A PEEK AT THE PAST REMINISCING ON THE FLAMBOYANT LIFE JOURNEY OF TILAK SAMARAWICKREMA

BY Architect Danya Udukumbure

The year was 1973. A young man in his early twenties took his eyes off the sketchbook and looked out of his third floor window to the streets below. Rione Monti, an ancient residential neighbourhood once called the Suburra, was buzzing with its usual activity.

Now a neighbourhood of simple working-class people such as artists, craftsmen and even prostitutes, it always carried the ambience of a theatre with its fabulous ancient architecture, and its little bakeries, restaurants, churches and market places.

Its charming cobblestone paved narrow alleyways were lined with honey coloured low-rise buildings. These alleyways would suddenly open up into a small piazza – an open square, usually with a beautiful fountain in the middle surrounded by bars or cafes where people sat around enjoying the Italian way of life!

The Suburra was the first suburban village of ancient Rome, located on the Palatine with close proximity to the Colosseum. This district, today corresponding to the area of the Monti district, was a maze of alleys, shops and houses, inhabited by gladiators, artisans, prostitutes and plebeian families – commoners of ancient Rome.

It was home to an urban underclass who lived in miserable conditions while also operating as a pleasure district. The term ‘Suburra’ has remained in the Italian language with the generic meaning of ‘disreputable place’ or ‘place of ill repute.’

Gradually, the area was gentrified and changed in character with wealthier people moving in and improved housing, and by attracting new businesses.

Such was the setting where almost a decade of young Tilak Samarawickrema’s formative years were spent. He came to Italy in 1971 on an Italian government scholarship. Samarawickrema was from the third batch of architecture of the Katubedda campus – now known as the University of Moratuwa. The course lasted three years with a three month break each year.

During his time at Katubedda, Samarawickrema spent most of his time in the library, studying international art and artists such as impressionism, Picasso and so on, as well as the work of Ananda Coomaraswamy. Thus, he was well versed in our own art and culture, as well as international styles – the fusion of which was starkly displayed in his work in the ensuing years.

By making his acquaintance with Anura Ratnavibhushana, who was a shining student from the first batch at Katubedda, Samarawickrema was introduced to Geoffrey Bawa. By showing Bawa his work, he then got the opportunity to work with him at Edwards, Reid and Begg during the three month break across all three years of the course.

It was a period of postcolonial renaissance in terms of art, architecture and culture in Sri Lanka, ignited by the likes of Bawa, Ena de Silva, Barbara Sansoni and Laki Senanayake, who produced a new awareness of indigenous materials, crafts and architecture. They frequented the office where Bawa and Ulrik Plesner worked, which has been converted into the Gallery Café.

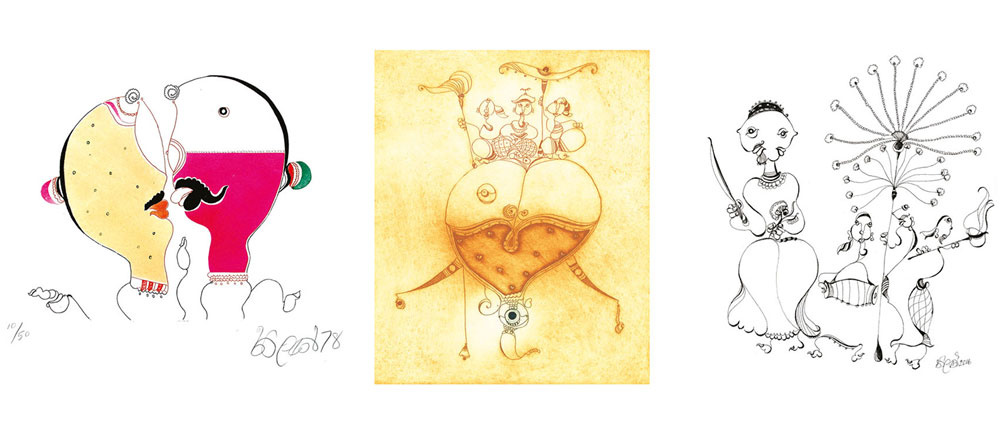

Here, young Tilak Samarawickrema had a lot of free time where he began the habit of doodling. All sorts of perplexing thoughts and emotions in his young mind started to flow through his Rapidograph pen and turned into a form of line drawings, which he suddenly realised weren’t mere doodles but his very own unique style of drawing.

His sensual curling lines, thickening and thinning, being plain and detailed as the rhythm requires, almost resembles Sinhala calligraphy. Consequently, Tilak Samarawickrema gifted the world a new art form that was contemporary but Sri Lankan in spirit.

It tells rich stories of predominantly Sri Lankan culture, traditions and activities of daily life, giving form and animation to stories in an expressive, harmonious and skilful manner. Before leaving for Italy, he managed to hold his very first art exhibition in Colombo.

