Last year, Sri Lanka’s rubber industry recorded US$ 1.2 billion in exports with 70-80 percent revolving around tyres, 20-30 percent handed in by gloves and the rest by other products.

Last year, Sri Lanka’s rubber industry recorded US$ 1.2 billion in exports with 70-80 percent revolving around tyres, 20-30 percent handed in by gloves and the rest by other products.

“The tyre export sector is valued at 800-1,000 million dollars of which nearly 85 percent consists of the export of solid tyres. Most of the top international brands are represented in Sri Lanka – Michelin and Trelleborg, and other brands such as GRI and Eurotech, which are the largest in terms of solid tyre manufacturing companies,” reveals Ravi Dadlani.

AN OPPORTUNITY TO STRETCH

Ravi Dadlani believes that our rubber exports can be a key contributor to the economy

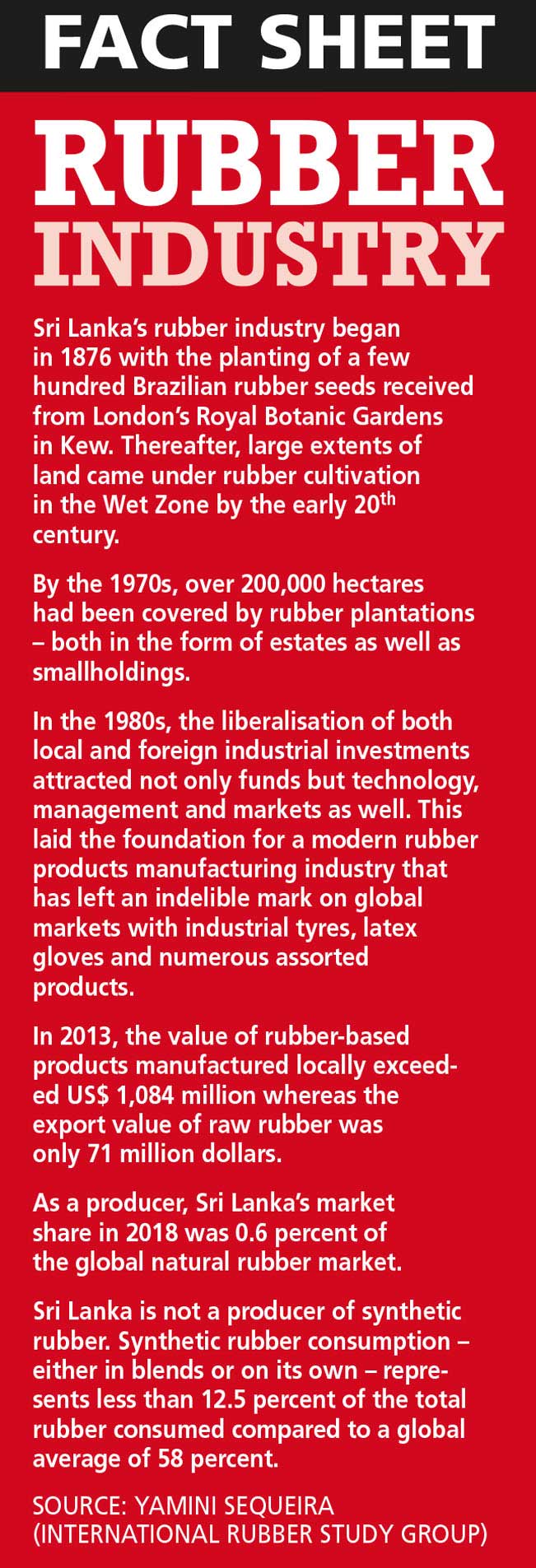

Compiled by Yamini Sequeira

And the Managing Director of CEAT and Chairman of the Sri Lanka Association of Manufacturers and Exporters of Rubber Products (SLAMERP) clarifies: “The local pneumatic tyre export industry consists of CEAT, Ferentino and DSI.”

PERFORMANCE Although rubber exports dodged the ‘pandemic bullet,’ it did encounter hardships.

“The industry faced several issues when it came to the pandemic such as executing orders, on time delivery and ensuring workers could reach factories. Import restrictions and the rupee devaluation further impacted the industry,” Dadlani discloses.

He adds: “Today, a percentage of natural rubber and other inputs are also imported. In the case of pneumatic tyres, almost 75 percent of raw materials are imported; and in the case of solid tyres, 25-30 percent of raw materials come from overseas. Therefore, supply chain disruptions were a concern.”

In terms of value nevertheless, tyre exports sustained the previous year’s performance – apart from a marginal dip in volumes.

