It’s the Economy, Stupid

Dr. Howard Nicholas is a distinguished economist whose extensive career has been marked by a relentless pursuit of knowledge and an impact on the world of economics. For over four decades, he has been at the forefront of teaching economic development, business economics and financial markets.

Dr. Howard Nicholas is a distinguished economist whose extensive career has been marked by a relentless pursuit of knowledge and an impact on the world of economics. For over four decades, he has been at the forefront of teaching economic development, business economics and financial markets.

Nicholas has taught these subjects at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) – part of Erasmus University of Rotterdam – where he earned accolades as an exceptional educator, consistently winning the best teacher award for his outstanding contributions to learning.

His commitment to excellence transcends borders as he shares a wealth of knowledge with students across the globe, teaching at business schools in a number of countries including Sri Lanka, China and Vietnam.

Beyond the classroom, Nicholas’ foresight and analytical insights have earned him widespread recognition. His timely warnings on economic crises – from the Asian crisis of 1997 to the global crises of 2001, 2007/08 and 2020 – solidified his reputation in the field.

As a senior trainer at Economic Training & Information Services (ETIS) Lanka, he continues to mentor future generations of economists across the world.

Prior to founding ETIS Lanka, Nicholas played instrumental roles in various ventures – notably in 1989, when the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) was established.

Between 1987 and 2001, he played a pivotal role in advancing graduate studies at the Department of Economics, University of Colombo. And in 1990, Nicholas founded Econsult, an economic advisory firm in Sri Lanka, where he provided strategic guidance and insights to both public and private sector entities.

Furthermore, in the early 2000s, Nicholas established the FHR Lim A Po Institute for Social Studies’ Schools of Business and Governance in Suriname, a Caribbean nation situated north of Brazil. His involvement in this initiative underscores a commitment to expanding economic education in diverse global contexts.

Nicholas’ impact extends far beyond the classroom, as evidenced by his contributions to academic literature with numerous articles published in international journals, and two seminal books on the theory of price with Springer-Macmillan in 2011 and 2023. Presently, Nicholas is crafting two sequels to his 2023 book, slated for release in 2025 and 2026.

– Compiled by Tamara Rebeira

“The rate of inflation may have fallen but incomes of ordinary people have not risen by anything like the increase in the prices of basic food items”

Dr. Howard Nicholas

Q: Sri Lanka’s economy has faced numerous challenges in recent years. How do you view the state of the economy at this time?

A: Sri Lanka is coming out of a foreign exchange crisis with the aid of the IMF, and various other multilateral and bilateral donors.

There are no power cuts and petrol queues, and inflation has receded from the highs it reached in late 2022. Foreign exchange reserves have risen steadily and the Sri Lankan Rupee has recovered much of the ground it lost during the crisis.

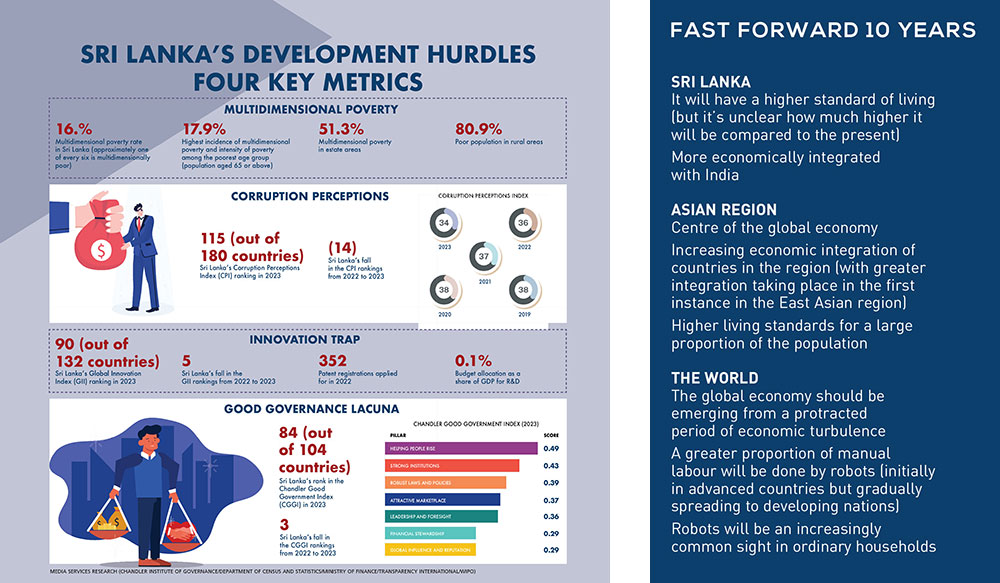

On the downside however, poverty has worsened considerably; many households no longer have access to electricity; there has been an unprecedented exodus of the country’s youth; the recovery in foreign exchange reserves and external value of the rupee should be viewed in the context of continued restrictions on certain high value imports and a moratorium on the servicing of US$ 12 billion in foreign debt; and export levels have not recovered to even their depressed pre-COVID levels.