While most of his contemporaries moved on to England, America or Australia for further studies, Samarawickrema was the only one who went to Italy. That made him and his work remarkably different to the rest when they returned.

This was a time long before the internet and he had no knowledge of Italy except for two influences he had before obtaining the scholarship. The first was from Roland Silva who had just returned to Sri Lanka and was his history lecturer. He had tasked his students with conducting a comparative study of the Greek agora and Roman Forum.

The second was a book he read by Alberto Moravia (1907-90) – a famous Italian novelist who is best known for his debut novel Gli Indifferenti (The Time of Indifference, 1929) and the antifascist novel Il Conformista (The Conformist, 1947), which was the basis for the film The Conformist (1970), directed by Bernardo Bertolucci.

His writing was rooted in the tradition of the 19th century narrative, underpinned by high social and cultural awareness, and his depiction of relationships, sexuality and the sensuality of women fascinated Samarawickrema.

Thus, he embarked on a journey to Italy, not knowing that this was going to completely alter the trajectory of his life’s direction by opening a world of opportunities and recognition that would ultimately raise him to a platform where he would become an internationally renowned artist and architect. For the first two years, he was at the Polytechnic University of Milan, the largest technical university in Italy.

Italy is recognised as being a worldwide trendsetter and leader in design: Milan is recognised internationally as one of the world’s most important fashion capitals, along with Paris, New York and London.

In the early 1970s, several design movements were taking place in Europe, reflecting the changing cultural and social landscape of the time. Some of the prominent design movements during this period include postmodernism, the Memphis Group, Bauhaus influence, Italian Radical Design, anti-design and punk aesthetics.

Samarawickrema arrived at the height of the Italian Radical Design period. It used new materials and bold colours, much like pop art did while also drawing inspiration from historical styles such as art deco, kitsch and surrealism, while at the same time questioning modernist design and architecture.

