REGIME CHANGE

MUGABE’S FALL FROM GRACE

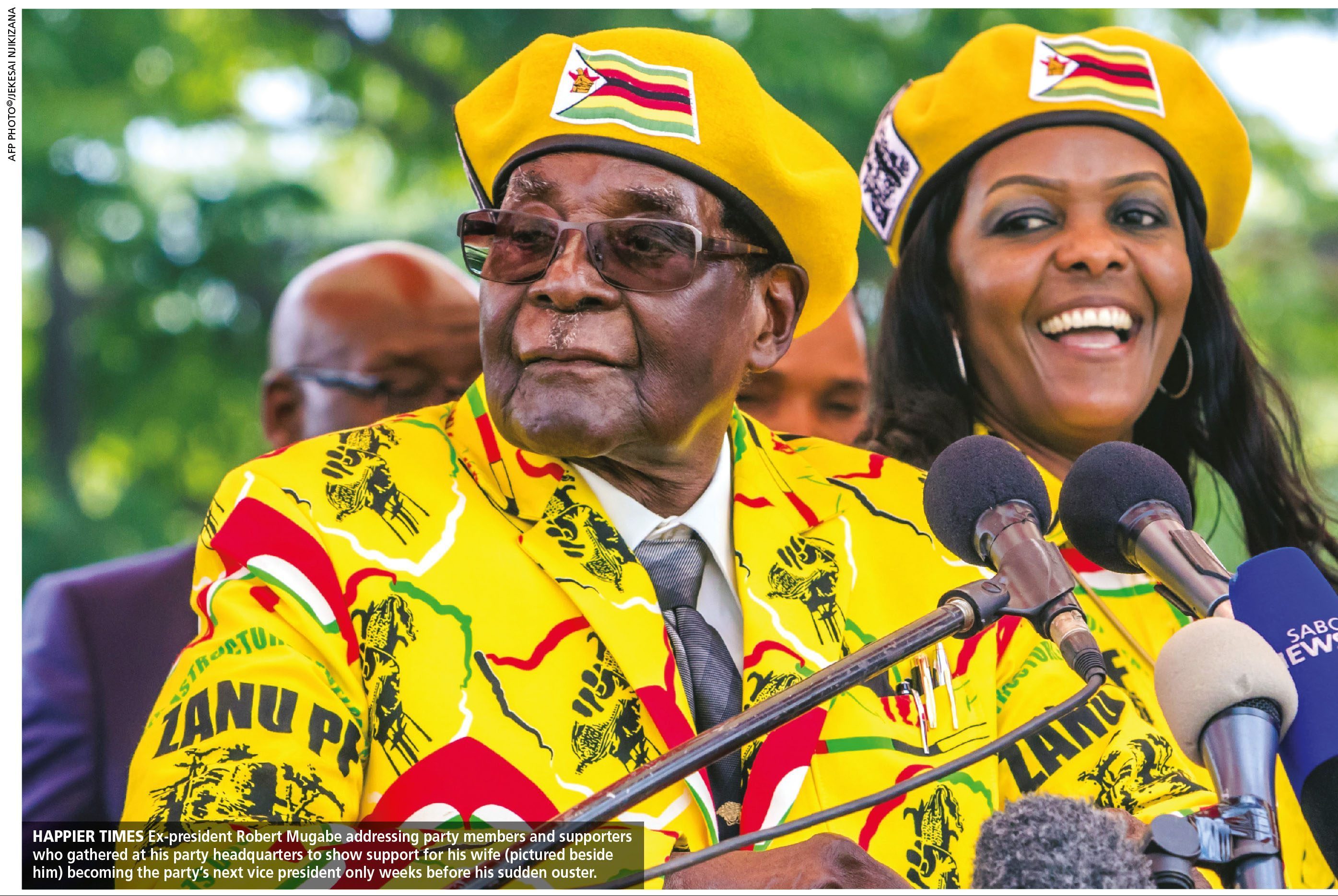

Amantha Perera reports on recent events in Zimbabwe as the Mugabes are sent home

Sandton in Johannesburg is famous for its affluent residents. The large mansions and even many regular houses have electrical wires that run on top of 10 feet high walls. Some say this is the richest mile in Africa – and indeed, it could very well be.