Q: Privatising state owned entities (SOEs) has been a contentious issue – and it has brought the trade unions onto the streets when it’s discussed. What are the potential advantages and disadvantages of privatisation in the context of the national economy?

A: Sri Lanka is a capitalist economy so it makes sense for the majority of companies to be privately owned and run. This means that there is justification for the privatisation of many SOEs.

However, it makes sense for some caution to be exercised in the privatisation of certain entities such as those involved with energy, water, railways, airports and the like.

This is due to the prices of services provided by SOEs in these sectors having a considerable bearing on the cost of production of most Sri Lankan businesses and living standards of the population at large.

The problem is that many of these enterprises are natural monopolies, providing whoever owns them with monopoly powers to price gouge.

In instances where state run enterprises in such sectors are performing poorly, they must be restructured and not privatised. We have many examples of the negative consequences of privatising state run enterprises in such sectors in advanced countries.

Perhaps the clearest of these are the privatisation of rail services, airports and water in the UK. Even those who once favoured the privatisation of these services in the United Kingdom have expressed regret of this advocacy.

Q: Around a year ago, you stated that considering the past, the IMF’s recommendations have not helped countries like Sri Lanka. Given our extensive efforts to meet the conditions set by the so-called lender of last resort and signs that Sri Lanka may come out of bankruptcy, are you still of the same view?

A: The fact that this is the 17th time Sri Lanka has gone to the International Monetary Fund should be testimony enough that simply adopting its standard deflationary policy recommendations (i.e. reducing the budget deficit) will not result in a sustainable foreign exchange reserve situation over the long run.

The real test of this sustainability will come when the government is forced to liberalise all imports, and begin to repay its foreign debt and interest arrears.

It is perhaps telling that the government has requested a foreign debt moratorium until 2028. In fact, I cannot think of any country that has emerged from an IMF adjustment programme with a sustainable external balance.

This includes Sri Lanka and its 16 prior adjustment programmes with the lender. In its 2023 World Economic Outlook, the IMF acknowledged that “on average, fiscal consolidations do not reduce debt-to-GDP ratios.”

It makes sense for some caution to be exercised in the privatisation of certain entities such as those involved with energy, water, railways, airports and the like

Q: The International Monetary Fund recently stated that Sri Lanka is showing signs of improvement, following its worst economic crisis of two years ago. The IMF’s Mission Chief for Sri Lanka Peter Breuer said that the country’s path is on a “knife edge and could easily go back to a vicious cycle.” How do you view this statement?

A: I think that this statement is designed to do two things.

First, it’s designed to put pressure on Sri Lankan authorities to stick to the agreed programme.

Second, it is designed to give the IMF its standard fallback position when any country it has a programme with returns for further assistance – that the full IMF programme was not implemented by the country concerned on the previous occasion.

Q: Given the ongoing economic and fiscal challenges facing Sri Lanka, what do you see as the most pressing issues that need to be addressed? And how does this being an election year affect the status quo?

A: I see the major economic challenge being Sri Lanka’s protracted trade imbalance. This imbalance has led to the accumulation of foreign debt and recurrent foreign debt servicing problems.

The IMF has blamed excessive budget deficits run by successive Sri Lankan governments for the protracted trade imbalance. Yet, the data shows that while the trend budget deficit fell considerably over a period spanning from the late 1970s to end-2019, it remained stubbornly high over this period.

As I have argued for a very long time, what’s required is the adoption of an aggressive manufacturing-based, export-oriented growth strategy – sometimes referred to as an export-oriented industrialisation strategy. Only countries that have adopted such a strategy have managed to achieve protracted external trade surpluses and avoid recurrent foreign exchange crises.

There are certainly fiscal problems that need addressing. The current focus on raising tax revenue is long overdue. Sri Lanka has had one of the lowest tax revenue bases in the world for a very long time.

