ENTREPRENEURSHIP

When it comes to entrepreneurship and economic policy, certain conditions – such as a stimulating environment for new businesses and start-ups, financial incentives, incubators or co-working spaces and restructuring of educational syllabi to promote entrepreneurship – are considered prerequisites.

When it comes to entrepreneurship and economic policy, certain conditions – such as a stimulating environment for new businesses and start-ups, financial incentives, incubators or co-working spaces and restructuring of educational syllabi to promote entrepreneurship – are considered prerequisites.

START-UPS AN OBSTACLE COURSE?

Gloria Spittel highlights the challenges and prospects for entrepreneurship in Sri Lanka

However, new research suggests that the number of start-ups and new businesses does not indicate economic growth, tax exemptions may lead to bad investments, and there is no causality between incubators and entrepreneurship-focussed education and increased entrepreneurial business.

Yet, how can entrepreneurship – which is acknowledged as the driver of future economic growth in advanced, emerging and least-developed countries – be fostered?

Regardless of the concept’s definitional base of rising above the lack of resources, the private sector and NGOs could add additional support to the efforts led by governments.

So where do the state, private and NGO sectors begin?

Four criteria assist in the development of an entrepreneurial culture: access to talent, reduced bureaucracy, a viable customer base and early-stage funding. In Sri Lanka, some of these are both a challenge and a prospect, while others are obstacles to entrepreneurship.

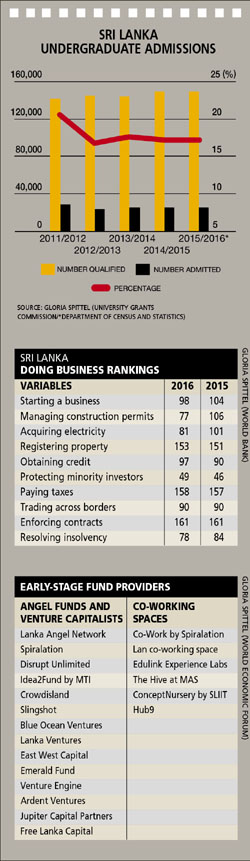

This year, Sri Lanka’s ranking in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index improved marginally – from 113 last year, to 107, of 189 countries surveyed. The index is a composite measure of 10 variables that include launching a business, enforcing contracts, paying taxes and obtaining credit.

Currently, there are eight procedures involved in launching a business that would take a median 10 days to complete. In contrast, starting a business in Singapore (ranked first in the index) consists of three procedures and a median of 2.5 days.

Early-stage funding is a crucial issue for entrepreneurs across the globe. In Sri Lanka, in a study conducted by Sri Lanka Association of Software and Services Companies (SLASSCOM), entrepreneurs placed ‘access to debt capital from banks’ as the third-largest obstacle to start-up growth, while availability of capital was ranked first as an enabler of start-up success. Sixty-two percent of the entrepreneurs also resorted to either personal savings, or family and friends, for funding.

Early-stage funding is a crucial issue for entrepreneurs across the globe. In Sri Lanka, in a study conducted by Sri Lanka Association of Software and Services Companies (SLASSCOM), entrepreneurs placed ‘access to debt capital from banks’ as the third-largest obstacle to start-up growth, while availability of capital was ranked first as an enabler of start-up success. Sixty-two percent of the entrepreneurs also resorted to either personal savings, or family and friends, for funding.

While entrepreneurs are not spoilt for choice when it comes to financing, there are options available – for example, Blue Ocean Ventures, Disrupted Unlimited, Lanka Ventures, Spiralation and Crowdisland.

Developing a viable customer base should not be mistaken for the development of a middle class. While a thriving middle class is certainly a goal, it cannot – and should not – be the only goal. There are prospects or opportunities hidden among the rural and urban poor people that make up a substantial base to which entrepreneurs can turn, as either a market for their innovative and socially responsible products, or a base from which to derive talent.

Access to talent is presumably the most important criteria. Rather than thinking of talent as a subjective and intangible individualistic character trait, there should be a conscious approach to the development of talent as an objective measure. This centres on the competencies and offerings of the educational and vocational training institutes spread across the country.

Sri Lanka’s literacy rate and secondary school enrolment figures are generally applauded. While these are achievements, in the context of the island’s war-torn history and economic development, they’re also the prospective building blocks on which talent for entrepreneurship can be built.

Turning to tertiary education, the numbers are confounding, and government funding is both staggered and insufficient. The situation is drastically worse for individuals who opt to pay shady institutes, to obtain degrees or international qualifications. While the paper qualification may come through for an exorbitant price, there are no clear procedures to prevent the operating and preying of degree mills on desperate students.

There is no dearth of desperate students. In 2014, of the 247,376 students who completed the local A-Level examination, 60 percent were eligible to enter the 15 universities spread across the island. However, only 17 percent (25,676 students) were granted admission in academic year 2015/16. The student population across universities, institutes and open universities last year numbered 109,182.

The low admission rate poses two problems: firstly, it is doubly harder to harness the ever-changing workforce skills; and secondly, the shortage of skills renders the labour force unattractive, which may lead to recruitment from outside Sri Lanka, resulting in a spiralling and ugly domino effect.

Of course, to right these wrongs, the structure of tertiary education necessitates that government has to introduce beneficial and future-oriented policies. On the flip side, the private sector and NGOs that have identified the basic skills needed, can develop train-to-hire programmes. While this does happen, it is not a widespread remedy to nurture entrepreneurial excellence.

Entrepreneurship is the way forward, even though its rosy healthiness is puckered by obstacles. But in that all too familiar national pastime of bypassing obstacles, these hurdles can be overcome.