SPOTLIGHT

MECHANICS OF MODERNITY

DISSECTING THE CONTEMPORARY ANATOMY

BY Archt. Chiranthi Warusawitharana

At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) lies one of the most important photographs of the 20th century, titled The Steerage by Alfred Stieglitz, photographed in 1907. The Steerage is considered Stieglitz’s signature work and was proclaimed by the artist as his first modernist photograph. It marks Stieglitz’s transition away from painterly prints of symbolism to a more straightforward depiction of the quotidian life of modernity.

Steerage is the lower section of a ship, offering minimal accommodation for the lowest fare passengers, in this case allocated for Europeans who were rejected from entering America. Alfred Stieglitz himself was a first-generation German Jewish American heading to Europe for the holidays with his wife and daughter in first-class, which included the top-level observation decks, consisting of all types of travellers. In the photograph, there is a sense of the modern world, where all types of people come together, of the messy, fast-paced movement and the intensity of travel with frequent intercontinental immigration between Europe and the Americas.

The Steerage demonstrates a shift in thinking, moving away from standard Victorian pictorial photography towards the notion of modern photography. Despite the camera being invented in 1816, photographers of the early 1900s were not considered fine artists due to the use of the optical machine. In such a cultural setting, Victorian pictorialism was the term used by photographers to describe a blurring photographic style which mimicked the formal qualities of Victorian drawing and painting to make photographs socially acceptable.

For Alfred Stieglitz, the camera represented the full embrace of modernity, characterised by the involvement of machines to support every aspect of modern life. Since the pace of life was becoming faster, Stieglitz believed that the camera would be the device to document the fleeting moments of modernity.

Classifying modernity

Modernity is a period generally characterised by reliance on scientific inquiry, industrialisation, technological innovation and urbanisation. The term represents the social transformation that took place from a feudal social order to a capitalistic social order under the grand project of industrialisation, secularisation, rationalisation and individualism.

Modernism was the equivalent cultural movement that emerged in response to the social conditions of modernity. It was a global movement that transformed artistic, literary, musical and architectural thinking from the late 19th century to mid-20th century.

According to historian Eric Hobsbawm, the historical evolution of modernity can be classified into seven developmental stages: Renaissance (14th-16th centuries), Reformation Movement (16th-17th centuries), Scientific Revolution (16th-17th centuries), Enlightenment Movement (18th century), American War of Independence (1776), French Revolution (1789) and Industrial Revolution (late 18th to early 19th centuries). The Industrial Revolution marked the permanent shift from agrarian economies to industrialised societies in Europe.

Tracing modernity

Modernism is attributed to the continuous evolution of Anglo-European philosophy and related thinking. The significance of modernity is incomprehensible without the understanding of the lineage of western thinking. A comprehensive body of knowledge, spanning from the period of antiquity of the Greek and Roman eras, to the medieval period, the Renaissance and leading up to the Enlightenment, remains unbroken.

The medieval period which lasted from the 5th to the 15th centuries in Europe, defined by Gothic architecture, demonstrated a time of religious dogma where scholastic theologians set boundaries for the social conduct of their congregation. Early Renaissance acknowledged this social limitation and the detrimental impact it had on human knowledge. Renaissance society was not anti-Christian but rather anti-dogmatic.

During the Renaissance, there was keen interest in re-examining the mechanics of the trivium from antiquity. The trivium consisted of the three mechanics for thought: grammar, logic and rhetoric, which were the linguistically bound foundational canons for the training of human cognition. The trivium set the principles for a person to learn how to think. The quadrivium assumes that human thought had been quantified to productive means and built into the four bodies of knowledge consisting of arithmetic, astronomy, music and geometry.

It is said that if one is not trained in the trivium, the questions posed during ideation will create trivialities, misleading the thinker. Proponents of Renaissance humanism sought to unburden themselves from trivialities, as they wanted to become self-guided thinkers. They looked for rhetorical techniques in particular Greek and Roman writings related to the study of myth, poetry and historical accounts. For example, they studied the mechanics of memory – a Greek techne called ars memoriae (building of memory places) that trained the mind to visualise spatial structures to store vast amounts of information using memory associated objects and retrieving them using the individual’s memory impressions.

Therefore, the essence of the Renaissance lay not in any sudden discovery of ideas forgotten from the classical Greek or Roman civilisation, but rather in the development of the trivium and adopting it for their processes of ideation. The abundant use of the trivium during high Renaissance paved the way for more mathematically precise mapmaking, which made the world seem capturable on paper. The invention of the linear perspective by architect Filippo Brunelleschi enabled any idea for drawing, painting, sculpture or architecture to be interchangeable from 2D to 3D and vice-versa. The classical architectural treatise De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building) was written during the Renaissance by architect Leon Battista Alberti, leading to the use of these principles in Europe and the Americas for the next 300 years.

Glazing modernity

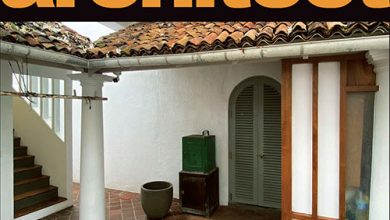

The first modern, reminiscent use of glass in a pre-modern era was seen in Hardwick Hall, a country house in Derbyshire from the Elizabethan era, built between 1590-1597. It was designed by architect Robert Smythson for Elizabeth Talbot, the Countess of Shrewsbury, who was the richest woman in England after the Queen.