However, the manner in which the government has sought to raise tax revenue is exceedingly inequitable.

I believe that this is also the unspoken view of the IMF. What has not been addressed by way of fiscal consolidation, also in the lender’s programme, is the interest component of government expenditure. As a percentage of current government expenditure, this has been among the highest in the world for a very long time.

And I have expressed concern over the recently gazetted Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act. This will most certainly add to interest expenditure pressures as will the encouragement by the IMF for Sri Lanka to return to the international capital markets.

We have already seen the government doing a number of things with an eye on the forthcoming elections. These include reductions in electricity tariffs and fuel prices, some targeted tax relief, liberalisation of food imports, announcing the creation of a national development bank to provide low-cost capital for SMEs and so on.

The rate of inflation may have fallen but incomes of ordinary people have not risen by anything like the increase in the price of basic food items.

In fact, real incomes appear to be where they were during the depth of the crisis. In addition, many low-income earners now find themselves having to pay taxes out of their meagre incomes.

What’s required is the adoption of an aggressive manufacturing-based, export oriented growth strategy

Q: Politicians are hither and thither with concessions ahead of elections, which can undermine investor and business confidence. How do you assess the long-term repercussions of such political manoeuvres on economic stability and growth?

A: What matters for long-term growth and stability, as well as investor confidence, is a profitable business environment.

Such an environment does not come with fiscal stringency; nor is it gravely damaged by pre-election giveaways that are perceived as having a bearing on the latter.

What is damaging to a profitable business environment is the failure of government to adopt an industrialisation strategy and stick to it, irrespective of pressures emanating from the domestic political and external environments.

Q: What strategies do you think would be effective in tackling poverty and the plight of marginalised communities in Sri Lanka – and how can they be implemented?

A: I’m against an excessive reliance on poverty alleviation policies such as cash transfers and the like for tackling poverty.

These policies fail to tackle poverty in a manner that helps marginalised communities to permanently come out of poverty and are frequently used for political patronage.

What’s needed instead are job creation programmes, complemented by the provision of low-cost housing and improved sanitation. The job creation programmes should be geared towards helping individuals develop marketable skills that enable them to acquire progressively higher salaried jobs.

This means that there should be a greater emphasis on what has been referred to in the past as vocational training programmes. The need for such programmes is even greater in a world of rapid and wholesale technological change.

Q: You’ve described the tax cuts and other economic policies implemented by the former administration – such as reducing tax and interest rates, and suspending imports of agrochemicals – as having been disastrous. Do you then approve of the tax regime that came into effect in Sri Lanka this year? Are there any other approaches to establishing an equitable tax regime?

A: As mentioned earlier, the recent increase in tax revenue was much needed but it should have been more equitable.

The burden of the tax increase should have been on individuals earning relatively higher incomes or having a higher value of assets. To achieve this, I would suggest the following.

First, the income tax threshold could have been set at a higher level – e.g. Rs. 150,000 or even 200,000 rupees monthly, instead of Rs. 100,000 – and higher income earning individuals could have been required to pay a relatively larger proportion of their incomes in taxes.

Put simply, the structure of income taxation should have been made more progressive.

Second, expenditure taxes such as value added tax (VAT) are known to be regressive (i.e. resulting in people with lower incomes paying a relatively larger share of their incomes in expenditure taxes compared to high income earners).

Therefore, the imposition and increase in VAT on all consumer goods has had a disproportionately greater impact on lower income households. A more equitable approach would have been to exempt a certain basket of basic consumer items from being subject to VAT.

Q: Bad governance and corruption are often cited as being serious impediments to economic and social development. What measures do you believe are necessary to instil good governance and combat corruption, given the prevailing political landscape?

A: The agreed (with the IMF) transparency and accountability measures are a step in the right direction, provided they’re implemented. It is my understanding that their implementation has been problematic.

I should add that curbing corruption per se is not the panacea it is claimed to be. Simply eliminating corruption – however laudable this may be – isn’t a magic bullet. Economically successful countries (including China and the US) are known to be riddled with corruption.

Moreover, most of the proposed measures target petty corruption, leaving unscathed corruption at the higher levels.

The manner in which the government has sought to raise tax revenue is exceedingly inequitable

Q: Additionally, what are the key priorities that policy makers should focus on to promote sustainable economic growth and drive social development in Sri Lanka?

