THE DEBT SPIRAL

Fiscal policy has become increasingly important, and a key area of focus due to rising debt levels and strained public finances in many countries, against a backdrop of heightened global uncertainty and the shock of higher trade tariffs.

The series of recent tariff announcements by the US, and countermeasures by other countries, have raised financial market volatility, weakened growth prospects and increased risks.

THE GREAT ECONOMIC BARRIER

Samantha Amerasinghe elaborates on why countries must reduce their debt levels

Major shifts in fiscal policy have become the need of the day; they will need to accommodate new and permanent increases in spending on healthcare, education and infrastructure, if countries are to dodge the looming debt crisis.

Persistently high debt in developing economies has become a barrier to economic progress. Over the last 15 years, these nations amassed debt at a record setting clip and this was exacerbated by the fastest increase in interest rates in four decades. Borrowing costs have doubled for half of all developing economies.

Although the world has so far managed to dodge a systemic financial meltdown similar to the global financial crisis in 2008, too many developing economies are now faced with looming crises. Since they’re faced with servicing their debts, many are cutting crucial investments in education, healthcare and infrastructure, which are needed for future growth.

Yet, some policy makers are opting to tempt fate by remaining hopeful that global growth will accelerate and interest rates will fall sufficiently to defuse the debt crisis.

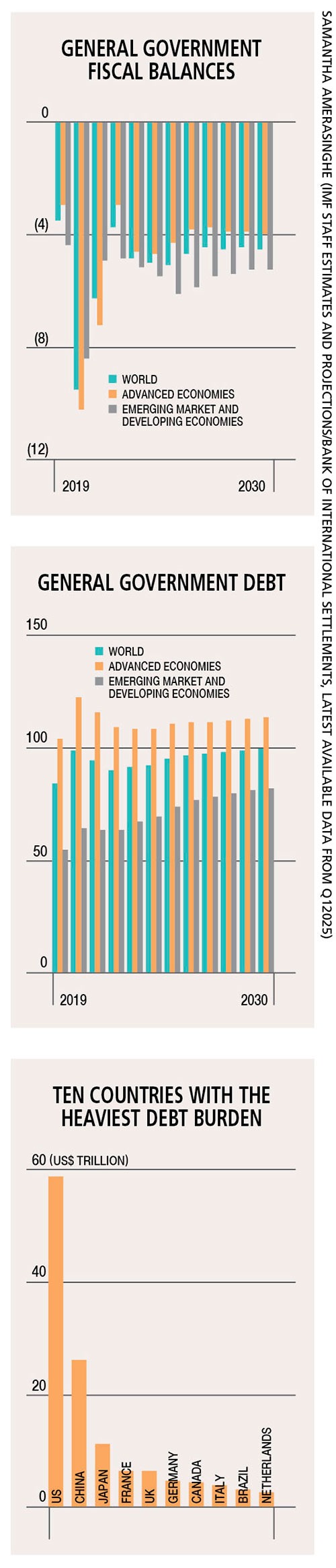

Under current policies, global growth isn’t expected to speed up anytime soon, which means that sovereign debt-to-GDP ratios are likely to climb for the remainder of this decade.

Today’s trade wars and record-breaking levels of policy uncertainty have only made the outlook worse with the consensus forecast for world growth expected to be 2.2 percent this year (though the IMF’s July estimate stands at 3%).

Interest rates in advanced economies are expected to hover at around 3.4 percent next year, which will compound developing economies’ difficulties as foreign private capital is unlikely to flow into highly indebted economies with weak growth prospects.

According to its latest Fiscal Monitor, the International Monetary Fund warns that global public debt could increase to 100 percent of the world’s GDP by the end of the decade if current trends continue. This rising public debt-to-GDP ratio reflects renewed economic pressures as well as the consequences of pandemic related fiscal support.

On a positive note, though it remains at an elevated level, global debt has stabilised as the continued reduction in private sector lending has offset greater borrowing by governments.

Total debt was above 235 percent of global GDP in 2024, according to the latest update of the IMF’s Global Debt Database.

Currently, public debt is at nearly 93 percent of the world’s GDP, according to the IMF database. Total debt increased marginally to US$ 251 trillion, of which public debt stands at slightly over 99 trillion dollars. The evolution of public debt over the past five years has diverged widely across countries.

Notable differences are evident with the US and China playing a dominant role in shaping debt dynamics across the world. Meanwhile, debt and deficit levels in many countries are still high, and concerning by historical standards in both advanced and emerging economies.

Last year, government debt in the United States rose to 121 percent of GDP (from 119% in 2023) while China saw an increase to 88 percent (from 82%).

Excluding the US, public debt in advanced economies fell by more than 2.5 points to 110 percent of GDP. Excluding China, public debt in emerging markets and developing economies edged down to under 56 percent on average.

The persistently high global fiscal deficit, which is averaging around five percent of GDP, is the main driver of rising public debt.

This deficit still reflects legacy costs such as subsidies and social benefits due to the pandemic, as well as rising net interest costs. Declining private debt levels in the US are due to companies borrowing less with strong balance sheet positions and cash holdings also contributing to lower corporate borrowing.

In China, the key driver of increasing private debt stems from an ongoing weakness in the property sector. Meanwhile, household debt has fallen as mortgage demand has waned due to concerns over employment and growth in wages.

In other large emerging markets and developing economies, rising private debt reflects a range of factors including high interest rates and their impact on non-performing loans (as in Brazil), better near-term growth prospects in countries such as India, and corporate mergers and acquisitions.

It’s imperative that governments prioritise gradual fiscal adjustments within a credible timeframe to reduce public debt.

These alarming debt trends can be eased if governments create an environment that boosts economic growth and reduces uncertainty, and places an emphasis on rebuilding capacity to spend and respond to new pressures – and many other types of economic shocks.