Hardwick Hall showcased concepts for domestic architecture leaning towards the modern and invited a new way in which life could be led in a great house. The chimneys of the mansion were built into the internal walls of the structure, allowing for larger windows without weakening the exterior walls. Early modernist architects took this a step further by looking to develop strategies that enabled a recessed structure that could free the external walls for the play of glass.

Inspired by the astonishing natural light brought into rooms by large glass panels, it became fashionable to use glass in residential architecture during the Victorian period that followed. Despite the design of Hardwick Hall being an intentional display of wealth, at a time when glass and window tax was charged based on the number of windows, the public adored it, coining the rhyme: ‘Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall.’

By 1845 the Hardwick Hall effect was influential enough to demand the lifting of the glass tax in Britain and the window tax was also repealed by 1851. Since the Elizabethan embrace of the glass panels at Hardwick Hall, it took another 350 years for the American modernist architect Philip Johnson, to device the glass panelling and achieve the sophisticated spatial design of The Glass House.

Mechanising modernity

By the mid-18th century, many Europeans were critical of blindly romanticising nature and the excessive use of ornamentation in the avant-garde architectural style of Baroque. Society at the time exuded pompous grandiosity representing the emerging values of the bourgeoisie – the wealthy merchant class that grew into power as the manufacturing industry expanded during the industrial revolution.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote ‘God is dead’ in 1882. The statement suggests that society has naturally lost the ability to believe in God and the idea of a universe governed by definitive physical laws discovered by science is more credible than relying on the idea of divine providence. The Enlightenment movement instigated the practices of modernity and attempted to develop the necessary sciences to control ‘nature’ for the benefit of society. Modernity is in fact a counter-Renaissance movement that brought the creative energies of the Renaissance under control through the invention of practical, rational science.

The Enlightenment ideas that served modernity can be traced back through the nine areas of philosophical debates: reason and rationality (Descartes, Kant, Kierkegaard, Heidegger and Russell), human dignity and freedom (Montesquieu, Locke and Nietzsche), society, state and law (Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau), ontology and epistemology (Descartes, Spinoza, Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Sartre and Ryle), ethics, morality and divinity (Descartes, Spinoza, Nietzsche and Russell), secularism (Machiavelli, Weber, Holyoake, Voltaire, Spinoza, Locke, Jefferson and Russell), scepticism (Descartes, Spinoza, Berkeley and Hume), ideas on science, technology and industrialism (Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Bacon, Newton, Darwin, Marx, Durkheim and Heidegger) and human sexuality (Freud, Wollstonecraft and Beauvoir).

This constellation of ideas and scientific procedures were extensively codified in the nation building of the United States, normalising the large scale industrial mechanisation and mass production of goods. In 1932, the Museum of Modern Art International Exhibition curated by Philip Johnson and American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, was instrumental in introducing the works of the Bauhaus architects and other European modernists to the American cultural consciousness. The industrial exhibitions that followed, such as the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago (1933) and the New York World’s Fair (1939) themed Democra-city, solidified the project of modernity in the psyche of the American public, ushering a brave new world with its fair share of dystopian realities.

Modern Aesthetic

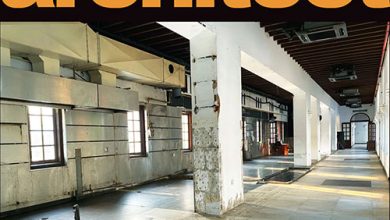

Modernist architecture is associated with an analytical approach to the function of buildings, the rational use of mass-produced materials and structural innovation enabling the free plan. Architects collectively attempted to develop an emancipatory architectural language away from the bourgeoisie representations of power, such as land ownership consisting of acres of picturesque gardens.

The ground floor was symbolically lifted on ‘pilotis’ so that the cell like habitation does not touch the politicised ground. The rooftop was turned into a garden replenishing the lost vegetation. All forms of cultural ornamentation were removed and the buildings painted in white or neutral colours creating the minimalist style. Concrete became the popular material with seamless spaces that created a non-referential architecture, with no reference to past cultural values or contextual origin. The architecture was designed to frame the distant horizon, making the gesture a global phenomenon.

The E-1027 house was the first of its kind, developed by the Irish interior designer Eileen Gray between 1926 to 1929 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin overlooking the French Riviera. Eileen Gray reimagined every aspect of the modernist home – she tested new materiality for the interiors by designing lampshades, furniture and fabric designs; working out the house from inside out. The spatial concepts for a modern bedroom, kitchen, toilet and wardrobe were all resolved in E-1027 and the concrete structure that held all these spaces consisted of a rooftop garden that looked to the horizon.