A: Aside from export-oriented industrialisation, key areas that require the government’s attention are food security, infrastructure development, the promotion of R&D, reform of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act, and closer scrutiny of the various free trade agreements (FTAs) Sri Lanka has entered into and is proposing to sign.

The reduction of subsidies granted to agricultural producers and recent liberalisation of food imports is a step away from food security – i.e. the domestic production of basic food crops for domestic consumption. Food security has been an indispensable ingredient of most successful export-oriented industrialisation strategies.

Infrastructure development and R&D expenditure have been much neglected areas of public policy. One reason for this is the continuous upward pressure exerted on the fiscal deficit by low tax revenues and excessively high interest payments, leaving little or no space for such expenditure.

The experience of all high growth economies – including minnows like Singapore and Hong Kong – show that infrastructure and R&D expenditure are of crucial importance for this growth.

And the recently promulgated Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act is likely to exacerbate upward pressure on both economy-wide interest rates and the exceptionally high level of interest payments by the government.

This act will aggravate the upward pressure by introducing a risk premium on government domestic debt where there was previously none. This risk premium stems from the fact that the act prevents the Central Bank of Sri Lanka from purchasing government debt that isn’t purchased by commercial banks in primary auctions.

Lastly, some attention needs to be paid to the FTAs that Sri Lanka has already signed in order to establish whether they have been beneficial and if not, why they haven’t – with a view to learning from these experiences.

Some attention should also be paid to the recent FTA signed by Sri Lanka with Thailand, which goes well beyond the mere liberalisation of trade in commodities and services.

Of particular note in this regard are the agreements in respect of foreign investment inflows, government procurement and intellectual property rights, as well as the investor to state disputes protocols.

The agreements in respect of foreign investment flows – so-called investment agreements – and government procurement undermine the use of these in the promotion of domestic industries.

And the investor to state disputes protocols could see Sri Lanka faced with costly litigation in the manner of many other countries that have signed similar FTAs to those signed by Sri Lanka with Thailand.

Q: On the debt restructuring front, Sri Lanka is currently seeking a loan moratorium for bilateral debts amounting to 12 billion dollars – including US$ 4.6 billion to China and nearly 1.4 billion dollars to India – until 2028. In addition, our external debt portfolio (US$ 37.3 billion in sum) includes multilateral debtors (10.8 billion dollars) and commercial loans (US$ 14.7 billion). Where do you see the light, if any, at the end of this dark tunnel – and what solutions are there for Sri Lanka to come out of the debt trap it is in?

A: The debt trap that Sri Lanka finds itself in is an international sovereign bond (ISB) debt trap – not a bilateral debt trap.

In fact, a frequently neglected proximate cause of the country’s recent foreign debt crisis was the sharp increase in ISB debt incurred by Sri Lanka during the period between 2015 and 2019 when the incumbent president was the prime minister of the country.

Although ISBs came to account for 36 percent of total foreign debt outstanding on the eve of the crisis, the interest in respect of this ISB debt accounted for over 70 percent of total interest payment owed on foreign debt by Sri Lanka.

One lesson that Sri Lanka should have learned from this experience is the need to avoid incurring similar costly foreign currency denominated commercial debt in the future. Going forward, any such proposed expansion of foreign debt should be made subject to parliamentary oversight.

Perhaps a more fundamental lesson – and one I referred to earlier – is that there’s a need to eliminate the structural imbalance in Sri Lanka’s external trade and current accounts. The recent improvement in the current account balance – i.e. the attainment of a surplus in this balance – is not indicative of the required structural improvement in it.

This improvement is due to the depressed state of economic growth, continued restrictions on imports and the temporary moratorium on debt servicing, which quite simply means that the improvement is not sustainable. It will only become sustainable once there is a structural transformation of the underlying trade balance – i.e. shifting from a trend deficit to a trend surplus.

Am I optimistic that Sri Lanka will emerge from the dark tunnel into the light? Yes.

My optimism comes from having lived through the dark days of the late 1980s in Sri Lanka when there was civil strife in both the northeastern and southern parts of the country, and the economy was in shambles.

Pessimism was rife. Within the space of a few years after the assumption of the presidency by Ranasinghe Premadasa in 1989, the economy had turned around. Foreign investors poured money into the economy and Sri Lanka was even hailed, somewhat prematurely as it turned out, as being the next Asian tiger.

The burden of the tax increase should have been on individuals earning relatively higher incomes or having a higher value of assets