Environmental Compliance

Rohan Pethiyagoda sheds light on the difference between rational and ideological environmental activism

On an edition of LMDtv not long ago, the highly respected environmentalist and taxonomist Rohan Pethiyagoda noted that “every country requires an optimal socioeconomic standard, which developed economies have managed to achieve.”

He added that “developed countries have higher environmental standards than their underdeveloped counterparts, implying that economic development sets a positive pathway to enact environmental best practices.”

He added that “developed countries have higher environmental standards than their underdeveloped counterparts, implying that economic development sets a positive pathway to enact environmental best practices.”

The most notable harm stems from poverty, in his view: “Financial impairment puts people at a disadvantage, making it much more difficult for these socioeconomic groups to be as environmentally compliant as the rest of their peers.”

Environmental compliance requires money. For instance, wind farms are costly as they need electricity storage and batteries. The same applies to solar energy.

California is an example of renewable electricity having high energy bills. Pethiyagoda explained: “A country like ours can’t afford to pay high prices for electricity, which is why we rely on cheaper alternatives such as coal. When people struggle to make ends meet, they aren’t able to prioritise environmental needs.”

Poverty is a major disabler in society and needs to be addressed. When people reach a certain threshold of affluence, they’re able to divert more attention to the environment. The stark contrast between a developed and developing nation is akin to a fully grown adult who has reached a certain stage of stability compared to a teenager experiencing changes year by year.

“Developing countries are similar to teenagers; they’re growing fast, consuming a lot and disorderly,” Pethiyagoda said on the weekly show.

“Developing countries are similar to teenagers; they’re growing fast, consuming a lot and disorderly,” Pethiyagoda said on the weekly show.

The realities of developing nations are very different from those of their developed counterparts and this must be considered when working on environmental management plans, as he pointed out: “It’s not effective to apply the same standards to two vastly different scenarios.”

Nevertheless, complying with environmental standards is essential – and environmental activism is fundamental for society as a whole.

For example, if not for the activism and efforts of the likes of Vidya Jyothi Prof. Sarath Kotagama and Thilo Hoffmann in the 1970s – who led the charge against the destruction of the Sinharaja and Kotagala copper forests – they would have disappeared by now.

Which is why environmental activism is vital.

But half a century later, activism has taken a diametrical form where it is poorly informed. “This is perhaps why scientists no longer associate themselves with activism since they find it distasteful,” Pethiyagoda observed.

He continued: “Consequently, activism has become quite misplaced and hysterical where people tend to object to every development project – be it a power plant, a hydroelectric project or an irrigation system.”

He continued: “Consequently, activism has become quite misplaced and hysterical where people tend to object to every development project – be it a power plant, a hydroelectric project or an irrigation system.”

“The Upper Kotmale Dam involving 50 hectares of land drew massive protests across the country,” Pethiyagoda recalled, adding: “Protesters were burning tyres and participating in rallies to stop the project.”

But as he explained, these fears may have been misplaced: “Over the past 15 years, it doesn’t seem to have caused any harm. The Uma Oya Hydropower Complex is another project that instigated a similar response.”

There is a tendency for environmental activism to be excessively hyped. And as Pethiyagoda observed, “this attitude is detrimental since the government – or any administration – stops listening.”