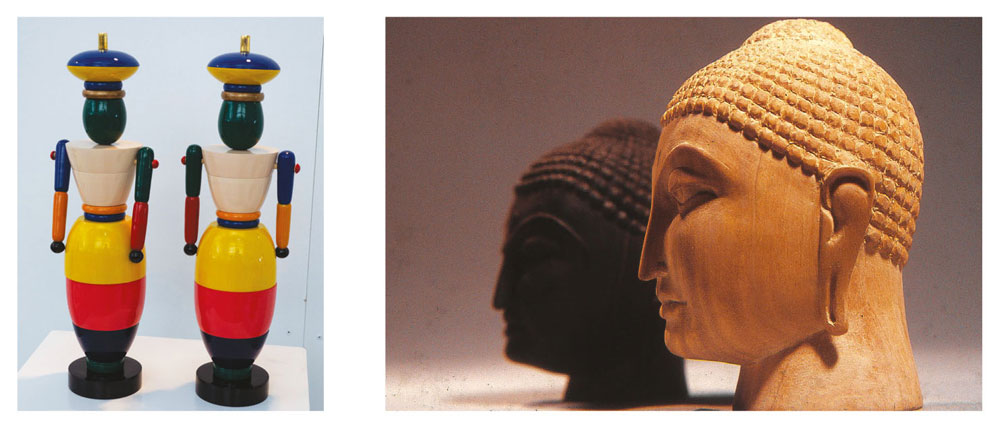

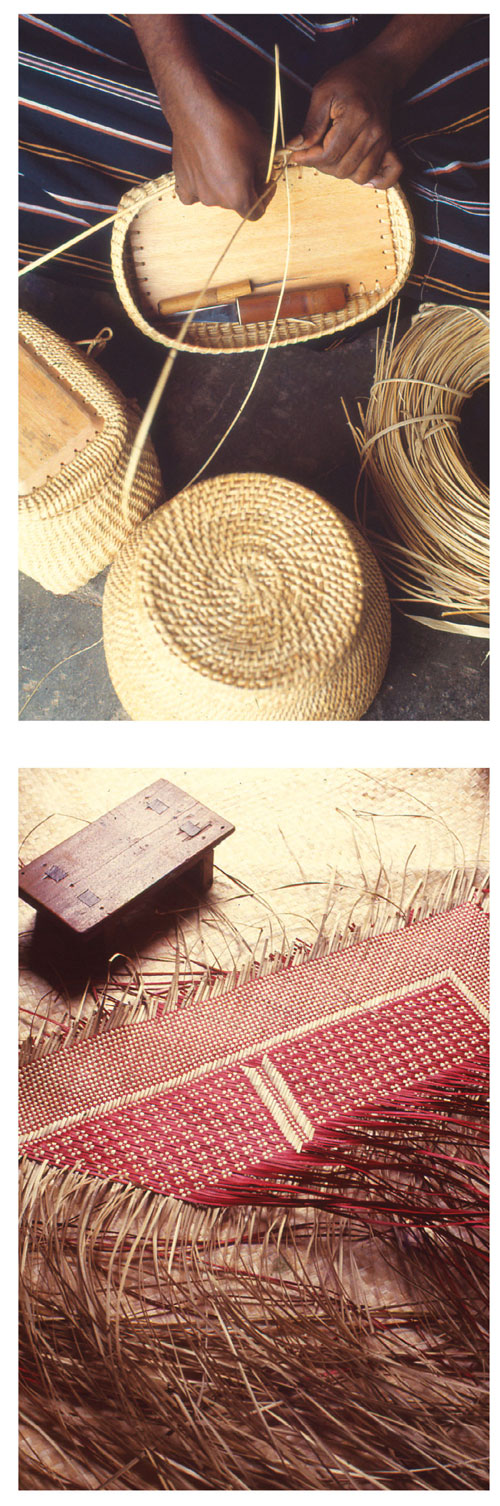

The Bauhaus influence on Samarawickrema was vividly evident in his work in the arts and crafts when he was appointed Design Consultant to the National Design Centre (NDC) of Sri Lanka on an ILO assignment in 1986.

His task was to establish a design unit in the NDC and execute a rapid craft development programme. With his design team, Samarawickrema travelled far and wide, scouring the countryside for skilled artisans and found them in little pockets of villages scattered across the country.

The fruits of this labour culminated in the inaugural Shilpa exhibition held in 1987, which then became an annual event organised by the Ministry of Traditional Industries and Small Enterprise Development. This was arguably a turning point in the Sri Lankan arts and crafts field where the local craftsmanship was infused with modern design sense, reuniting art and craft to arrive at high-end functional products with artistic merit.

The Memphis Group was a highly influential design movement that emerged in the early 1980s, named after the Bob Dylan song Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again. It was known for its avant-garde and unconventional approach to design and explored a visual language outside of the limiting canons of ‘good taste,’ blurring the boundaries between ‘high culture’ and mass produced ‘ordinary’ consumer goods.

It rejected the minimalist and functionalist principles of modernism and instead, embraced bold, colourful and often whimsical designs, and had a sense of humour that was lacking in design at the time.

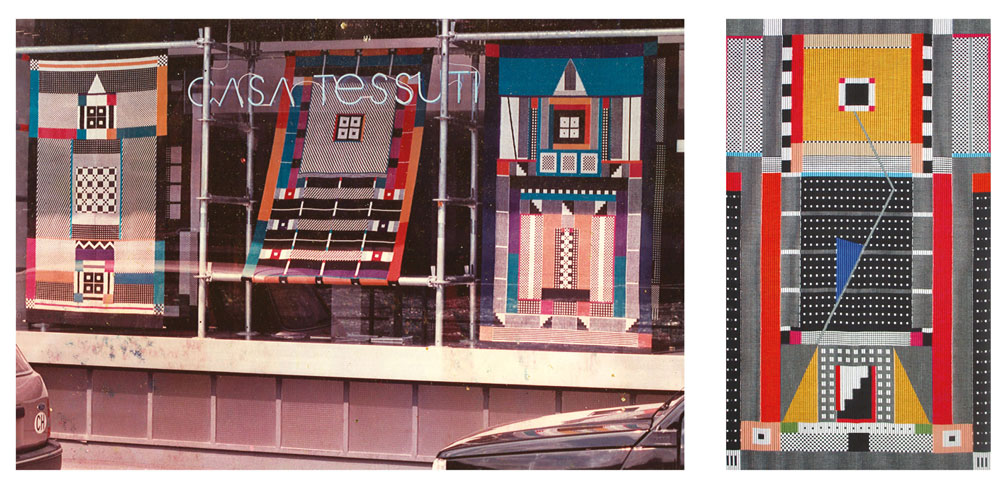

One can easily draw parallels between the characteristics and features of Memphis design and the work of Tilak Samarawickrema – especially in his tapestry designs. Vibrant colours, geometric shapes, pattern and graphics, playfulness and irony, and the blending of influences created a unique and eclectic design language.

With this approach in 1990, Samarawickrema revolutionised the works of the traditional weavers of Talagune and Udadumbara in place of the traditional repetitive design motifs.

Subsequently, the works of the humble weavers of Talagune – who from time immemorial provided cloth to kings and feudal chieftains – travelled to the SHED design gallery in Milan (1992); Norsk Form, a design museum in Oslo (1998); Casa Tessuti (1992); Schweizer Galerie (1993) in Switzerland; Galerie Smend and Deutsches Textilmuseum in Germany (1994-95); and MoMA Design Store in New York (1992-2000) to name a few.

