FEATURE

THE BUILDING OF A ‘NEW’ IDENTITY

MANDAPAMS OF JAFFNA TEMPLES

A lecture by Dr. T. Sanaathanan and

The National Trust Sri Lanka

BY Archt. Tarita Nugaduwa

Jaffna has always been, in certain ways or by certain people, considered an extension of South India in terms of culture and even lifestyle. As in South India, a majority of those in the north of Sri Lanka identify as Hindus and follow the denomination of Shaivism, which has had a continuous history from the early period of settlers from India.

Culturally, the north of Sri Lanka shares many similarities with the south of India – from religious practices and cultural traditions, to art and architecture; and more specifically, religious architecture.

There are two predominant styles of Hindu temple architecture: Nagara (Northern India) and Dravidian (Southern India), of which the latter has had great influence in Sri Lanka with the greatest influence coming from the Chola period.

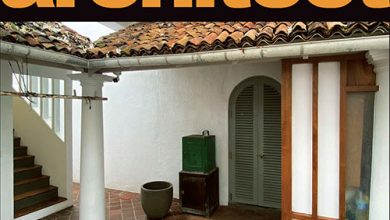

In traditional Dravidian architecture, a temple consists of the mandapa, a pillared hall leading through the gateway (gopuram) into the sanctum; the gate pyramids or gopuras, which are the principal features in the quadrangular enclosures that surround the more notable temples; and the pillared halls (choultries or chawadis), which are used for many purposes and serve as the invariable accompaniments of these temples. Jaffna mandapams (inner worship chambers) in particular underwent significant changes over the past few centuries, reflecting the sociocultural upheaval and varying external influences experienced by the northern community.

Customarily, Hindu temple architecture reflects a blend of expressions, the beliefs of Dharma, values and the way of life cherished under Hinduism. Be that as it may, the Hindu culture has encouraged aesthetic autonomy among its temple builders. The temples were built by guilds of craftsmen, artisans and architects. Their knowledge was initially preserved and passed on verbally and later via written manuscripts. These building traditions were kept exclusively within families, transferred from one generation to the next and this information was jealously guarded.

Although the history of the north dates back thousands of years, reaching the height of its power in the 13th and 14th centuries under the Jaffna kingdom, very little from that time remains today. There were many Hindu temples within the Jaffna kingdom. Some were of great historic importance such as the Koneswaram Kovil in Trincomalee, Ketheeswaram temple in Mannar and Naguleswaram temple in Keerimalai along with hundreds of other temples that were scattered throughout the region.

The occupation of Jaffna by the Portuguese in the 1600s brought about the first major interruption in Tamil culture and heritage. The destruction of ancient temples and palaces, and implementation of a religious ban in an attempt to enforce Catholicism resulted in a major shift in cultural identity, possibly the first blow severing the direct cultural ties between the north of Sri Lanka and South India. This perhaps can be considered the beginning of the history of Jaffna Shiva temple architecture.

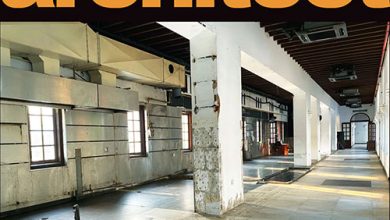

The religious ban on Hindu customs continued during Dutch rule but was lifted in 1778, allowing the construction of a Shiva temple in the vicinity of the Dutch Fort. However, the architecture that emerged at this point displayed very little of its former Dravidian characteristics. The ban that lasted nearly two centuries and destruction of precolonial architecture almost entirely erased the memory of Hindu customs and culture.

The local builders who lost their knowledge of traditional temple building gave shape to these new temples utilising their familiarity with colonial Christian taste, architectural characteristics and building materials. This new style of Hindu temple architecture showcased elements that were heavily borrowed from colonial church architecture with Gothic arches, Doric columns and bell towers. Hence, the evidential architectural history of the Jaffna temple is traceable back to 1778.

Gradually, this style of architecture too evolved with the move towards independence. The reimplementation of Dravidian elements, starting with structures that have more ritualistic importance (such as the gopuram and mandapa), conveys the social shift that was taking place at the time, and can be interpreted as a means of decolonising the art and architecture of Jaffna.

South Indian temple builders were hired for this purpose while the locals were employed for building other outer structures in this process, thus giving birth to a new hybrid style of Hindu temple architecture. This style of architecture remained consistent throughout the early decades of the 20th century until the end of the 1970s, which saw two significant changes –one being the introduction of the free market economy under the presidency of J. R. Jayewardene, and the second being the boiling point of growing ethnic tensions resulting in the beginnings of the Tamil militancy as a response to prolonged minority grievances and marginalisation.

The free market economy enabled more upward social mobility and newfound capitalist values began to blur the lines of the caste system. From this emerged the so-called ‘new rich’ who competed with each other in investing in temples, temple building and temple festivals. During this time, many temples added gopurams and Dravidian style entrance halls at the eastern entrances, replacing the previous Doric styled mandapams.

These radical changes were undertaken by South Indian craftsmen who were highly skilled and familiar with the Dravidian order, formalising the new architectural language. However, this process of development took a different route when the now famous Nallur Kandaswamy Temple removed its Doric pillars and entrance hall to build the present one. The iconic entrance of the Nallur Kandaswamy Temple was designed and constructed by the then trustee of the temple, the late Kumaradas Maapana Mudaliyar, in 1970. Although the orthodox elites originally levelled criticism against his traditional identity, today it has become the desired form of Shiva and Vaishnava temples all over Sri Lanka, varying from roadside to larger temples.

