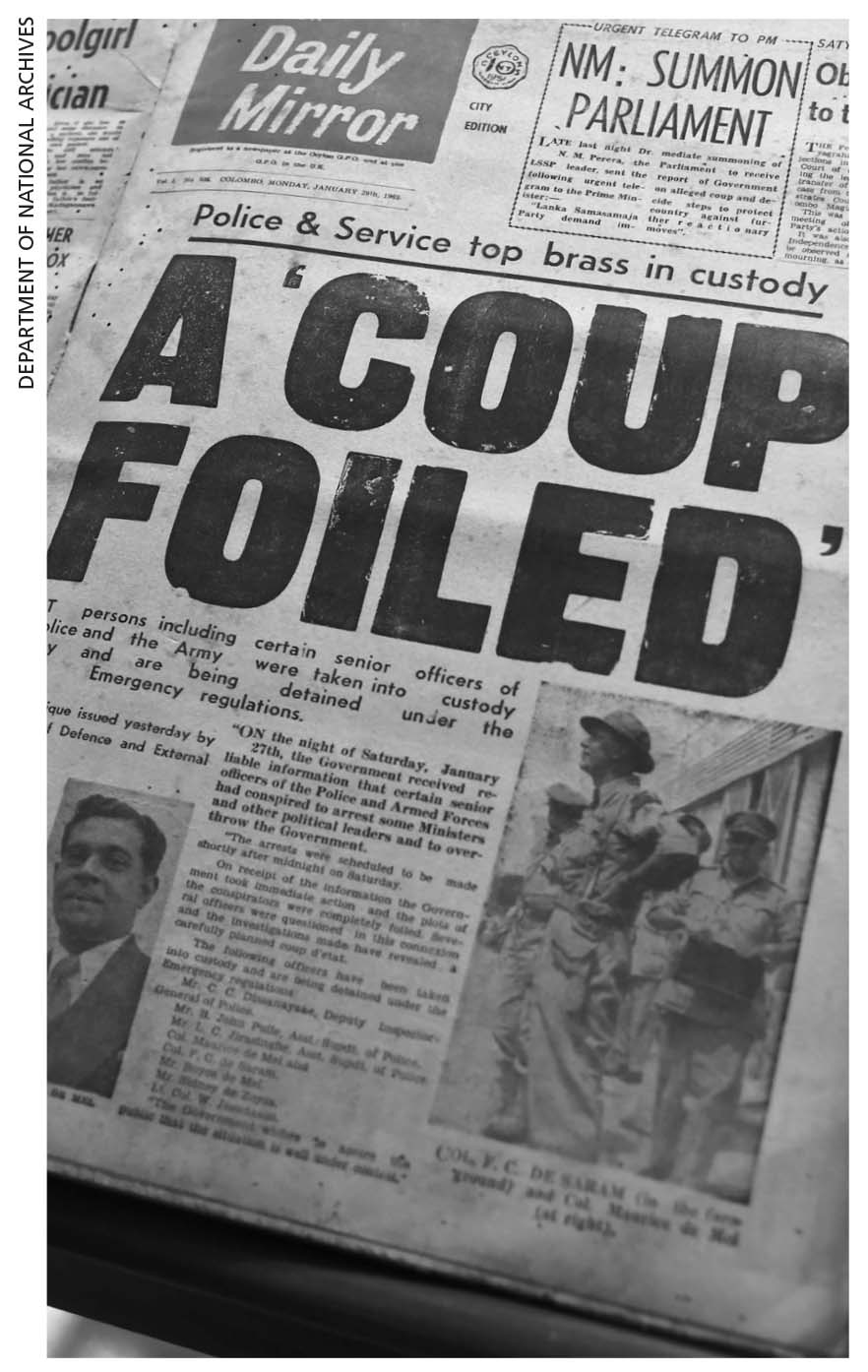

In a single night – that of 27 January 1962 – a well-knit coup d’etat had been planned by a group of army officers and senior police personnel to relieve premier Sirimavo Bandaranaike of office and replace the administration of government, which was deemed inefficient and inimical to the interest of the minorities, at least temporarily by high-ranking military officers.

The plan (‘Operation Holdfast’) was put down when a concatenation of circumstances led to the planned ouster being leaked to senior police personnel whose revelation caused the government to crackdown on the plotters.

In hindsight, it was pure fluke that stymied the coup d’etat although the state led by Felix Dias Bandaranaike – a relative of the premier – acted with alacrity to put the putsch down.

In the subsequent investigations (in all, 31 officers were arrested and scores of others sent on compulsory leave) and sackings, it was revealed that two former prime ministers too were in the know… if not complicit.

The court of three justices (sans a jury) that tried the conspirators sat for almost a year and convicted 11 of the 24 accused. They were all but one – who died in prison – released on the grounds of mistrial, following an appeal to the Privy Council, who ruled the convictions as being ultra vires the constitution, bad in law and thereby denying the conspirators a fair trial.

In a single night … a well-knit coup d’etat had been planned by a group of army officers and senior police personnel to relieve premier Sirimavo Bandaranaike of office