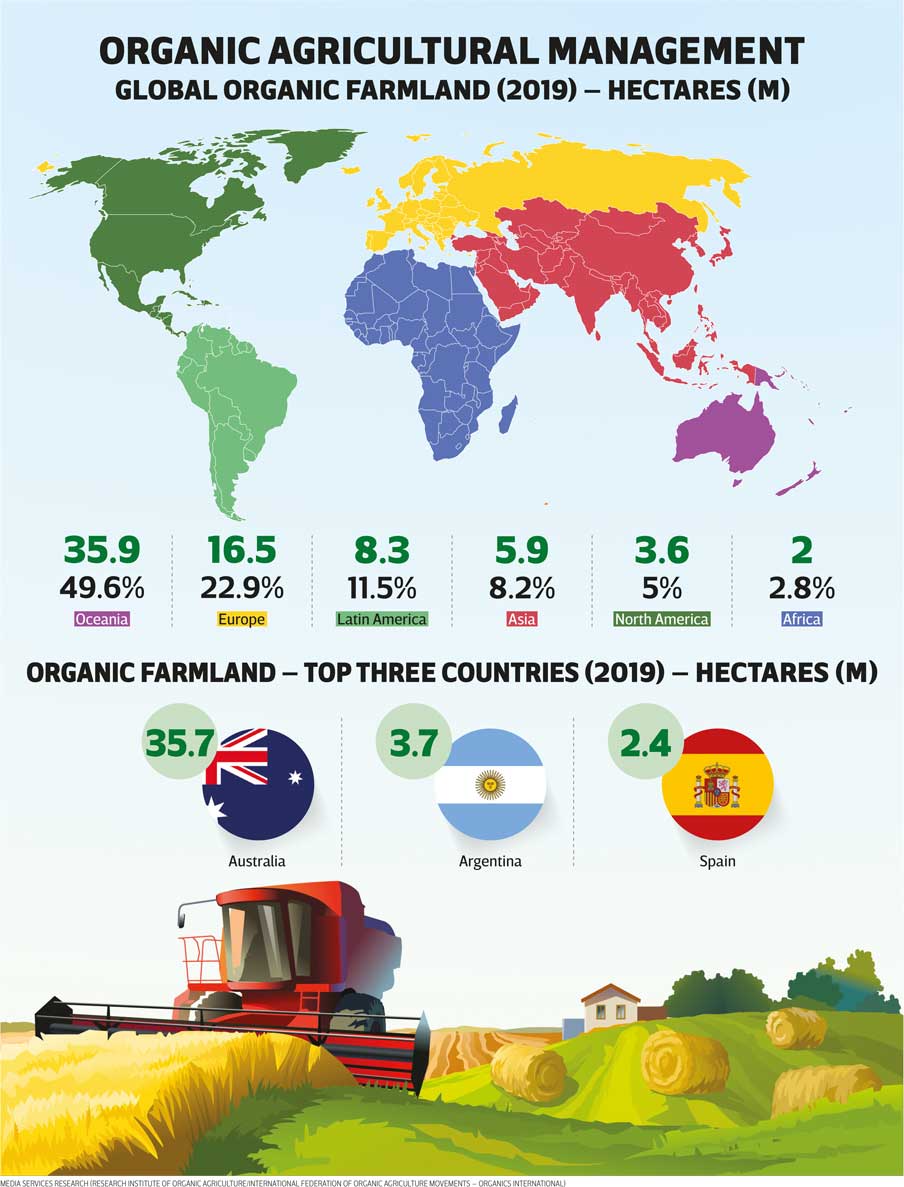

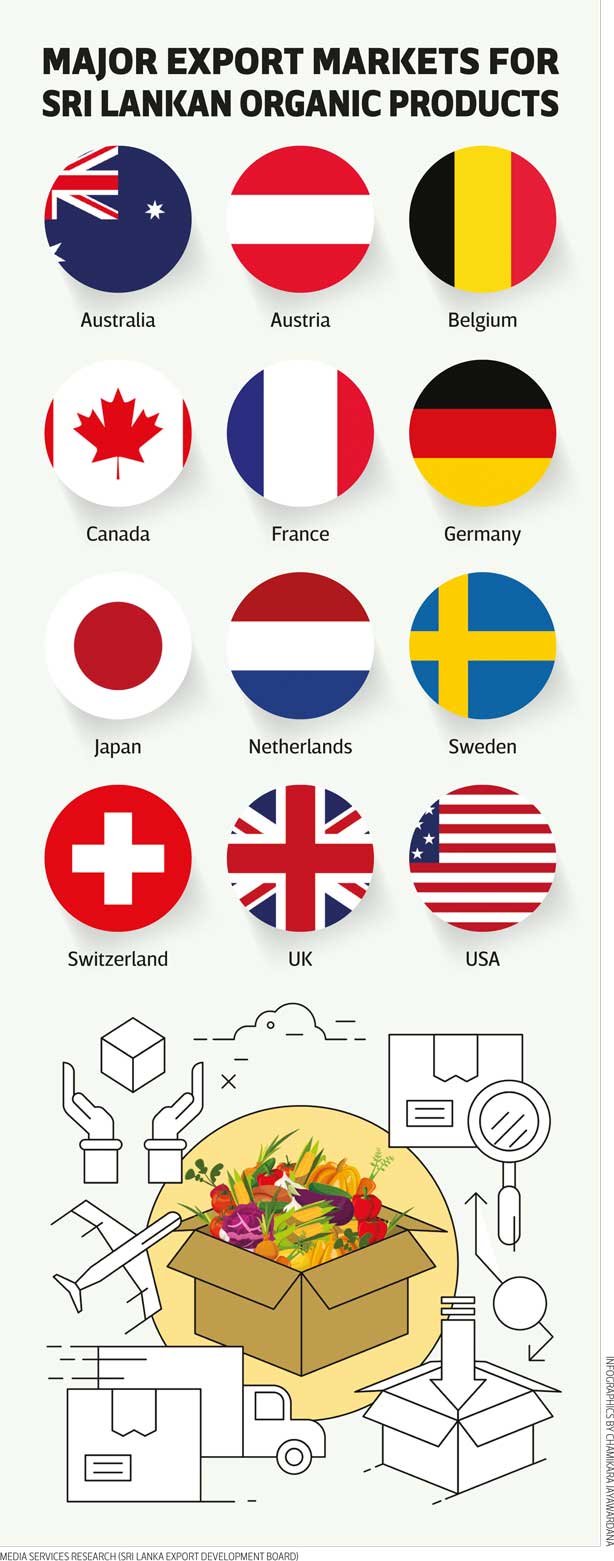

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s drive to become the first country to produce 100 percent organic agriculture will have several consequences.

Such an approach generates yields that are 30 percent lower than conventional agriculture, which is why the latter is more widespread. This shift would lead to financial losses unless premium prices can be charged to compensate for it.

In addition, farmers need to obtain organic certified labels, which poses numerous challenges as Sri Lanka has around one million rice farmers and about 400,000 tea smallholders.

Pethiyagoda asserted that “assuming that global market demand exists for the 300 million kilogrammes of organic tea Sri Lanka intends to produce annually – which is doubtful – all these smallholders need to get certified by paying US$ 300 a year (circa Rs. 60,000) to one of the seven MNC NGOs that operate in Sri Lanka.”

Pethiyagoda asserted that “assuming that global market demand exists for the 300 million kilogrammes of organic tea Sri Lanka intends to produce annually – which is doubtful – all these smallholders need to get certified by paying US$ 300 a year (circa Rs. 60,000) to one of the seven MNC NGOs that operate in Sri Lanka.”

Affordability remains a question too.

Can these farmers – most of whom are living on the edge of poverty – pay an amount equivalent to almost two months of their income for certification?

Pethiyagoda argued that “they’re not the best educated to understand the 85 pages of small print to comply with the SLS 1324 standard.”

Indeed, these factors raise questions about the practicality of Sri Lanka’s aspiration to become an organic brand.

Failure is also a risk, as he pointed out: “Even if one of these 400,000 smallholders cheats by not complying with the organic standards, it can tarnish the reputation of the entire country and therefore, this programme requires considerable thought before implementation.”

Failure is also a risk, as he pointed out: “Even if one of these 400,000 smallholders cheats by not complying with the organic standards, it can tarnish the reputation of the entire country and therefore, this programme requires considerable thought before implementation.”

Meanwhile, it’s noteworthy that many corporates allocate CSR budgets to undertake social projects while environmental programmes warrant only a fraction of this.