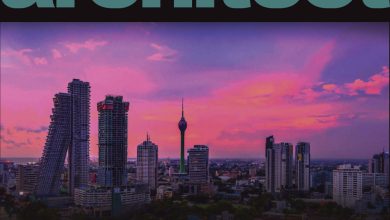

American Modernism

American modernism was different from European, due to the sheer scale of societal aspirations and state incentives to practice industrial ingenuity, influenced by transatlantic geopolitics. Some of the earliest skyscrapers were built in New York and Chicago between 1884 and 1945. The steel structural systems used were of mass-produced modular prefabricated kit-of-parts that celebrated America’s industrial inheritance. By the mid-20th century, American architects broke away from the rectilinear geometry of the steel and glass structures to explore new shapes and fluid volumes.

The concrete structure designed with expressive spans for the Trans World Airlines (TWA) Terminal at JFK Airport by architect Eero Saarinen, for example, abandons the European sensibility associated with maintaining the neutrality of the modernist box. American architects were concerned with the �volumetric conceptualisation of space primarily assisted by architectural modelling as opposed to drawing. This intellectual exploration transformed American architecture to the post-modern deconstructive expression inspired by the writings of Jacques Derrida.

P.S.

European imperialism caused the wicked problem of post-independent nation building, leaving the natives with an identity crisis that can never fully be decolonised. In addition, the term critical regionalism was the label given by western architectural experts to describe modernist practices in Asia, setting a restrictive vocabulary for Asian architects to communicate their work to global audiences. The resulting insecurities may have led the Sri Lankan architectural fraternity to align with vernacular sensibilities, which were less concerned with responding to matters of the architectural canon or local ingenuity.

If architecture is expected to express the spirit of the time, in doing so, it may unintentionally signal the numbing of that time. The generational numbing signalled by the vernacular cosmopolitanism is palpable. Architect Valentine Gunasekara points out the loss incurred by the ones who overlook the modern trivium. He says: “One of the things that we lost in going back to the vernacular is that the deliberate way of designing, using modules or a conscious understanding of the way form is arranged or can evolve. It’s no longer there in a lot of architecture… We lost the pursuit of that pattern, which you create and vigorously act out in the project. And we kind of collapsed into spatial organisation… into space planning actually… with a known vernacular… The plan is nothing but a ‘space-plan,’ because you have no idea what the volumes are doing. You have absolutely no concept!” (V. Gunasekara in an interview conducted by Anoma Pieris (2007), pg.78).

REFERENCES

1 Terry, J. S. (1982). The Problem of ‘The Steerage.’ History of Photography, 6(3), 211-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.1982.10443043

2 Delanty, G. (2013). Formations of European Modernity: A Historical and Political Sociology of Europe (1st ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

3 Xhexhi, K. (2024). Modernity and Architecture: The Evolution of Thought, Innovation and Urbanism from the Renaissance to the Present. In All Sciences Academy: 5th International Conference on Engineering and Applied Natural Sciences (pp. 242-249). Konya, Turkey, August 25-26.

4 Hobsbawm, E. J. (1962). The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789-1848 (1st ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

5 Toulmin, S. (1990). Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (1st ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

6 Czejka, E. (2019, November 4). WIA Interview – Vera Bühlmann: What is Architecture? [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tePjOCj3lgM

7 Leithart, P. (2005). Renaissance and Modernity. Theopolis Institute. https://theopolisinstitute.com/leithart_post/renaissance-and-modernity-2/ [Accessed 20 December 2024].

8 Mike. (2022). National Trust Hardwick Hall: History. https://www.xploreheritage.com/post/national-trust-hardwick-hall-history-and-photos [Accessed 17 December 2024].

9 Aure, M. (2023, August 3). Inside The Iconic Glass House. Open Space Media LLC [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVDjKshoGkA

10 Žižek, S. (2003). The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity (1st ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

11 Mondal, L. K. (2014). Modernity in Philosophy and Sociology: An Appraisal with Special Reference to Bangladesh. Philosophy and Progress, 51(1-2), 123-160. https://doi.org/10.3329/pp.v51i1-2.17682

12 Curtis, A. (2021). The Century of the Self [Film]. RDF Television; BBC; BigD Productions. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eJ3RzGoQC4s

13 The Shelfist. (2020). Le Corbusier, Eileen Gray and the E1027 House: Unveiling the Architectural Controversy. https://theshelfist.com/le-corbusier-eileen-gray-and-the-e1027-house-unveiling-the-architectural-controversy/

14 Wilkinson, T. (2016). Eileen Gray (1878-1976). The Architectural Review. EMAP Publishing Limited. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/eileen-gray-1878-1976

15 Pieris, A. (2011). The Engineer and the Bricoleur: Revisiting a Familiar Opposition in Sri Lankan Architecture. South Asia Journal for Culture, 4, 20-40. https://patitha.lk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SAJC-Vol-4-2010.pdf

16 Bhabha, H. K. (1996). Unsatisfied Notes on Vernacular Cosmopolitanism. In P. C. Pfeifer and L. Garcia-Moreno (Eds.), Text and Narration (pp. 191-207). Columbia, SC: Camden House.

17 Pieris, A. (2007). Modernism at the Margins of the Vernacular: Considering Valentine Gunasekara. Grey Room, 28, 56-85. https://doi.org/10.1162/grey.2007.1.28.56