Among the major strengths of this industry have been the availability of natural rubber locally, coupled with GSP and GSP Plus benefits, in Europe and the US. The presence of skilled labour is also a clear advantage.

Among the major strengths of this industry have been the availability of natural rubber locally, coupled with GSP and GSP Plus benefits, in Europe and the US. The presence of skilled labour is also a clear advantage.

Dadlani elaborates: “When tyre manufacturing was established by international companies in Sri Lanka decades ago, the country was producing close to 120-135 million kilogrammes of rubber. Over the years however, the availability of natural rubber in Sri Lanka has declined. And even though the rubber products manufacturing industry in its entirety requires 120-130 million kilogrammes of natural rubber, Sri Lanka now produces only 75-80 million kilogrammes.”

RESOURCES Tracing the decline in natural rubber, he notes that “rubber is a commodity and Sri Lanka has lacked the ability to manage fluctuation in commodity prices.”

“Instead, people take a narrow view and sell rubber plantation lands – much like in the case of coconut estates. Since a rubber tree takes six years before it produces its first harvest, farmers must take a long-term view,” he urges.

Dadlani blames the decline in the output of natural rubber on not replenishing plantations and diversifying to new regions, which will be suitable for expanding the extent of rubber estates in the country. Ironically, a clear road map for the industry is in place.

“SLAMERP, together with the Rubber Research Institute of Sri Lanka, the Plastics & Rubber Institute of Sri Lanka (PRISL) and the Sri Lanka Society of Rubber Industry – with the help of expert Dr. Lakna Paranawithana – developed a rubber master plan. It was presented to policy makers five years ago with clear directives for improving productivity in the plantations but no action was taken by them thereafter,” Dadlani maintains.

In addition, rubber harvesting countries such as Thailand, Vietnam and India boast higher productivity of about 2,200 kilogrammes a hectare while Sri Lanka achieves only 700-800 kilogrammes. Some of the better harvesting systems and methodologies adopted by these countries were never embraced by Sri Lanka, which has led to low productivity.

However, the sector is ramping up rubber production with renewed vigour on nearly 405 hectares of land in Buttala and Moneragala.

“From our perspective, there is enough scope to increase replanting trees that need to be replenished, improve productivity and expand plantation areas,” he emphasises.

Dadlani believes the tyre export sector has the potential to triple exports and that businesses are making the right moves to expand capacity while anticipating higher output. He adds that the pandemic benefitted the export of rubber gloves – a segment that’s showing immense potential.

Dadlani believes the tyre export sector has the potential to triple exports and that businesses are making the right moves to expand capacity while anticipating higher output. He adds that the pandemic benefitted the export of rubber gloves – a segment that’s showing immense potential.

“Customers prefer the quality of gloves manufactured in Sri Lanka compared to larger exporters such as Malaysia and Thailand,” he avers.

CHALLENGES Dadlani says he is lost for words about the current economic challenges but highlights the adverse impact of the forex crisis on exporters as well as local businesses.

“Availability of forex is a key factor for us to keep the industry going. The second largest challenge is the power crisis because some of the large machinery can’t be run by generators and needs grid power,” he points out.

He also laments the scarcity of diesel and other types of fuel as transportation of workers to factories is hampered. Another roadblock has been logistics with regard to the availability of containers as ships are bypassing Sri Lanka due to its import restrictions. The increase in freight costs is yet another global phenomenon.

On a positive note however, besides rubber and apparel exports, he sees immense potential for the exportation of seafood and believes this sector should be upscaled.

“We also need to implement the National Export Strategy (NES), which was designed to increase and diversify the export basket. As for the rubber industry, a dedicated zone for foreign direct investment (FDI) has been proposed under the master plan to attract new investors but these initiatives have been delayed,” he posits.

And he continues: “We need to also reduce transaction costs through trade facilitation to be more competitive globally.”

Dadlani calls for a consistent policy framework: “In 2019, Sri Lanka’s import bill was around US$ 19 billion including vehicle imports amounting to some four billion dollars. If you subtract vehicle imports, the import bill was US$ 15 billion. In 2021, Sri Lanka’s import bill was 21 billion dollars – and without vehicle imports at that! This implies an increase of six billion dollars in import consumption…”

While Dadlani’s forecast for the economic situation in the short and medium terms is subdued, he believes that if the right policies addressing key issues are implemented, the economy can be turned around in the longer term.

The interviewee is the Managing Director of CEAT and Chairman of the Sri Lanka Association of Manufacturers and Exporters of Rubber Products (SLAMERP)

This content is available for subscribers only.