Dr. T. Sanaathanan argues that this architectural style evolved from the impermanent wedding structures known as pandals. In Jaffna, vernacular architectural design tends to evolve over time through the success and failures of experiments, relying on the design skills and traditions of local builders. Therefore, it is closely linked to the cultural material, and climatic, technological, economic and historical context in which it exists, much like the early Hindu temple architecture of India.

Prior to the 1980s, the ceilings of the pandals were covered in white cloth to create a sense of purity within the space. These ceilings were further dramatised with curvatures known as villu or receding steps known as sokattans by stretching the cloth over the framework made from areca nut palm ribs.

“The edges of the steps or curvature were decorated with cloth frills and colonial bell jar lanterns or chandeliers to create an extravagant appearance. Further, these white ceilings were lavishly decorated with glittering gold and silver paper cuttings of geometric design,” Sanaathanan explains.

The shift to lavish aesthetics was perhaps influenced by actual palaces in South India, popularised by film and theatre at the time. The styles of these palaces were a mix of Mughal Hindu and European architectural elements with arches and colonnades. Palace imagery also appeared in the background of religious popular prints on calendars, signifying a cultural shift embracing a long suppressed heritage, possibly fuelled by more open access to South Indian films and pop culture at the time.

With the open economy came the availability of modern construction materials such as steel, which replaced traditional materials. Individuals and cooperative societies took over the pandal service as a new means of generating revenue. The change in social dynamics had a significant impact on the appearance of pandals – decorations that were formally spartan and represented purity were replaced with vibrant, multicoloured aesthetics.

“The ceilings were lavishly decorated with multicoloured cloth frills and lanterns embroidered with glass beads and sequins,” Sanaathanan notes.

These new developments gained widespread popularity, becoming a staple feature in wedding pandals, much to the chagrin of the orthodox elite.

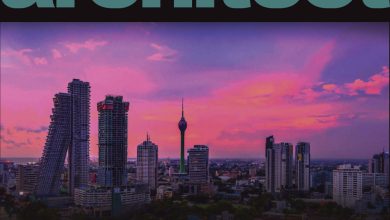

The architecture of the entrance hall of the Nallur temple is a physical translation of Jaffna’s wedding pandals of the 1970s and ’80s. The introduction of concrete allowed the Nallur temple to transform the temporary structures into a more permanent entrance hall, establishing a new trend in temple architecture in the north. The popularity of the Nallur temple contributed to the spread of this style. The monthlong annual festival also contributed to its growth from a village temple into an internationally popular temple. In addition to this, the government published stamps and picture postcards with the image of the Nallur temple, and popularised it as a main cultural attraction of Sri Lanka and the face of Jaffna.

This new style of architecture challenged the belief that northern culture was inextricably linked to the Dravidian culture of South India. Despite heavy criticism, this was perhaps the first step towards establishing a new identity in the north that was relatively independent of external influences. In the 1990s, the government imposed an economic embargo on Jaffna as it was under the control of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the closure of the land route to Jaffna brought a complete halt to the building activities. The creation of high security zones in the north in Jaffna and the exodus in 1995 uprooted thousands of people from their ancestral villages. The formation of internally displaced communities and diaspora drastically altered the traditional social fabric. This not only affected caste and class-based traditional demographics and relationships but also created a shortage of skills.

In the latter part of the ’90s, some temples received a certain amount of compensation for reconstruction. The highly securitised and restrictive environment of the north during this time, with heavy surveillance on artistic expression and a lack of access to entertainment, gave rise to the popularity and heightened importance of temple festivities. In a time of constant instability and uncertainty, temple rituals became the main source of healing from war related trauma. These developments re-accelerated temple architectural projects in the latter part of the 1990s. What emerged during this time was a kaleidoscopic culture of classical folk and popular elements. These clashing identities were merged to form a new aesthetic that cannot be labelled or categorised.

After the end of the armed struggle in 2009, the presence of the Indian sabapathy grew in Jaffna and rather than distancing themselves from the villu mandapam as a non-agamic element, they incorporated it within their stock of skills and knowledge as a business strategy. Sanaathanan says: “Dravidian temples are best understood as perpetually incomplete structures in the process of expanding and contracting in relation to concentric forms built around the particular centre.”

Hindu temple architecture is characterised by its lively tradition of innovation and improvisation. However, there are several entities seeking to standardise and traditionalise architectural forms, and the current architectural language teeters on the fine line of balancing traditional expectations and popular taste based on the ever-changing socioeconomic backdrop.

The lecture notes the silence in the architectural discourse about the marginalised practice of contemporary Hindu architecture in Sri Lanka. The general attitude towards modern temple architecture designed by traditional builders is that it’s kitsch, superficial and a poor imitation of ancient architecture. There appears to be a tendency of architectural historians, professional architects and critics to see contemporary trends of sacred architecture as culturally irrelevant. They are considered to be stuck in limbo, neither conforming to modernist traditions practised by trained architects nor matching up with classical principles followed by their historic predecessors.

What is spoken little of however, is the fact that this popular yet so-called ‘kitsch’ movement is in certain ways undoing the boundaries set by the colonial mindset, and opening up avenues towards a new identity that truly represents a community that has been marginalised for far too long.

PHOTOGRAPHY

https://www.nurphoto.com/gallery/202392/masonry

https://nexttravelsrilanka.com/nallur-kandaswamy-hindu-temple/

https://chulie.wordpress.com/2013/04/27/nallur-kandaswamy-temple-jaffna/

https://www.facebook.com/p/Ampikai-panthal-service100064263212273/?_rdr

RESOURCES

https://www.nurphoto.com/gallery/202392/masonry

https://nexttravelsrilanka.com/nallur-kandaswamy-hindu-temple/

https://chulie.wordpress.com/2013/04/27/nallur-kandaswamy-temple-jaffna/

https://www.facebook.com/p/Ampikai-panthal-service-100064263212273/?_rdr