Samarawickrema’s stay in Milan didn’t last longer than two years. The influence of what is known as May 68 – a series of events that took place in France in May 1968 – was catching up to Milan and the rest of Europe. It was a period of intense social and political upheaval, characterised by student protests, labour strikes and widespread civil unrest. As a result, the Polytechnic was indefinitely closed due to strikes, which prompted him to move to Rome.

This period contributed to the development of progressive and liberal attitudes, particularly among the younger generation.

It may be fate that a multifaceted artistic genius with a rich cultural heritage found himself in the thick of a cultural transformation in Europe that was a significant moment in 20th century history.

Samarawickrema’s creative alchemy had the ability to absorb the richness and spirit of his land, and infuse it with the fresh and contemporary global trends, and produce many different art forms that were truly unique. His creative ability – especially the sensuality of his line drawings – ignited the interest of the Italian art world, drawing the attention of and establishing close acquaintances with significant personalities of the time.

In 1974, his animated film out of his line drawings – Andare of Sri Lanka – was presented at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen as an Italian entry. He then managed to invite Moravia to a private screening of the film and was delighted when he obliged. Moravia found the animated line drawings sensual and erotic.

His friendships with renowned architects Angelo Mangiarotti and Franco Mirenzi had a pivotal impact on his time in Italy. Mangiarotti introduced him to Bruno Munari, an acclaimed Italian artist, designer and inventor who contributed fundamentals to many fields of visual arts. He is termed as ‘one of the greatest actors of 20th century art, design and graphics.’

Through Munari, Samarawickrema grew his network of friends in the design industry, which opened up further avenues of opportunities.

Pierre Restany – an internationally known French art critic and cultural philosopher – was fascinated by his work and wrote many introductions to Samarawickrema’s books and exhibition catalogues.

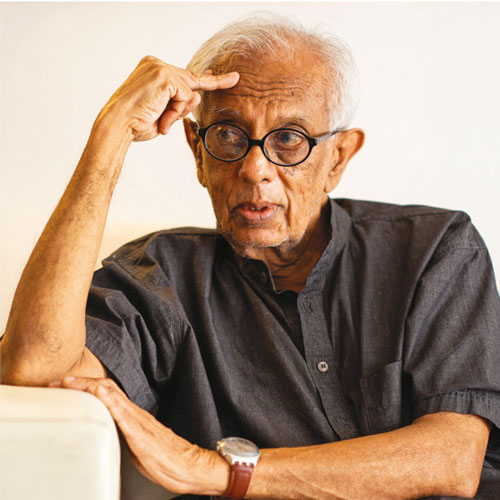

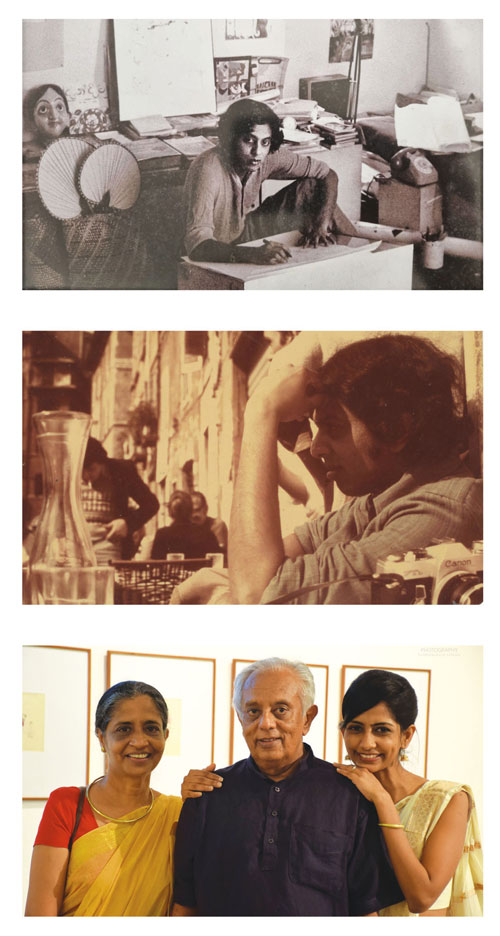

Sitting across from me in his beautiful gallery-like home at Ascot Avenue, Samarawickrema’s face lights up with quirky smiles as he relates his adventures from a time long ago. His is a long and fulfilling life that has put Sri Lanka on the world design map.

His personality is as vibrant and colourful as his plethora of work. His sharp, matter of fact countenance and flashes of elitist arrogance might keep a lot of people at bay but to those who have been fortunate to know him, he is a warm, kind and affectionate individual with a great sense of humour. His spirited, amusing conversations and hearty laughs only prove that his youthful exuberance is timeless.

RESOURCES

In conversation with Architect Tilak Samarawickrema

PHOTOGRAPHY

Architect Kasun Wickremage

Architect Tilak Samarawickrema – archives