In May 1967, the Constitution of Australia was amended through a referendum and the phrase ‘other than the aboriginal race in any State’ was removed. In fact, the entire section 127 was removed and didn’t refer to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples anywhere else in the constitution.

AUSTRALIAN VOTERS SAY ‘NO’ TO THE VOICE

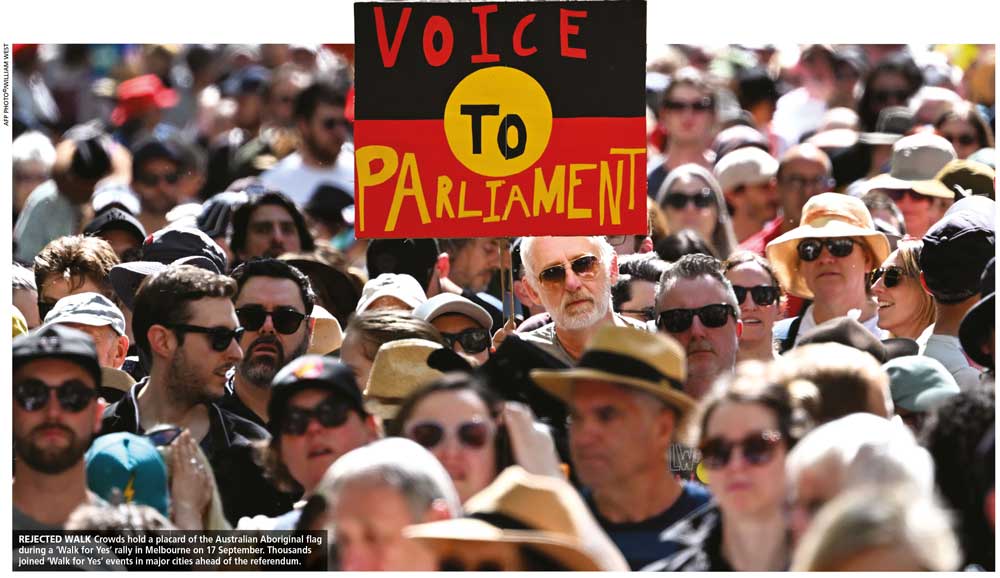

Saro Thiruppathy explains what contributed to the failure of a referendum that would have ensured more inclusivity for the First Nations Peoples

This deletion was apparently done to allow the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to be considered part of Australia’s population, and enable the Commonwealth government to enact laws on their behalf.

However, the amendment did not grant voting rights to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in spite of the fact that in 1962, this had been granted by Commonwealth legislation.

Furthermore, the amended constitution also didn’t recognise the aforementioned populations as the First Peoples of Australia.

Only in 1992 did the High Court overturn the notion of terra nullius, which means unoccupied land prior to colonisation, and recognise the past and continuing relationship that these people have to Australian land.

In 2010, the head of the Labour Party Julia Gillard promised to include the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the constitution. But in the end, she abandoned the idea and reneged on her election promise.

THE REFERENDUM Then in 2022, the leader of the Labour Party Anthony Albanese promised what Gillard did – but through a referendum. And he claimed that recognition would be given through an advisory body known as ‘The Voice.’

Subsequently on 14 October, Australians went to the polls to vote on whether or not the constitution should be changed to recognise the First Peoples of Australia through the establishment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

But the ‘no’ votes spoke louder with 60 percent of the population objecting to any constitutional reforms.

In the referendum, Australians were asked whether they approved of a law to alter the constitution and recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

If approved, a new section would have been inserted in the constitution.

LEGAL CHANGES Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice – In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the First Peoples of Australia.

I There shall be a body, to

be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

II The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples;

III The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

Albanese announced the referendum question and constitutional amendment in March after consulting with the First Nations Referendum Working Group. And in June, the question and amendment details were laid out in the Constitution Alteration Bill, which was passed by both Houses of Parliament on 19 June.

The aim of the government was to ensure that the constitution didn’t discriminate against anyone or give any Australians more rights than others. It was hoped that these factors would build stronger ties of trust and respect between the First Nations Peoples and Australians in general.

THE ‘NO’ CAMPAIGN Opposition Leader Peter Dutton was pleased with the result of the referendum.

He had warned: “Instead of being ‘one,’ we will be divided in spirit and in law.” The ‘no’ campaign’s slogan was simply ‘Divisive Voice’ and though it had no banners or posters, it sat well with the voters.

Another slogan was ‘If you don’t know, vote ‘no’.’ That seemed to make sense to voters since many were unaware of how the process would play out if the referendum was passed.

So the uncertainty coupled with majority fears convinced many to oppose the proposal.

A separate movement led by Aboriginal Senator Lidia Thorpe and the Indigenous Blak Sovereign Movement also voted ‘no’ in the referendum. Her movement wanted a legally binding agreement between the First Nations Peoples and Government of Australia to be a priority.

Thorpe noted: “This is not our constitution. It was developed in 1901 by a bunch of old white fellas and now we are asking people to put us in there – no thanks!”

As Australians ruminate over the results of the referendum, some Aboriginal people believe that a key reason for its failure was the lack of adequate consultation with voters as to what the advisory body would have been responsible for.

In the long run, advocates among Australia’s indigenous population who canvassed for a ‘yes’ result fear that this referendum will be seen by their people as yet another rejection of their rights.

This content is available for subscribers only.