Biodiversity Sri Lanka is one of the main platforms that many corporates have subscribed to. It conducts projects pertaining to biodiversity and environmental conservation. According to Pethiyagoda, companies that are keen on pursuing environmental projects can partner such initiatives.

Corporates are also capable of doing their part.

An example of this is the tea industry’s regional plantation companies collectively managing about 350,000 hectares of agricultural land. It is a fact that the industry has the management capacity to administer environmental projects such as forest conservation, sustainable forestry and so on.

“Sri Lanka has come a long way from the past with there being more environmentally conscious citizens,” Pethiyagoda acknowledged, elaborating: “Transferring technical scientific knowledge to the Sinhala medium in the form of popular publications in the 1990s acted as a catalyst for breeding a remarkable new environmental awareness among the people.”

“Sri Lanka has come a long way from the past with there being more environmentally conscious citizens,” Pethiyagoda acknowledged, elaborating: “Transferring technical scientific knowledge to the Sinhala medium in the form of popular publications in the 1990s acted as a catalyst for breeding a remarkable new environmental awareness among the people.”

The increase in youth participation in environmental activism today is commendable but Sri Lanka is short of funds to support these prgrammes. In his opinion, the ideal solution is to generate revenue from related avenues and divert these funds to worthy causes.

“For example, the hydropower generation of about 40 gigawatt hours of hydroelectricity is valued at 250 million dollars a year,” remarked Pethiyagoda, stating that “if around three percent of this amount (i.e. half a billion rupees a year) is set aside for such causes, it will be a fantastic windfall.”

According to him, “many environmental movements are based on ideologies rather than science.” In his view, these include organic food – which could be considered a costly ideology not backed by science – while nuclear energy is another; it is one of the cleanest and sustainable energy providers but attracts opposition on grounds of safety whereas it’s safer than coal in terms of annual deaths.

Summing up his take on the big picture, Pethiyagoda remarked that “environmental management requires a shift from regulation and policing to something that comes directly from the people.”