It is here that the family of recently deposed Zimbabwean strongman Robert Gabriel Mugabe loved to hang out. Around three months before Mugabe was unceremoniously dumped by his own party, his wife Grace stormed into a room at a swanky hotel in Sandton where her sons were and assaulted a model. Grace Mugabe was able to leave South Africa because she was granted diplomatic immunity.

The arrogance of the attack was interpreted by many as the extent to which the power of 93-year-old Mugabe had been usurped by his wife who is almost 40 years his junior.

She was using his powers and privileges to the extreme. In fact, the murmurs in Harare and Johannesburg were that she’d appropriated state properties, businesses and even dairy farms from white farmers, by using her husband’s position and wealth.

Grace loved to tell her supporters that the family wasn’t rich but facts proved to be stubborn. In January last year, a judge in Harare ordered her to return three properties she had seized from a Lebanese businessman when a deal on a diamond ring worth US$ 1.3 million headed south.

It seems as if most Zimbabweans didn’t mind the Mugabes becoming richer – in all likelihood, they didn’t have a choice. And if Grace had replaced her husband as head of state, the family would have continued to accumulate wealth and assume even more power.

Many have tried to portray the recent events in Zimbabwe as democratic forces doing away with a despot at long last. But from what I heard in Johannesburg while the drama was unfolding, this isn’t what really happened.

What transpired was a fight between two groups that had been wining and dining at Mugabe’s table – his contemporaries from the freedom struggle and a new group that was orbiting around Grace and known as the ‘G40 faction.’

Grace had a very different beginning to her life before becoming the president’s second wife. Mugabe first met her when she was part of his typing staff while his first wife was very ill. Soon after their marriage in 1996, Grace became known for her extravagant shopping excursions, which earned her the moniker ‘Gucci Grace.’

But as the ageing Mugabe began to fade, Grace became more powerful. She eyed the presidency, which is when things began to heat up. In line to replace Mugabe was his longstanding vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa, and their association goes back to the duo’s struggle to rid the African nation of British colonialists.

Grace and Mnangagwa were on a collision course and in the last few months, they collided. In early November, Grace was heckled at a rally when she spoke and Robert Mugabe blamed the heckling on Mnangagwa’s supporters. As Grace spoke, some in the audience sang in their native language with the lyrics ‘we hate what you are doing.’

That incident took place on 10 November and two days later, Mugabe sacked Mnangagwa. Five days later, Robert and Grace Mugabe were placed under house arrest.

Meanwhile, Mnangagwa had fled to South Africa saying he’d survived an assassination plot, which was traced back to poisoned ice cream from a dairy farm owned by the Mugabes. It was after the sacking that the military intervened and placed the Mugabes under house arrest. Mugabe held on for a week and gave a rambling speech on TV but eventually relented.

Many in Johannesburg are of the view that none of this would have been possible without the tacit approval of South Africa. In fact, when Mugabe met with the military leadership that led the coup for the first time after being ousted, two representatives from South Africa were present.

So now that 75-year-old Mnangagwa has been sworn in as president, will democracy flourish in the impoverished nation?

The direction that Zimbabwe will take isn’t clear. Better known as ‘the crocodile,’ a nom de guerre he acquired during the liberation struggle, Mnangagwa has served as Minister of Defense and spy chief in Mugabe’s regime.

He was also responsible for a violent campaign during the 2008 elections when Mugabe was seriously challenged, and many feel that the latter would have lost the run off if not for mass scale intimidation. The Crocodile’s credentials are no better than those of the man he replaced.

While Zimbabwe’s new president has promised elections next year, there’s no guarantee that he will allow the opposition to regroup. Furthermore, he stands to gain from the goodwill and momentum created by the ouster of Mugabe. His tenure is unlikely to be tense at least

in the short term.

Mnangagwa has solid contacts and firm support among the armed forces as witnessed by the coup. He also has strong links to the regional powerhouse South Africa from where he monitored the coup. And he maintains close links with China, which has been investing heavily in Zimbabwe.

A little known fact is that General Constantino Guveya Chiwenga, head of the defence forces, was on his way to China when Mnangagwa was sacked. It was he who led the coup upon his return to Zimbabwe.

All in all, Zimbabwe will make news for a while – and on the sidelines, its cricketers may make a comeback in the international arena.

A good article. Thank you.

The Mugabes have taught corrupt politicians a good lesson!